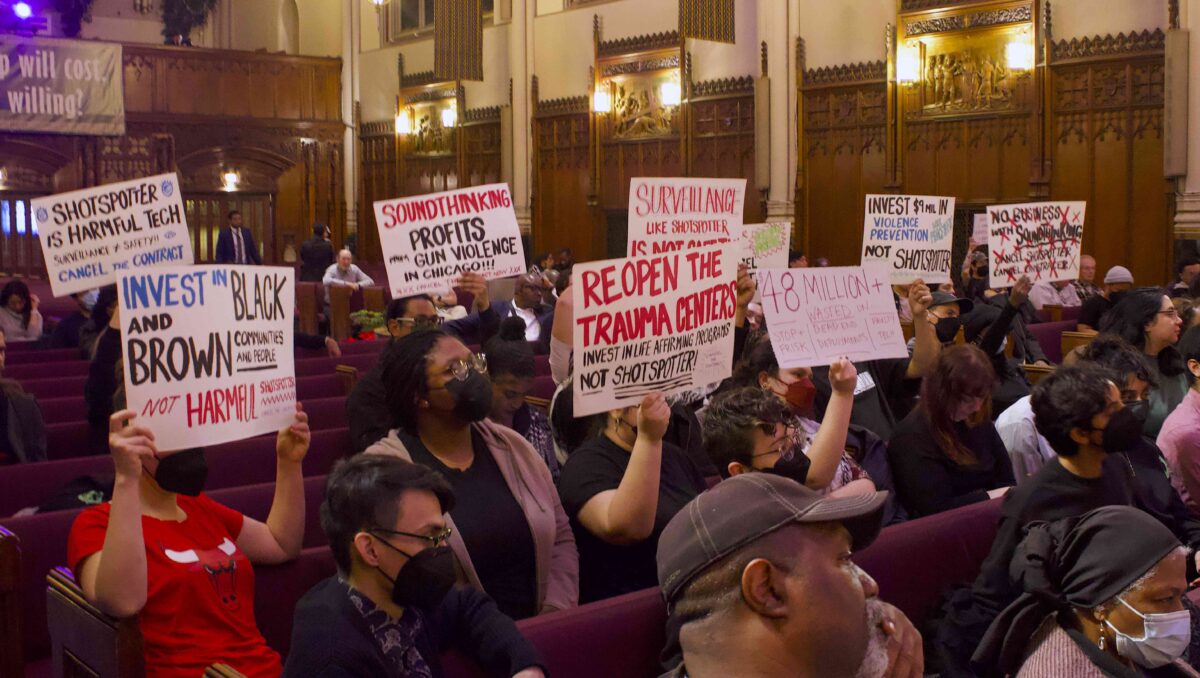

About 150 people gathered at St. Sabina church in Auburn Gresham on Thursday evening for a meeting on the city’s contract with ShotSpotter, the gunshot-detection technology company that has hundreds of listening devices in more than a dozen police districts.

The crowd was a mix of Black, brown, and white people of all ages, and included community members who’d lost family to gun violence, anti-ShotSpotter protesters holding signs calling for the cancellation of the contract, police officers and yellow-vested violence interrupters. By the end of the night, the atmosphere grew tense as opponents and supporters of ShotSpotter shouted one another down.

The Community Commission for Public Safety and Accountability (CCPSA) called the meeting following pressure from organizers of the Stop ShotSpotter campaign, which has been advocating to cancel the contract for years. The contract was initially signed by then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel in 2018, and extended by former Mayor Lori Lightfoot. Its current extension expires on February 16. Mayor Brandon Johnson made reforming policing in Chicago part of his 2023 campaign platform and pledged to cancel ShotSpotter’s contract. Other than explaining why Johnson’s signature was added to a $10 million payment to ShotSpotter in June, the Mayor’s Office has steadfastly refused to discuss the contract since he took office.

On Monday, Johnson met with organizers from the Stop ShotSpotter campaign at their request, but did not provide any updates regarding the contract, according to multiple people who attended that meeting.

Should Johnson decide to renew the contract, the city will have to put out a new request for proposals (RFP), which would kick off a competitive bidding process. There are currently no open bids for an acoustic gunshot detection system, and RPFs typically take weeks or months to evaluate, so there could be a disruption in service if that occurs, according to Block Club.

Sources familiar with the process who spoke to the Weekly on the condition of anonymity said a new RFP for acoustic gunshot-detection technology has already been in the works for some time. Mayoral adviser Jason Lee did not respond to a request for comment, and a spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office did not answer questions about the RFP.

RELATED STORY

CEO Says Johnson’s 2024 Budget Includes ShotSpotter

The CCPSA’s bylaws allow citizens to petition the commission to hold special meetings. Organizers submitted hundreds of signatures, falling just short of the 2,000-signature requirement. But the commissioners decided the petitions, along with calls and emails from community members, warranted the meeting.

“I believe in being responsive to community members, and from everything I was hearing, I knew this was an issue that the [commission] should address,” said CCPSA President Anthony Driver. “We’ve met with countless victims of gun violence. Their voice is not being heard in this debate.”

The CCPSA invited “stakeholders” to the meeting, including ShotSpotter CEO Ralph Clark, CPD 2nd District Deputy Chief Senora Ben, People Educated Against Crime in Englewood leader Darryl Smith, Institute for Nonviolence Chicago Executive Director Teny Gross, and Stop ShotSpotter campaign organizer Nathan Palmer.

Smith and Gross, who lead community-based violence intervention organizations, both said ShotSpotter quickly alerts first responders and members of their own groups to shootings, where they can save victims’ lives or defuse conflicts from further escalating.

During the public comment period of the meeting, Catherine Shaw, an educator and organizer, said that solutions to gun violence should be coming from members of impacted communities, not from for-profit companies. “Continuing to fund death-making institutions—police presence and surveillance—over life-affirming supports perpetuates violence,” she said.

Remis Herrera, who spoke through tears about how she thought her brother’s shooting death in October could’ve been averted had ShotSpotter sensors been installed in the police district in which he was shot. She said ShotSpotter was well worth the $9 million annual cost. “If this technology can save someone’s life, how can we quantify a person’s life?” she asked.

Jose Manuel Almanza Jr., director of advocacy and movement building for Equiticity, called on Clark to release more information about ShotSpotter’s technology functions before continuing to invest in the technology. “If you’re saying it works, prove it,” he said. “Let the OIG [Office of the Inspector General] inspect the algorithm.”

Ald. Silvana Tabares (23rd Ward) spoke in support of keeping ShotSpotter during the public comment period. “The issue of ShotSpotter has become less about public safety and more about political spin.” She added that she had “a problem with outside groups pushing to remove a tool” that reduces officer response times to shooting victims.

The panelists represented a diverse range of perspectives on the efficacy of the technology and its overall impacts. Smith, who has lived in Englewood, a neighborhood wracked by gun violence, for fifty-four years, said that ShotSpotter has significantly helped his community. “I’ve held people in my hands who’ve bled out because the ambulance didn’t get there quick enough,” he said. “I think ShotSpotter is a very necessary tool. If it’s not needed in your neighborhood, good, we’ll remove it from your neighborhood. But in our neighborhood, we need it.”

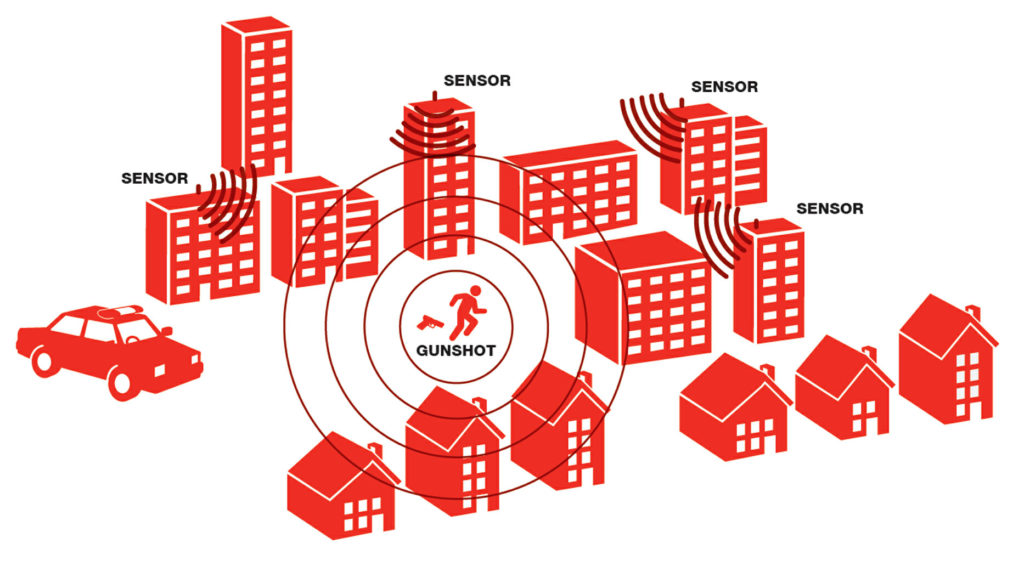

Shotspotter sensors are currently installed in more than half of the city’s twenty-two police districts, including the 7th Police District which covers Englewood. Although primarily located in the South and West Side police districts that experience some of the highest levels of gun violence in the city, the Weekly also identified sensors on the Northwest Side, in Jefferson and Gladstone Park, two sleepy neighborhoods that are home to many cops and firefighters.

Palmer, the Stop ShotSpotter campaign organizer, countered that the company didn’t originally market itself as a life-saving technology. Instead, ShotSpotter initially billed itself as a policing tool designed to apprehend shooters and collect evidence of gun crimes, they said.

“It wasn’t until the campaign in Chicago and campaigns nationally started calling out that police are stopping and frisking our people and falsely incarcerating our people” that the company changed its tune, Palmer said.

In a memo first reported on by the Sun-Times, State’s Attorney Kim Foxx said that the technology is “an expensive tool” that hasn’t taken “trigger pullers” off the street. Her office found that Shotspotter led to arrests in only one percent of 12,000 shooting incidents recorded from August 2018 to August 2023, and that many ShotSpotter-related arrests aren’t tied to firearms.

CPD deputy chief Ben said that ShotSpotter was an important tool in the department’s arsenal. Noé Flores, the assistant director of the department’s Strategic Initiatives Division, said that since 2020 CPD officers have provided life-saving care to more than 400 shooting victims after receiving a ShotSpotter alert. (The number is considerably higher for the number of shooting victims who get care after a 9-1-1 call, Flores conceded.)

“I have concerns about surveillance, I have concerns about if it’s used in court cases,” said Gross, the community-based violence intervention leader. But “it is helpful if there’s conflicts that we’re not aware of…It’s not perfect…we mainly want to rely on relationships, but this is another tool.”

Inspector General Deborah Witzburg answered questions from the commissioners about her office’s 2021 report, which found that less than ten percent of ShotSpotter alerts were associated with any evidence of a gun-related crime. “Public policy decisions and proper resource allocation decisions should be made in a well-informed, data-driven way which captures the experience of Chicagoans,” she said. “The data we analyzed did not demonstrate an operational benefit of the use of ShotSpotter.”

Driver asked Clark about the Weekly’s recent investigation that found CPD emails showed ShotSpotter missed more than 550 reported gunfire incidents in 2023.

“ShotSpotter is not a perfect technology,” Clark conceded. “We are going to produce false positives and false negatives.”

False positives refer to ShotSpotter alerts that are not gunfire. False negatives refer to instances where ShotSpotter’s sensors failed to detect actual gunfire. Clark asserted, however, that the company was fulfilling its contractual obligation of at least 90 percent accuracy, lest it face steep financial penalties.

“I’m really happy to see that our customers are holding us to account for those misses, [and that] we’re operating at 97 percent,” he said.

Toward the end of the meeting, CCPSA commissioner Yvette Loizon spoke at length about ShotSpotter until she was interrupted by members of the crowd. About half a dozen Police District Council members in the audience walked out after 12th District Council member Leonardo Quintero called the panelists’ comments “copaganda.”

In an interview the next morning, Quintero said he felt the panel was biased toward keeping ShotSpotter. He added that it was important to demonstrate that not all Police District Council members were in agreement with CCPSA commissioners about ShotSpotter. “I wanted to make it very known to the Chicago community at large that we as [District Councilors] were not approving of what was going on.”

As the District Council members walked out of the nave and people in the audience traded shouts, Driver took to the microphone to admonish attendees to be respectful and shouted for decorum.

In an interview Friday, Driver said District Council members had the right to protest, but he rejected the charge that the panel was biased. “The Commission did not take a stance; we did not vote,” he said. “That was a panel to try to understand and get to the bottom of [these] issues…. Every person who was on that panel was somebody who had a different perspective.”

Driver added that ShotSpotter is not a binary issue. “The same way there were activists who came to that meeting to express their frustration, there are people by the dozens who reached out to myself and the Commission,” he said.

Multiple audience members interviewed by the Weekly after the meeting said that they felt better informed. Michael Harrington, a lifelong Chicagoan who was in attendance, said it was still important, though, to get more facts.

“I think this was the beginning of some airing of these issues in a good way,” he said. “I really would trust the OIG to get to the bottom of some of this because there’s good arguments on both sides.”

Max Blaisdell is a fellow with the Invisible Institute and a staff writer for the Hyde Park Herald. Jim Daley is the Weekly’s investigations editor.

While there are legitimate concerns about SpotSpotter, anyone who wants to end SpotSpotter because it leads to “over policing of minority communities” needs to realize this is a flawed argument.

Follow the statistics. It makes perfect sense to install the system in neighborhoods with the highest rate of gun incidents because they’re the most likely areas to have it occur again. And if it happens to mostly be in neighborhoods of color, so be it.

Miles, stop making sense!