On Monday, the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Institute for Research on Race & Public Policy (IRRPP) released “A Tale of Three Cities: The State of Racial Justice in Chicago Report,” a study that analyzes disparities in housing, economics, education, justice, and health between Black, Latinx, and white communities in Chicago. Using robust quantitative evidence from a variety of sources, each section delves deep into the history, causes, and consequences of these racial and ethnic inequities that “remain pervasive, persistent, and consequential” in Chicago’s institutions and neighborhoods.”

According to Kasey Henricks, one of the authors and a postdoctoral associate at the IRRPP, the report is unique in how it addresses the intersections of inequalities in different areas of life.

“If you’re talking about race, it doesn’t operate in a silo or a vacuum,” said Henricks. “It’s systemic. You can’t talk about race in one area. You have to include institutions and dimensions because they’re overlapping and you need to talk about them all at once.”

Here, we highlight conclusions from three of the sections in the report—the economy, housing, and education.

ECONOMY

As part of the section on economics in the “State of Racial Justice,” the report’s authors trace the effects of “economic restructuring” on Black, Latinx, and white populations in the city. They note that Latinx workers have been most drastically affected by the shift away from manufacturing: in 1960, fifty-six percent of Latinxs workers were in manufacturing; by 2015, that number was down to just over sixteen percent. And while jobs for white workers have tended to move toward professional occupations and high-end service jobs—think doctors, lawyers, or tech workers—Black and Latinx people have increasingly been shunted toward retail and low-end service employment.

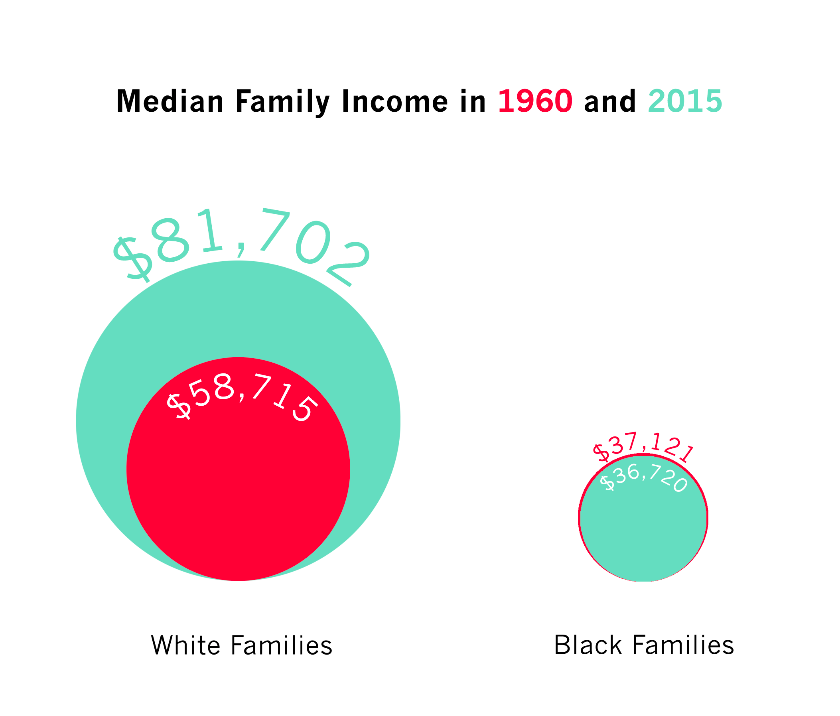

One corresponding effect is that Chicago’s white families have seen a generous rise in their median incomes since 1960, from $59,000 to $82,000, while the median income for Black families has effectively remained the same: about $37,000. (The median income for Latinx families has also gone up, though not nearly as dramatically as for white families.) But the report emphasizes that income inequality isn’t simply due to differences in location or educational levels: instead, there is an underlying inequality that can be attributed to race. For example, Black men make twenty-two percent less than white men after all other factors are accounted for. In other words, people of different races experience different economic outcomes.

The report traces this racial inequality across different measures and sectors. While higher levels of education tend to help alleviate unemployment and increase income among Black and Latinx Chicagoans, both groups still lag behind whites with the same degree, and sometimes behind whites with fewer years spent in school. The report also shows that most Black and Latinx wealth is in the homes they own, as opposed to more “liquid” assets more, like stocks and bonds—which can be converted more quickly to cash. One tragic effect of this difference was that the real estate crash, which kicked off the Great Recession, further exacerbated race-based disparities in wealth; around 2009, “the typical white household had just about $20 of net worth for every $1 held by the typical Black or Latinx household.”

In a commentary on the section, Teresa Córdova, Director of the Great Cities Institute and a professor of urban planning and policy at UIC, gives some context to the bleak picture painted by the report, noting that deindustrialization in Chicago went hand-in-hand with social service cuts, disinvestment in minority neighborhoods, and an increasingly harsh criminal justice system. Alongside these worrying trends is a tougher one: as economic output has grown over the past several decades, profits tend to end up with an already-rich, mostly white upper class. But Córdova also sees some cause for optimism, arguing that there are plenty of jobs available in advanced manufacturing—the parts of manufacturing that are high-skill, and aren’t immediately at risk of automation or outsourcing. “Manufacturing in the region has changed, but it is not dead and can provide a viable avenue for rewarding and lucrative employment for Blacks and Latinxs seeking opportunities in this sector,” she writes. “Education, though it does not erase disparities based on race…does improve the possibilities and opportunities for advancement and is worthy of public commitment and investment.”

HOUSING

According to Kasey Henricks, Chicago’s history of segregation has long been the foundation for the multitude of issues facing Chicagoans today. The housing section of the report argues that segregation not only disproportionately affects communities of color but also “costs lives, income, and potential” all across the city.

Chicagoans have long been subject to decades of legally defensible racist housing policies and practices. After the Great Depression, homeownership became more affordable through New Deal programs, but many of these programs severely underserved Black residents, which systematically prevented them from buying homes. Combined with the practice of “redlining,” in which racist criteria marked property in majority-Black neighborhoods as “undesirable,” the narrative that Black residents lower property values continues to fester. Although the 1968 Fair Housing Act technically prohibited racial discrimination in any housing-related transactions, a slew of loopholes and newer, more insidious tactics of segregation have made equitable homeownership nearly impossible for Black and Latinx Chicagoans. The report argues that housing discrimination now takes the form of a two-tier subprime lending market, in which “minority borrowers in predominantly minority communities [are subjected] to unconventional loans” that come with predatory fees, interest rates, and penalties. Because of these subprime mortgages, the majority of Black and Latinx homeowners are cost-burdened, compared to only 35.7 percent of white homeowners, and spend thirty percent or more of their household income on owner costs.

This devaluation of Black-owned property set the stage for Chicago’s twenty-point gap in homeownership between Black and white Chicagoans and the rapid depreciation of homes in majority-Black communities. After the housing market crisis nearly a decade ago, the report’s authors observe that most of the foreclosures occurred in several minority communities in the South and West Sides such as Austin, Belmont Cragin, and West Lawn. The concentration of these foreclosures leaves “large portions of neighborhoods being left abandoned,” which the authors argue leads to “community deterioration,” the decline in values of surrounding homes, and the increase of “zombie properties,” which are foreclosure claims that have not been resolved in three years.

One of the most prominent conclusions about housing segregation in Chicago is that according to the 2010 Census data, Chicago has remained for decades one of the most segregated cities in the United States. The authors note that “while some black Chicagoans reside in predominantly white neighborhoods, virtually no white Chicagoans live in Black neighborhoods.” Using a tool called the dissimilarity index, which measures how evenly Black and white populations are spread across a city (0 indicates total integration, 100 indicates complete segregation), Chicago scored an 82.5 between Black and white communities. While this number dramatically decreased from 1980, when the score was 90.6, social scientists still posit that any score over 60 is indicative of very high levels of segregation.

Furthermore, the report pushes back against the idea that segregation in Chicago was an inevitable consequence of market forces – what the authors call the “‘it’s really economics’ idea.” Proponents of this idea claim that if people of color had the same access to resources as white people, they would occupy the same neighborhoods that whites do, and “segregation levels would decline as income levels rise.” While the authors found that this holds somewhat true for Latinx households, segregation persists within Black communities despite increases in income. Essentially, “affluent Black households are almost as likely as poor ones to be segregated from whites.”

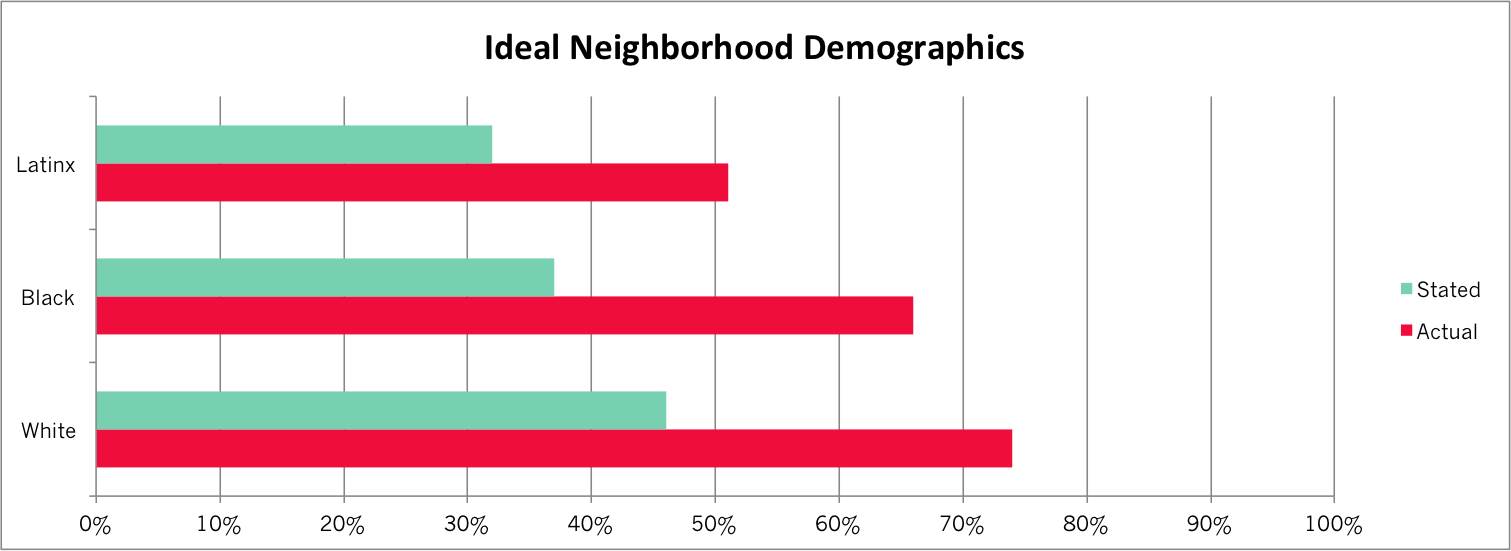

The authors also point out the contradiction in white Chicagoans’ desiring a residence in diverse neighborhoods yet consistently ending up living in a neighborhood that is majority-white. According to a study cited in the report, on average, white home-seekers said that they wanted a neighborhood that is forty-six percent white, but ultimately moved into neighborhoods that were seventy-four percent white. Black and Latinx residents, on the other hand, wanted a neighborhood that is thirty-seven percent Black and thirty-two percent Latinx respectively, but ended up living in neighborhoods that are sixty-six percent Black or fifty-one percent Latinx.

Ultimately, the authors of the housing section in the State of Racial Justice Report note that even though housing discrimination in Chicago is technically illegal, discrimination—and its consequences—have yet to disappear.

EDUCATION

With a long-suffering budget and tumultuous overturns in leadership, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) has been embroiled in decades of political and economic conflict. Now, even though CPS is a “majority minority” school district that serves mostly students of color, the State of Racial Justice Report shows that students in CPS may be more segregated in their schools than in their own neighborhoods. And despite the changing demographics of CPS, minority students are now more unlikely to be taught by a teacher of the same race. Compared to a decade ago, “when one out of every three CPS teachers was Black,” now Black teachers only make up one out of every five teachers. The authors argue that this decrease in Black CPS teachers can be attributed to disproportionate layoffs; Black teachers were forty percent of all layoffs in 2011, fifty-one percent of all layoffs in 2012, and twenty nine percent of all layoffs in 2015.

Perhaps this disparity in teacher representation is connected to how Black and Latinx students are more likely to receive harsh disciplinary punishment than white students. According to the 2015-2016 school report, “Black students were suspended at double the district rate…nearly four times the rate of Latinxs, and ten times the rate of whites.” Black students were also 76.9 percent of all expulsions, which is four times the rate of Latinx students and twenty-three times the rate of white students. When Black and Latinx youth are already “disproportionately processed through the state’s juvenile justice system,” these inequalities in punishment in CPS is evidence of the racial presumptions behind notions of innocence and guilt, and who deserves rehabilitation and who deserves punishment.

The report extends the definition of segregation to not only racial divisions but also the educational consequences of class inequalities. High-poverty schools are often in majority Black and Latinx neighborhoods and often employ less experienced and less qualified teachers, experience high levels of teacher turnover, and lack effective peer groups, facilities, and learning materials. These schools are also unable to offer robust programming such as gifted and advanced academic programs and arts programs so that “Black students are nearly seven times more likely than other groups to attend a school that offers neither arts nor music.”

Furthermore, the report shows that CPS has long been plagued with school closings, as more than 250 public schools have closed from 1980 to 2015. Most of this closure activity has transpired in recent years. Many of the closed schools were ones in the South and West Sides, and in 2013, thirty-five of the forty-three schools closed were in neighborhoods with majority-Black or Latinx residents. These shuttered schools mostly have not been repurposed for other public services but instead reopened as charter schools, or left barren.

Ultimately, the authors argue that the medley of educational disparities across CPS has led to “persistent racial disparities,” such as wide achievement gaps in between Black, Latinx, and white students in standardized test performance. While the authors note that CPS’ graduation rates have nearly doubled over two decades, there are still significant gaps in graduation rates between racial groups. Only six percent of Black men, eleven percent of Latinos, and thirteen percent of Black women from CPS receive a college degree ten years after entering high school. Compared to the twenty-seven percent of white male CPS graduates and thirty-six percent of white female CPS graduates that accomplish the same feat, Black and Latinx students in CPS are now less likely to receive the employment and income benefits that a college degree often brings.

At the endnote, Pauline Lipman, a professor of Educational Policy Studies and Director of the Collaborative for Equity and Justice in Education at UIC, writes that systemic inequality in CPS has long been challenged by activists, families, and students. From the boycotts, walkouts, and grassroots protests against school segregation, racist curricula, and the notorious Daley-era Willis Wagons, Chicago’s communities of color have been continuously fighting for equity for their students. Now, the battle involves resisting the closing of schools that acted as multigenerational community institutions, the redirection of public funds from neighborhood schools to selective enrollment and privately-run charter schools, and a historically mayor-appointed school board.

“But the racial injustice of these policies cannot be fully conveyed by [quantitative] measures,” Lipman concludes. “Numbers can only hint at the human costs of diminished education and life opportunities, loss of committed teachers (particularly Black teachers), trauma of criminalization, and the culture of punishment and shaming visited on primarily Black schools, teachers, students, and their communities. Nor do they capture the social costs and collective trauma to families and communities of shuttering public schools that were community anchors.”

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

Thank you for exposing this. We still have to overcome Jim Crow.

Excellent commentary! A message that must be widely disseminated. Thank you for your work. I will pass this message on.