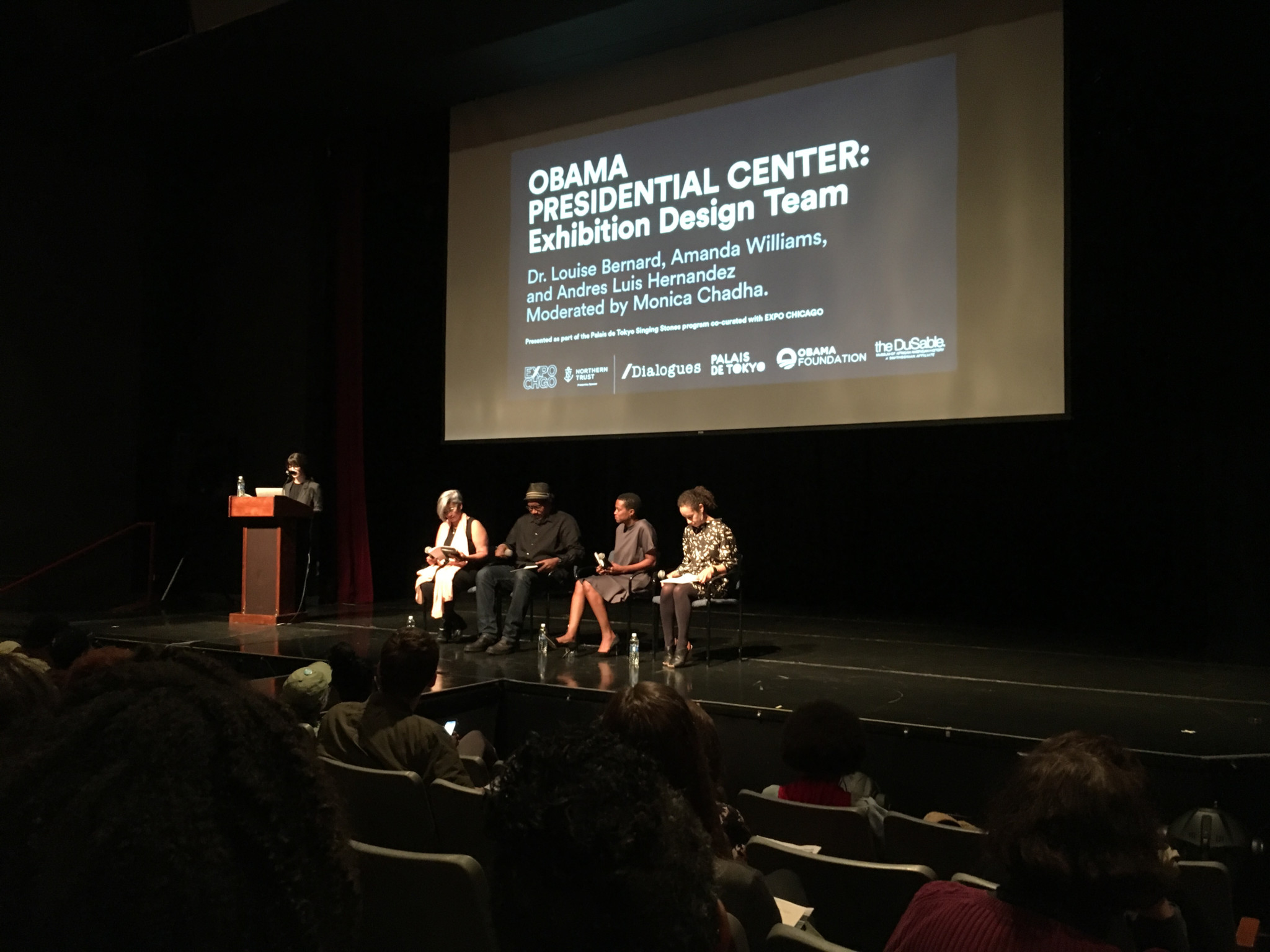

On Saturday, October 14, rain poured down in torrents, the air cold and dark. It was one of the first chilly, rainy days after two weeks of unusually warm early October weather. Yet dozens of people made it through the storm to the DuSable Museum of African American History for EXPO CHICAGO’s panel conversation introducing the design team behind the Obama Presidential Center (OPC). In a shift from the typically fraught conversations about the OPC’s economic and local community impact, the panel instead focused on illustrating the design process behind the OPC, and discussing its role as an innovative social and cultural institution.

On the panel were Louise Bernard, the Director of the OPC, as well as Amanda Williams and Andres Luis Hernandez, artists and members of the OPC’s Exhibition Design Team. Moderating the event was Monica Chadha, founder of Civic Projects and another member of the Exhibition Design Team.

The two artists began by giving a brief overview of their recent works, aided by a colorful slideshow.

Andres Hernandez, a local artist and educator, shared first, explaining the work he has done through the Revival Arts Collective (RAC), which he cofounded in 2011 to establish creative, alternative models to mainstream community economic development efforts. His work uses civic dialogue, microgrant-making, and “creative place-making” to encourage active citizen engagement in the process.

“Particularly on the South Side, where development is stalled, we think about what can we do as artists, designers, and creatives to spur conversation and spur initiatives,” Hernandez said.

In the past few years, the RAC instituted the Sol Street Festival, which reimagined a vacant lot at 62nd Street and Cottage Grove Avenue; Revival Bronzeville, which focused on the Bronzeville Corridor on 47th Street and King Drive; and Saturday Sweets, a microloan program that raises money for art projects in Bronzeville.

“For us, we were thinking about how we can’t always get funding from institutions or philanthropy—how do we do our own microfund within our own neighborhoods?” Hernandez explained.

Amanda Williams, a Chicago-based visual artist who trained as an architect at Cornell University, followed Hernandez. Her discussion revolved, in large part, around the works in her first solo exhibition, Color(ed) Theory, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA), and the projects that informed them.

“Color(ed) Theory” is an extension of Williams’s 2015 project of the same name, for which Williams painted eight houses slated for demolition in Englewood with vivid colors to draw attention to the racial undertones of urban design and decay. At the MCA, Williams presents sculptures from this project, including a large pile of gold bricks.

“[In Color(ed) Theory,] it was really important to use the fact that these things go away without our knowledge, without kind of any understanding of how these systems work, as part of the project itself,” she said. “It was sort of the idea of a morning and kids going to school as being as common as these houses going away.”

“What I learned from this process…is that most of the foundations of these houses are brick and that the Chicago common brick is valuable from a building standpoint because it has this certain resilience,” Williams added. “You can imagine that these lots that are being razed [from] these bricks…that’s actually a gold mine.”

Williams also spoke about two other aspects of her exhibition at the MCA: a series of eight maps titled “Chicago is Iraq?” and a narrow gold room, visible but inaccessible to museum-goers.

“‘Chicago is Iraq?’ is, of course, kind of playing off the idea of ‘Chiraq’ and the controversy around that: it presents this neutral illustration of literally what Iraq over Roseland, over Auburn Gresham, over Austin looks like so that you can really imagine the tension between those two places, as sites of trauma but also sites of possibility,” Williams said.

“And then, it’s really important for me to think about being invited inside a place that has historically not been very inclusive of people who look like me and what does it mean to provide this moment of access?” she added. “So I invited six residents of Englewood, all friends of mine but from different walks of life, to come in [to the MCA] and actually go into this room that was a scaled city lot—so a typical lot is twenty-five feet by 125 feet, this room is six feet by fifteen feet—and to really think of this idea of hidden in plain sight. And then to not allow access to anyone else to that room except those six people.”

Louise Bernard next took the floor, shifting the focus of the conversation away from the introduction of the design team to discussion of the museum itself. Although Bernard was formerly director of exhibitions at the New York Public Library and, before that, senior content developer and interpretive planner for the museum design firm responsible for the Smithsonian Museum of African American History, she talked very little about herself.

Instead, she turned to the model of the OPC designed by Todd Williams Billie Tsien Architects, first unveiled in May. The model shows a campus of three separate buildings: at the north of the site, the tallest building will contain the center’s museum, while buildings to the south will house a forum of multiuse spaces and a library, all arranged around a public garden and plaza.

“This project is one of revitalization—of really bringing a dominant, cultural voice but engaging with those communities around it. It’s very much a community project,” Bernard said. “I like to think of the museum as being, in many ways, the physical manifestation of the work of the Obama Foundation, which is itself about civic engagement; about what it means to be a citizen.”

Discussing the intentionality behind particular architectural decisions, Bernard spoke about the OPC’s presence on the landscape connecting Jackson Park and the lake, adding that it was designed to look metaphorically like a “beacon.”

“The building has kind of an iconic presence on the landscape. It’s something that people will be drawn towards,” she explained. “We have to be very thoughtful about how light impacts the building, because we will be preserving objects within, [is] that the building itself, while it seems like a fairly weighty edifice, will [through its materials] give a sense of lightness and translucency.”

The verticality of the building, Bernard said, is significant as it contrasts from other presidential museums, most of which are on one plane.

“We’re really thinking of this metaphor of movement, of a journey from the grassroots: the idea of individual agency moving up to a point of collective action,” she said.

“The Sky Room” at the very top of the building will be a space where visitors and local residents will be able to access what Bernard called a “remarkable view of the city and surrounding landscapes.”

Bernard also spoke in depth about what is being planned for the spaces within the OPC. She emphasized the idea of “democratic space” and the idea of the museum housing and sharing knowledge.

“It’s attached to a forum, which is where many of the programs will take place; these hands-on activities,” she said. “It’s the space where one will find the auditorium. A test kitchen. A recording studio. Other multi-purpose kinds of spaces where visitors and local residents will be able to come together and participate in these hands-on programs that speak to civic engagement…It’s a welcoming space. A space of convening. A space where we might find commissioned public art.”

Bernard also spoke to the narrative she intends for the museum exhibition to tell: a multidimensional story focused not only on Obama’s personal history, but also on how African American history and America’s history of racism informed Obama’s presidency.

“While the narrative of president Obama is certainly phenomenal in many ways, it’s deeply rooted in history,” she said. “So we really wanted to think of the history of which that watershed moment—the inauguration of the first African American president—came to be and that history is rooted in the history of the civil rights movement, in progressive movements.”

“And it’s rooted also in relation to those counternarratives that worked very precisely against the president and that we have seen come to the forefront unsettlingly today: those forces of racism, white supremacy all have to be accounted for to really make sense of the world in which we live.”

She closed with what the contents of the museum’s displays will be, touching on the importance of engaging around physical objects and how these will contribute to larger storytelling.

“I think of the idea of the museum itself as a place of stewardship: that we are housing and preserving artifacts that will be maintained for future generations and the importance of the object; of coming to this place and being able to commune, in a way, with individual objects that themselves tell a story,” Bernard said.

“It’s important for us all to be reminded of the power of those objects…This will be a space where artifacts do a lot of work,” she added. “You can see the range here. President Obama’s signing pen, for example…the importance of textiles in the First Lady’s dresses—which tell us not only about her own sense of style and dignity but about a sense of sartorial diplomacy and what Black style actually signifies to a broader world. And the Nobel Peace Prize, for example. So you can really see the richness, the wealth and how that connects to larger stories, larger storytelling.” Notably, the OPC will hold few physical copies of records from Obama’s presidency, which will instead be stored digitally.

Before the event closed with a series of questions from audience members, moderator Monica Chadha asked Hernandez and Williams to speak to the significance of inclusivity to the design team. Both spoke to the monumentality of their team being led by Black women, and how that fact is important and exciting to them.

“I’m sitting between two very fierce and intelligent Black women,” Hernandez said. “The fact that our team is very diverse and led by women is unheard of in design. I don’t take that lightly. I don’t think any of us should.”

Similarly, Williams said, “This is super exciting but also daunting because it hasn’t been done before in this way…the architects and artists are a community: we’re South Siders, we’re Black. All those things become assets when at some point in my life they’ve been told to me to be deficits…this is the kind of project I want to struggle through.”

Staff writer Michael Wasney contributed reporting to this article.

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly