Two months ago, Englewood thirteen-year-old Tamya Fultz sparked a media flurry when she won first place in the Chicago Public Schools’ (CPS) Academic Chess South Conference Playoffs, earning the epithet “Chess Queen of the South” from her math teacher and chess coach, Earle STEM Elementary School’s Joseph Ocol.

Three weeks before that, Tamya placed third in the 2017 Illinois Elementary School Association (IESA) State Chess Finals held in Peoria, where she was the only African American and the only CPS student among the medal winners.

Over the past few years, CPS has made more of an effort to bring chess to its elementary and high school students. Sylvia Nelson Jordan, the coordinator of Academic Teams at CPS, rattled off a laundry list of skills that students learn from chess: analytical skills, strategy, increasing math skills, critical thinking, team building, sportsmanship, problem solving, time management, concentration. And the list goes on.

CPS provides funding for chess programs in schools across the city, giving stipends to chess coaches and organizing free tournaments in association with a nonprofit partner, Renaissance Knights. But for many chess aficionados in Chicago, there is much more work to be done. Over the past few years there has been a resurgence in efforts to provide access to chess for underserved communities across the city. These efforts, spearheaded by individual teachers, librarians, and coaches, have formed a network of small communities revolving around intense gameplay, encouraged by new programs initiated by the city and by nonprofits.

Joseph Ocol’s chess team is one of those efforts. He started out as a math teacher in CPS at Marshall Metropolitan High School in 2005, and he started a chess program there a year later in order to keep his students safer in the hours right after school when there is less parental supervision after one of his students was tragically shot and killed. As Ocol sees it, he’s saving lives. Ocol started another chess program two years ago at Earle STEM after transferring there. The team used to meet Monday through Friday from four to six, but recently cut back to four days a week due to budget cuts.

“My purpose was to save lives, to keep them in school after school. Chess was the least expensive but also the most effective way to develop the critical thinking skills of the kids,” Ocol said. “I really did not expect them to win, but they won again and again.”

Since he started the program, Earle STEM has racked up wins, nationally and across the city. Last year, Earle STEM’s all-girls chess team took home a national championship trophy, and U.S. Representative Danny Davis successfully campaigned to arrange a meeting between some of the chess students and Barack Obama. At tournaments, Earle STEM’s team is often the only one predominantly composed of Black students. Ocol recalled one tournament in which his team attracted stares for being the only Black team in a mostly white tournament. Chess is notoriously a boys club—currently the world’s top 100 players are all men—and boys outnumber girls on the main Earle STEM team. But despite these disparities, Ocol still holds faith in the egalitarian nature of chess.

“Chess does not identify gender. That’s the nice thing about chess. Anyone can play chess, regardless of physical disability, regardless of race, regardless of age,” he said.

Ocol is constantly scrambling to work his way around limited funding. Ocol’s school can’t afford to hire any additional coaches or mentors, so Ocol has his students mentor each other, pairing them up and having students master skills by teaching them to others. Earle STEM often has difficulty paying registration fees to enter its students into tournaments, in addition to transportation and food expenses for lunch. So Ocol comes up with prizes and tournaments of his own within the club, in addition to searching for outside sponsors to help defray tournament costs. Just last week, Southwest Airlines agreed to donate ten round-trip tickets to send team members to the SuperNationals Tournament. But these kinds of special opportunities are not often available to the average CPS team. However, even if free airfare isn’t usually in the cards, CPS and other nonprofit organizations are trying to expand the kind of support available to student clubs across the city.

The Current State of Youth Chess

The Department of Academic Competitions at CPS holds two playoff tournaments a year, one for the North Side and one for the South Side. Sixteen schools participate in each tournament, and around 400 kids play in the tournaments overall. Hundreds of other students make use of chess programs in schools, but don’t participate in tournaments.

Perhaps given in a system in which under one percent of schools participate in district-sponsored tournaments, CPS’s total chess participation numbers remain far below those in other big-city public school systems. New York, for example, has a far more robust chess program. According to the Illinois Chess Association, the city of Chicago has a total of 1,500 chess players from kindergarten up through high school—less than half a percent of the total student population of just under 400,000. New York, on the other hand, has an estimated 23,000 players from Kindergarten to twelfth grade, accounting for around two percent of the student population. Less than ten percent of schools in Chicago have chess programs. In other major cities, that percentage can be over seventy percent.

Jerry Neugarten, a longtime chess coach and founding member of the Chicago Chess Foundation (CCF), a nonprofit chess support organization formed in 2014, attributes the city’s lagging chess performance chiefly to a hundred-year-old CPS policy decision. In the 1920s, chess was put in the Sports Department.

“[Chess] languished there,” Neugarten said.

In 2014, CPS transferred the chess program to the Academic Competitions Department but, according to Neugarten, did not have funds available to significantly expand and restructure the program.

The numbers have improved slightly over the past few years. Interest has gone up as more students participate in tournaments. In 2008, 200 students participated in the North Side playoff tournament and 173 in the South Side playoff tournament. This year, 211 students played in the North Side tournament and 202 in the South Side tournament. These numbers don’t include students who attend club meetings and trainings but do not attend tournaments.

Filling the Gap

CPS introduced a new program in 2013, called First Move, that introduces second and third grade students to chess at an early age. The program is designed so that even teachers who don’t know chess well can still provide instruction through teaching videos. Coaches from the First Move program visit schools occasionally, including the “chess lady” who appears in the videos. According to Darcy Linde, the president of the University of Chicago Chess Team who coaches part time at Cook Elementary in Auburn Gresham, when the chess lady visits, kids “freak out.”

The First Move program is in one hundred CPS schools currently and is expected to expand, according to Nelson, the CPS Academic Teams coordinator. The program is run by a national nonprofit at no cost to either the school or to CPS, Nelson said, and continues to expand its funding and operations in Chicago. But while successful, First Move is limited. It serves a narrow age range of students and can provide basic instruction, but not build competitive teams.

The CCF is trying to fill the void left by decades of lackluster programming by supporting chess teams across the city, especially in low-income schools, through funding, coaches, and teaching resources. There are currently approximately ten small private chess providers in the city of Chicago and one other nonprofit partnered with the city, Renaissance Knights Chess Foundation (RKCF). RKCF provides some free tournaments to students, but charges about $10 per class.

Jerry Neugarten, the CCF board of directors member and the primary author of the CCF curriculum, believes that the current options for Chicago students are far from adequate. He started coaching and playing chess when his son discovered the game at seven years old and demonstrated talent. Neugarten was impressed by research demonstrating the benefits of chess for children; he referred to an avalanche of studies suggesting the positive effects of chess on everything from concentration to Wall Street employment rates. Neugarten coached his son’s chess team in upstate New York and then Highland Park, eventually running the district-wide program. A Hyde Park native himself, Neugarten got involved in the ICA Youth Committee after moving back to Chicago about ten years ago.

“The game is for many kids irresistible to play. But in order to improve, you have to slow down and think about your choices,” Neugarten said.

The CCF currently operates in nineteen schools, distributed roughly evenly across the North, South and West Sides, but recently launched a fundraising effort and hopes to expand to a few hundred more in the next couple of years. Thirteen of those school programs were started by the CCF from scratch as part of their Rook, Rattle, and Roll program, which provides stipends, equipment, and mentoring. CCF’s other major program, Pawns to Queens, takes schools with preexisting strong chess programs and provides advanced instruction. In just the last week, the CCF was able to announce two more programs: an online competitive coach marketplace that aims to bring costs down and bring in more independent coaches, and a “CCF Fellows” program for high-schoolers who can assistant-coach at elementary schools for community service credit.

Chicago Chess Legacies

In the late 1970s, Jules Stein started the original Chicago Chess Center (CCC), which ran in Lincoln Park until he passed away in 1989. During this period, Stein’s center was the focal point of chess in Chicago, situated firmly on the North Side.

Bill Brock is a board member of a five-year-old project to bring back the CCC. The new CCC project is not officially affiliated with the CCF, but according to Brock, the two organizations see each other as working toward complementary goals. The organizers come from the same circles: Brock and Neugarten served together on the ICA before moving on to their current projects.

Brock is also a former president of the ICA and lived in Hyde Park while attending the University of Chicago. He remembers a club on 55th Street and the famous Harper Court chess tables, which were removed in 2002. But other than that, institutionalized chess on the South Side was sparse.

“There were chess players on the South Side. But the South Side was kind of dead,” Brock said.

The most famous coterie of players came from one program in a South Shore public school, Chicago Vocational High School (CVS). Tom Fineberg had been a member of the South Shore Jewish community. While most of that community moved out as part of larger South Side-wide white flight movements in the face of growing African-American presence in the neighborhood, Fineberg stayed behind and worked as a math teacher at CVS, turning it into a chess powerhouse.

“The efforts of one guy really kept chess on the South Side–serious chess-going,” Brock said.

When Harper Court removed its four concrete chess tables without warning in 2002, complaining that the players disrupted business and made crude comments, Fineberg, at that point nearly eighty years old, led a campaign and gathered over 500 signatures on a petition to bring them back. The tables had been a core social gathering point for South Side players since the seventies. Eventually, the two sides reached a compromise. Chess could be played, but on weekends only.

Fineberg taught thousands of students; at any given year his chess team would include as many as one hundred members. One pupil, Emory Tate (who has since passed away), was a five-time Armed Forces chess champion and International Master.

Another star alumnus was Marvin “Uncle Marv” Dandridge, who can still be seen playing at the legendary chess nomads meet-up every Saturday afternoon in a McDonald’s on 95th and Halsted, where they’ve been for the past two years or so. Dandridge is known for prolific smack talk during games, cracking up opponents and spectators alike. Yet another pupil, Daaim Shabazz, now dedicates himself to preserving African diasporic chess history and recently published a book on Tate. On his website, Shabazz claims that highlighting Black chess history will emphasize the universal nature of the game.

Fineberg’s students still dominate the South Side chess scene, but only in the older generation. After Fineberg passed away, no one at his school could pick up the torch.

Islands of Community

Today, as it has been in Chicago for decades now, chess communities are dispersed in small islands all over the city. In the nineties, a lot of the formal chess clubs on the North Side even closed up shop, and the locus of Chicago chess moved out to the suburbs.

“What are the two meccas for chess right now when it’s not the summer time? On the North Side there’s a Starbucks and on the South Side it’s the McDonald’s,” Brock said. “These are the linchpins of the community. That’s how far chess in Chicago has fallen.”

Brock and the new CCC are trying to bring back a sense of centralized community by reinstituting a center in the downtown area, which could serve both South Side and North Side players. But the money to rent a space hasn’t been raised yet. In the meantime, the CCC holds workshops and affordable tournaments all over the city, including two tournaments a month at University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) on the Near West Side. The UIC tournaments attract a diverse array of people, geographically and socioeconomically. The CCF is getting on board as well, and held its first high school tournament in partnership with the CCC in January, also at UIC.

Linde, the UofC Chess Team president, agrees that it’s strange that Chicago chess has no comprehensive organization—as the CCC’s website notes, most large cities in the country have a metropolitan chess organization, but Chicago doesn’t. But the city is so big, Linde argues, that there is little incentive to return to a centralized model when everyone lives so far apart. Neugarten and the CCF run into this problem as well. For their programs on the far South Side, finding coaches can be difficult when most volunteers live in the northern suburbs.

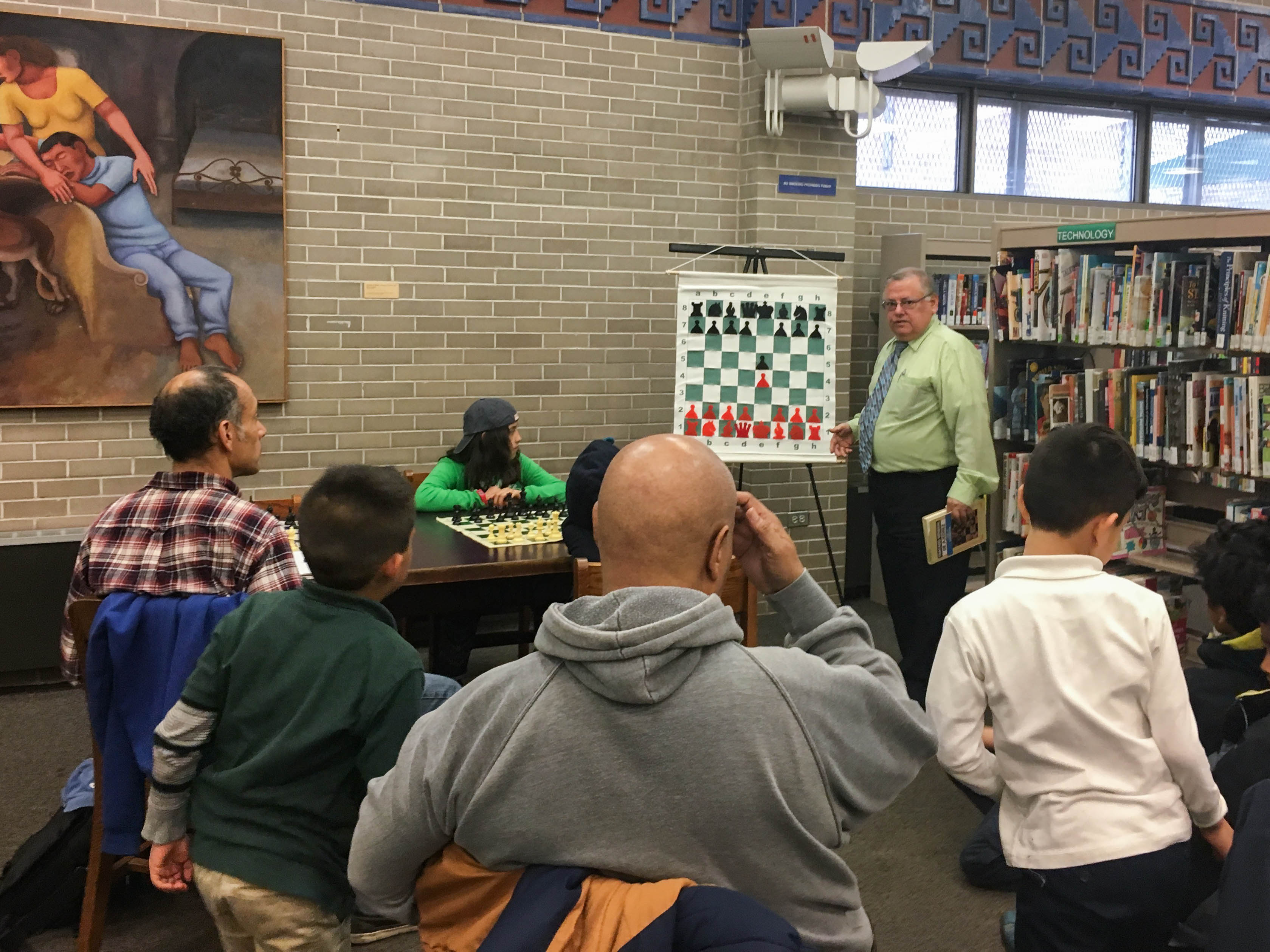

The Knight Moves Chess Club at the Rudy Lozano Branch Library in Pilsen embodies the contradiction of Chicago’s decentralized chess hubs. It remains an island of a community. Héctor Hernández, the coach and branch manager, has been teaching chess in Chicago for over thirty years. He says that sometimes his former students come with their families, bringing the next generation to learn from the same master. Hernández himself was once only thirty-three points away from rating as a Grand Master, but decided to devote himself to teaching instead.

Every Thursday from 6pm to 8pm, a crew of kids, usually in elementary or middle school, file in for a quick free lesson and then an hour and a half of game play. During the lesson, Hernández reviews a match, asking an audience of unusually quiet seven-year-old boys what the best moves are, the definition of a gambit, and how to open up your queen and bishop lines. After each question, lots of eager hands shoot up in the air.

“Oh oh oh, Queen to A4?” “Checkmate?” “No, no, no!”

According to Hernández, a fair number of students come from the surrounding neighborhood, but some trek all the way from distant parts of the city. One father, David Cedeño, brings his son every week from Belmont Gardens on the Northwest Side. Since coming to Knight Moves, Cedeño and his son have started their own chess team at James Monroe Public Elementary School. The team receives funding support through the CCF’s Rook, Rattle, and Roll program. Cedeño is officially the coach of the team, but his son is de facto in charge.

As Cedeño spoke about the new team at Monroe, his son looked up from a game a few tables away, proudly boasting of his teaching role in the team and chastising his father for always opening with the Sicilian Defense. He was referring to a classic set of opening moves where black responds to a white pawn being put forward by putting forward a pawn of its own, out of reach of the enemy.

Cedeño’s son started out playing chess very early on, but recently switched to another school that didn’t have a chess club. After looking around for a new program, they heard about Knight Moves, went to a meeting, and were hooked. “We were able to get him back in the chess community. This is like his chess community now,” Cedeño said.

“It’s like a family,” another parent chimed in. “All the kids know each other since they see each other and play together every week.”

The Lozano Library branch is not simply a space for people to play chess. It’s a community where students can find mentors, learn skills that help them in school, and make friends from all over the city. Chess communities like the one at Lozano are spread out all over the city. South Side chess, in particular, has a strong legacy that city organizations are now trying to maintain with a reliable infrastructure. With new energy and programs in the last few years especially, change is on the horizon.

“You’ve got a lot of heroes on the South Side,” Neugarten said. “A lot of people lean over backwards to get their kids involved in chess.”

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

Emory Tate certainly would have argued the point, but Morris Giles may have been the greatest player born on the South Side.

http://www.thechessdrum.net/blog/2013/01/03/morris-giles-chicago-legend-1953-2012/

(OK, Bobby Fischer was born at Michael Reese in 1943, but we’re not counting him: Brooklyn boy.)

Fantastic article! Thank you, Natalie.

Morris Giles was born in Oakland, CA; Marvin Dandridge was born in Moscow, TN. Emory Tate is the only African-American Master that was actually born in Chicago IL (His family later moved to Indiana).