This story was originally published by the Chicago Reader on December 21, 2022. Reprinted with permission.

The Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland, California, in 1966 by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale as a revolutionary organization that could effectively respond to the racial violence inflicted upon Black Americans by police and society. At that time, many young, Black organizers were becoming disillusioned with Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy of nonviolence, including those who would eventually establish the Illinois Black Panther Party Chapter in 1968: Fred Hampton, who had been a member of the NAACP in high school, and Bobby Rush, who was initially a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

The Black Panthers advocated for freedom from oppression by any means necessary, including armed self-defense. Political education was central to their initiatives. Panthers created many survival programs such as the Free Breakfast Program, the influence of which can be seen on the USDA’s national School Breakfast Program and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program. At its peak, the Panthers’ Free Breakfast Program in Chicago served 4,000 kids every day.

The survival programs were named as such because they were designed to help the Black community to survive until a revolution, which Panthers anticipated, radically changed the unequal arrangement of society. Social programs also served as the basis of the Party’s organizing activity and service to the public. The Illinois Chapter was organized by August 1968—with Hampton as deputy chairman and Rush as the deputy minister of defense—and recruited at schools and universities.

Unlike some other revolutionary Black nationalist groups at the time, the Panthers organized alongside non-Black radical groups who were fighting the same issues of police brutality, poverty, and poor housing conditions. In Illinois, Chairman Hampton eschewed segregation lines in Chicago and successfully created the Rainbow Coalition, which allied Chicanos, Puerto Ricans, and Appalachian whites.

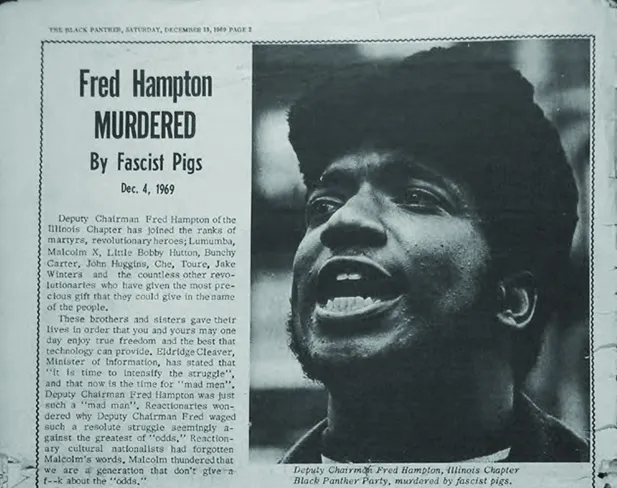

All the while, national media organizations spread incendiary images of armed Black Americans and attributed other groups’ violence to the Panthers in an attempt to discredit them. The FBI and Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office coordinated to infiltrate the group with informants. This culminated in the assassination Fred Hampton by Chicago police on December 4, 1969.

Last month, five members of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panthers discussed their experiences in the Party with the Reader. Samuel Latson joined at eighteen and served as a field lieutenant who would roam the streets and educate people about the Party. Wanda Ross also joined at eighteen and was a key organizer of the Breakfast Program. John “Oppressed” Preston joined the Party at fourteen, and worked with a cadre responsible for distributing the Party’s newspaper. Billy “Che” Brooks joined at twenty and served as the chapter’s deputy minister of education. Ann Campbell Kendrick joined the party at twenty and served as acting communications secretary.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Joining the Party

[W]anda Ross: I was eighteen. It was my first year of college on Circle Campus, which today is UIC, and that was when I was exposed to a lot of groups. I heard Fred speak there, and I was impressed. We went by the office, and we were blown away.

The thing about the Panthers is that between eighteen and twenty-five we were very sure we were going to change the world. King getting killed was kind of the last straw. I remember as a kid watching them use the dogs and turning the hoses on to attack the marchers. I’ll never forget crying and jumping up and down because I was still in high school, and I couldn’t go down south on the freedom marches. And you look at people who came back, they came back bruised; some of them had been in the hospital because they’d been beaten up.

And then you said, “Wait a minute, we’re just regular people, we’re trying to go vote, but it’s in our lifetime that we are seeing a change coming.” After Martin Luther King got killed, we needed to speed the process of freedom up. The Panthers were part of a perfect storm of the protests of the times. And King’s assassination was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

John “Oppressed” Preston: And that was the thing: you began to understand a whole lot of things about the country itself. We experienced a lot of containment in our own communities in terms of the mobility of people from the Black community. We couldn’t move around as a regular community. When the [King assassination] riots came, the people that lived in that parameter couldn’t leave up out of that parameter. The National Guard were there, the National Guard were along every bridge along the expressway. And then we couldn’t go past Madison Street. And then in terms of other people that didn’t live in public housing, you still couldn’t move around because you were subjected to the seven o’clock curfew. If you were driving in a car, your car was subject to search. And the level of police brutality that was there too.

Samuel Latson: I was eighteen when I joined the Party. I ended up as a field lieutenant. My role was to go out into the community and let the people know about the Black Panther Party. There were a lot of misconceptions about the Party in the beginning. We sold newspapers, we talked to people, and we organized. Those that were interested would come to the office and get recruited. I had to keep tabs on what was going on in the community, as far as violence, police violence, police brutality, or any other thing we knew we might be able to help people with. At first my area encompassed the south side.

As far as what I’m doing now, I am a bona fide Christian. I am very involved with the church. I do outreach, I go to the prisons, I go to the nursing homes, I go out in the community. And basically where there’s a need that I’m aware of, I try to meet that need where the people are at.

Ann Campbell Kendrick: When I came into the Party, I was twenty years old; I was beginning my sophomore year at Chicago Teachers College at 69th and Stewart, and I met Bobby Rush and Billy “Che” Brooks. They were attending Wilson Junior College, which was right down the street.

Before the Party, a lot of us were involved in the Black Power movement. I think King’s assassination was the straw that broke the camel’s back; we had lost Malcolm, there were a lot of things going on. And it was like, “OK, what else can we do at this point?” We thought that some of the nonviolent approaches weren’t effective or working for us. So we got word that a chapter of the Black Panther Party was forming. They even had a few meetings at our house.

My mother, known as Mama Jewel, was very supportive of the Black Panther Party and the things that we did, unlike so many parents of Panthers. A lot of people got put out of their houses once the parents found out that they were a part of this revolutionary organization, which was another reason why we needed to have a Panther crib to go to.

When I joined the Party, I joined as a rank-and-file member. Iris Shin was our first communications secretary. When she left I became the acting communications secretary. We were responsible for doing reports weekly; maintaining the files and records in the office, answering phones, setting up press conferences, scheduling speaking engagements for the leadership. We did everything that we were asked to do. I worked in the breakfast program and at the medical center. I had to make calls and contacts with different medical supply companies trying to get supplies and things donated. We had a press conference, and Fred was telling me different things to point out about the medical center during the press conference. I also worked for the People’s Law Office because we did not have funds to pay the lawyers. As we grew and developed, so did the charges and the arrests and the harassment from the police, so the cost for legal fees mounted. So I would go to the People’s Law Office and work some of that off.

I was at the Party for about two years. I had to work and go back to school. Maybe a year later, I got married and had a son. I did go back to school and got my degree in education. I taught in the Chicago Public Schools for thirty-four years. I retired in 2009. And even though I was not active in any particular organization, I always did what I could do to make my students in the classroom aware of, you know, some of the injustices and certain conditions.

But I can say that my relationships with my comrades have outlived some of the relationships that I had with other people. I’ve known these people for over fifty years, these comrades, my brothers and my sister. And that’s something that no one can take away from: the experiences that we managed to live through. We survived.

Preston: And we’ve lost a lot of them along the way.

Political Education

Preston: There was a whole cadre that was responsible for distributing the paper throughout the midwest. I became one of the circulation managers. I was responsible for getting the paper printed here in Chicago and shipping the paper around the country as well as distributing it. At that time, the same printer that printed our paper in Chicago was also printing the Reader. It was a company called Newsweb, owned by Fred Eychaner.

There was also a Heidelberg press that belonged to Students for a Democratic Society. They printed our weekly newsletters. They were about eight blocks down from where our office was. There were factions within SDS: the Revolutionary Youth Movement, the Weather Underground, and then there was another faction as well [Editor’s note: the third faction was called Progressive Labor]. And the Weather Underground was the one that actually owned that press, so once they went underground, we were able to acquire that press.

We started off with, you know, printing stuff with a stencil, with mimeograph machines, you know, writing stuff out and we were able to do flyers and then we were able to acquire a multi-lift press where we could print like eight and a half by eleven inch flyers and things like that. And that was all done by the Ministry of Information. So the distribution and information part was done through that particular ministry.

Articles came from chapters and branches all over the country. A lot of the design was done through the Ministry of Culture. Emory Douglas was responsible for designing the paper. The information cadre would print the paper or choose what articles went into the paper that week. As the circulation department, we were responsible for not just the paper but for all of the literature that the Party produced: buttons, books, albums. I was responsible for going around the country, doing events, setting up events, and things of that sort. So I was young, but I got a lot of training from a lot of older brothers in the Party. I wasn’t some kid whiz junior genius. I was just a normal cat.

Sam Napier was our national circulation manager. We also had a national distribution manager by the name of Andrew Austin. So I served as a part of their cadre, and it was a very, very vital cadre. Napier was assassinated during the Party’s schism in 1971.

Have we made some strides and accomplishments? Yes. But the struggle has not ended. The struggle is ongoing. Period. And it’s going down from generation to generation. When I joined the Party, I thought that we were gonna overthrow the government and make change in about a year, and then everybody’s going home. And, of course, that was my childish idealism. The child in me is still there, but you have to evolve and understand what these conditions are and go back into history as well.

Billy “Che” Brooks: I was the deputy minister of education for the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party. I joined the Party when I was twenty years old in 1968. I was a student at the time at Wilson Junior College. The first time I went to jail, it was for participating in a tent-in demonstration against slumlords on Roosevelt and Pulaski, where I met Doug Andrews with the West Side Organization, and Fats Crawford with the Negro Rifle Association. I didn’t get fully engaged in the struggle until ’68. April 4 was a critical point. The assassination of Martin Luther King had an impact on the entire city. The entire community was in an uproar.

And as deputy minister of education, my role was to ensure that all Party members knew and understood the Ten-Point Program and Platform, which was more like a survival kit because it was the creation of sociali-stic programs within a framework that we utilized to organize people and empower people. It was a socialist framework: each according to their ability, each according to their needs. As an educational tool all ten points were taught. We were Marxist, Maoist, in that framework, trying to understand how to deal with solutions to concrete problems. As Huey [Newton] used to say, you know, that in order to understand, you got to do work, social practice, you know what I’m saying? That was how we developed our programs, but our ideology and philosophical understanding was manifested in the Ten-Point Program, and it was important that Party members understood that. Every issue of the newspaper had a particular lesson that we would process. But most of the political education classes were taught by comrades who were in the cadre, you know, because I was in jail a lot.

Survival Programs

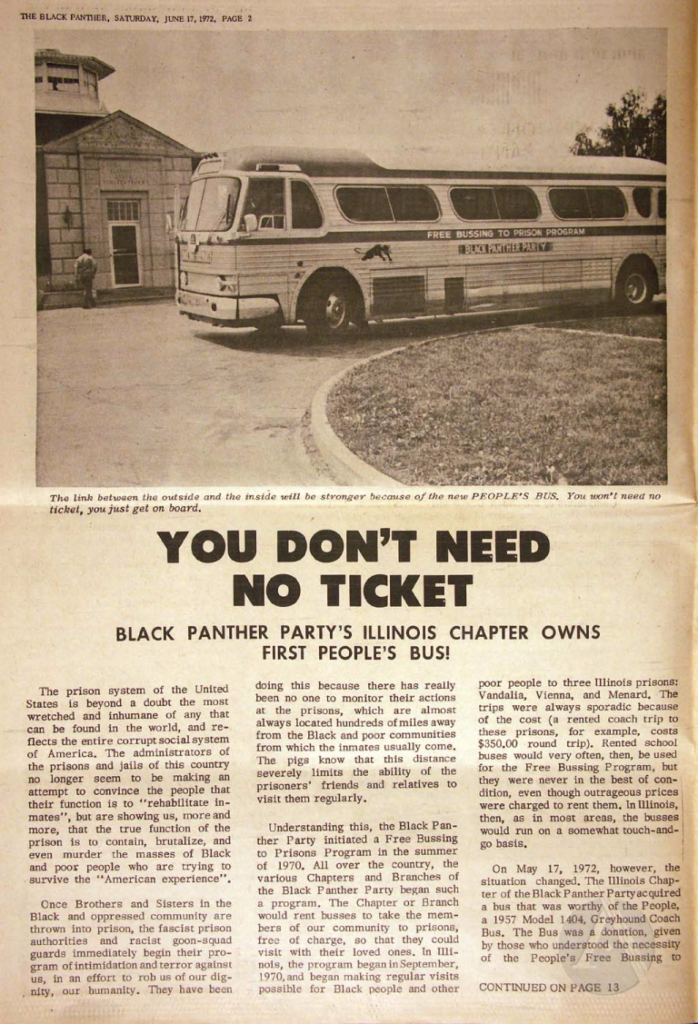

Brooks: The point [of the survival programs] was to increase people’s conscious awareness of the type of things that needed to be done. We did this with the breakfast program, the medical center. All in all, we had over fifty survival programs: a free prison busing program, a free clothing program, and a free ambulance service. And if you look at the ten points of our platform, you’ll see the actual program emanated out of each one. We prided ourselves on being dialectical materialists, in terms of being able to look at the problem and actually come up with something that we could do to impact the problem. We put things into practice. We truly believed that social practice was the criteria for truth.

Ross: I was in charge of the Free Breakfast Program. In most situations, I very seldom took money. Most of the time, I preferred to take the product. So, I’d get ninety dozen eggs once a week. I did not want to handle much money, and I didn’t want people to feel that we were soliciting for pocket money. We needed food; I would just go pick it up. Sometimes, if someone wanted to donate money, I would have them write a check to whoever we were picking stuff up from. We didn’t have a menu; we just cooked breakfast, which was sausage, grits, eggs, toast, and sometimes oatmeal. The Panthers would get to the site by 6am and start cooking. We would be open by 7am.

Latson: We didn’t realize that our programs were more of a threat to the system than talking about guns, because we were actually stepping out there meeting the needs of the people. People were afraid of us because of the guns. But the social programs that we set up, [the state] co-opted. They destroyed the Party, basically, and co-opted its programs because we raised the consciousness of the people as far as the services that the Black community was not getting.

The Role of Women in the Party

Brooks: The Black woman has always been in the forefront, has always been the bodacious ones, going all the way back to Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. I would say the role that the sisters played in [the Illinois] chapter enhanced every possible program that we had. The role that they played was critical in leadership. And we didn’t really process male chauvinism and sexism to a point where it became a concern. Initially it was. But Chairman Fred made it very clear that that was not something that we were gonna be processing here. You know, that’s a fact.

Ross: We still had to deal with the larger society that we came from. So yeah, there were Panthers that were chauvinist. But at the same time, the type of doctrine that we tried to incorporate was: “this is an issue that we all need to deal with, if we’re going to be better people.” And the Black male population has been controlled either through war or through jail. And over the past thirty years, the amount of Black men in jail away from the community also breaks up the family structure, you know, and obviously, there must not have been a war that could take enough Black men off the street. But it’s something to realize that you’ve got a whole generation of young people 30 and under that had, and have been in jail.

The Rainbow Coalition

Preston: You know, a lot of times the Party evolved, and we evolved from the basis of Afrocentrism to understanding what the struggle is. And that’s why a lot of programs and a lot of initiatives that we came up with—particularly the Rainbow Coalition—was to expose and to educate people as well and to bring people into the fold. But these were things that Dr. King was doing all along when he was organizing. These, you know, these are things that Malcolm saw [when he came back from Mecca], so we all began to evolve into these things. And so we created that when we created that first original Rainbow Coalition, saying, “Hey, you got poor Hispanics, poor white folks, you got poor Black folks, and our struggle is the same.”

The Party and its ideals will endure through the ages. We’re not going to make no mistake about that. Sometimes I sort of get a little perturbed because when you speak to people nowadays, they speak about the Party in a historical or past tense. And that’s not the case. You know, I still consider myself a member of the Black Panther Party. I’m still a Party member; I’m not a former member. I’m still a current member. We have to understand that these conditions still exist. The Ten-Point Platform and Program is still as relevant today as it was when it was written. Because the conditions haven’t changed.

Brooks: The Rainbow Coalition came together because we had the same problems: housing, police brutality. That was the focal point that created the opportunity to have a conversation, in particular with the Appalachian community. At that time, Puerto Ricans were being pushed out of Lincoln Park. We had the Contract Buyers League and the whole redlining concept in Englewood, North Lawndale, East Garfield, West Garfield.

Chairman Fred had that innate ability to bring people together, and the commonality that we had was the housing situation, the police brutality situation. They bought into our Ten-Point Platform and Program, particularly the Young Lords. So it’s all about solidarity. It’s all about understanding the commonality of our concerns and our problems. In 1970, when most organizations didn’t know anything about gay rights or the women’s rights movement, the Black Panther Party supported the gay rights movement, supported the women’s liberation movement. Huey always talked about the importance of allies. We need allies in this process, so that was the conceptual framework of the Rainbow Coalition.

It’s needed today, more so than ever. The whole push of white supremacy and privilege, which is manifested in this whole case up before the Supreme Court right now, where a state has the right to define what gerrymandering is. These were issues we fought then, and we were effective at fighting these issues because we were organized. There was a movement back in the day that processed the entirety of the situation, not single-issue things. And people came together in a collective, in a communal form and fashion, you know, because it was a worldview. We gravitated from Black Panther Party for Self Defense to revolutionary intercommunalism: looking at poor and oppressed communities around the world, and whenever one of those communities gains their freedom, it helps us.

Latson: The system is never going to change. It’s based on, as Malcolm said, exploitation. White folks don’t want to give up their power under any circumstance. We’re getting to this point, as far as I’m concerned, where they’re trying to take us back. Now, if the masses of the people continue to allow this to happen, then we will go back. It’s in the people’s hands. But the system is not going to change. This struggle is gonna go on and on and on until people make up their minds that they don’t want to accept it. We, as a people, don’t understand politics, the political end of the system, how it functions. The masses of the people don’t understand.

Debbie-Marie Brown is a staff writer at the Chicago Reader.

First I want to thank you all for voices to justly be heard. This is important history for this generation too know from the horses mouth!!! You are right allies is important in the same commonalities to us all, people is power!!! God is moving things all around the lands, the peoples no one or on thing is ever above god!!! God wants all this people free not divided!!! They want to send anyone back they best start with themselves everyone is an alien from all the generations!!! See what we have that they don’t have is God and Jesus as our lord and savior. God is love and loves us all!!! Change is going to come they like it or not. “The child will lead the lion!!!”