In Chicago, at least, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) has started to seem like a part of the arts establishment. A Power Stronger Than Itself, George Lewis’s landmark history of the Black music collective, came out in 2008. And in 2015, a blowout fiftieth anniversary concert series and a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art further solidified the group’s legacy. With all this institutional ticker tape falling, it’s easy to forget what the AACM actually is: an insurgent arts collective, a case study in the use of communal organization to create visionary work. They’ve stuck to the same collectivist principles for over half a century, building a cohesive international community while writing a wealth of strikingly original music.

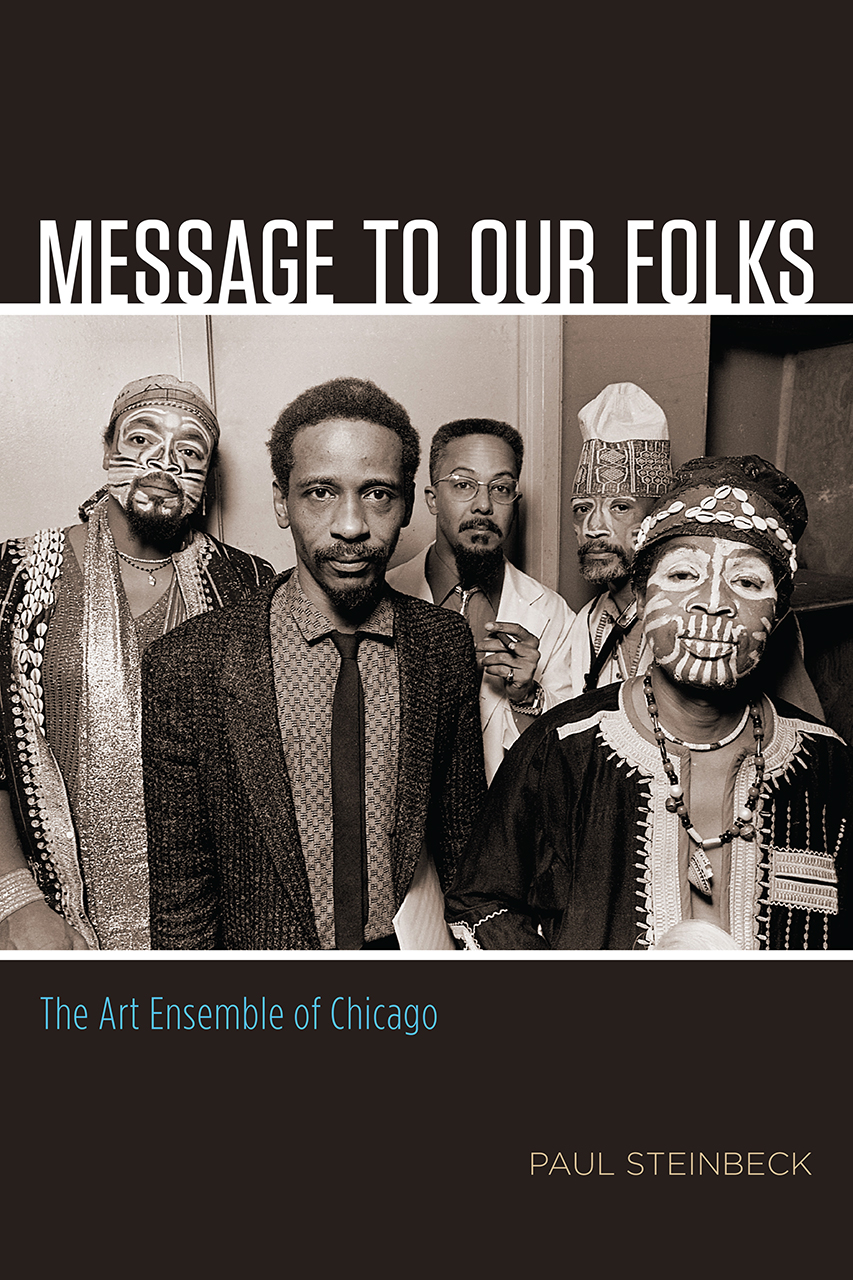

Message to Our Folks, Paul Steinbeck’s new history of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, the collective’s flagship band, vividly illustrates the AACM’s core value of interdependent creative practice. The Art Ensemble was a model of the AACM’s musical, cultural, and economic philosophy, and in the course of its career became one of the longest-lived and most celebrated experimental music groups in history. In this first comprehensive work on the Art Ensemble, Steinbeck evokes the adventurousness, range of expression, and sheer verve of these five virtuosos who, clad in African body paint, shamanistic garb, professorial jackets, and white lab coats, circled the globe playing—according to their motto—“Great Black Music, Ancient to the Future.”

Steinbeck, an assistant professor of music theory at Washington University in St. Louis, pieces together this first scholarly study of the Art Ensemble with an array of source material culled from over a decade of research. Using magazine and journal articles, ephemera like concert posters, and dozens of interviews, Steinbeck assembles a convincing argument that the Art Ensemble of Chicago was the most radical, and visible, exponent of the AACM’s values of social and musical interdependence.

He starts the Art Ensemble of Chicago’s story before the beginning, with the mass exodus of southern Black Americans to northern industrial cities in the Great Migration of the early 1900s. Steinbeck vividly describes the “black belt” of the 1950s, recounting the cosmopolitanism of the city within a city, with its Southern-style social life of bustling promenades, churches, and nightclubs. Three of the Art Ensemble’s members—Malachi Favors, Joseph Jarman, and Roscoe Mitchell—grew up in Chicago, each enraptured by church music and the South Side jazz scene. They honed their chops and jazz fanaticism in the Army, and then met in music theory classes at Wilson Junior College.

These three young musicians found their Chicago community in Richard Abrams’s Experimental Band. This group—influenced by the “weird records” of Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, and John Coltrane, as well as new currents in classical composition—evolved into the AACM in response to a few decisive economic and political shifts that hit the South Side in the 1960s. Amid slowing population growth and economic downturn, the city of Chicago passed an ordinance requiring clubs to pay a high fee to host large bands, a law that encouraged nightclubs to hire DJs. When the 1964 Civil Rights Act required the city’s two musicians’ unions to merge, the white North Side branch shuttered its South Side office and favored white musicians within the union.

Alarmed by these changes but seeing an opportunity to channel the creative energy contained within The Experimental Band and other groups, Richard Abrams and three other musicians—Phil Cochran, Jodie Christian, and Steve McCall—wrote the charter for a nonprofit called the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. The AACM limited its membership to Black musicians, and—vitally—required its members to play only original works, most often in concerts that resembled classical recitals more than jazz gigs. They termed their musical product “creative music,” rather than “jazz,” a term they regarded as having been used by the white music industry to package Black music. By the mid-sixties, Chicago had its own organization to train young musicians, employ working players, and bolster the African-American community’s pride for its artists.

The foundation of the AACM energized Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, and Malachi Favors. They soon formed groups, quickly gaining acclaim from critics, if not necessarily the public. Soon, trumpeter and St. Louis transplant Lester Bowie catalyzed the Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble when he walked into an open AACM jam session. The always-memorable Bowie maybe summed up the spirit of the early AACM best when talking about that experience. As Steinbeck quotes, “I said this is home here. As a musician there’s always a couple of dudes you can hang with. But here was thirty or forty m—f—s all in one spot. I mean Roscoe Mitchell, Anthony Braxton, and Abrams, eccentric-type cats.”

Throughout his narrative of the band, Steinbeck situates the group’s philosophy of musical and financial interdependence in context, describing the strategic decisions that in accumulation helped the Art Ensemble rise to the top while maintaining its eccentric practice. The group began its international career in 1969 when Lester Bowie and his wife, successful R&B musician Fontella Bass, sold off their possessions to fund a group trip to Paris. There, the Art Ensemble found its first wide audience in the Black expatriate American jazz clubs. French music press adored the group, thanks in part to the political climate in Paris, which was still electrified by the mass Leftist uprising of May 1968. Many journalists assigned a positive moral value to experimental jazz, viewing Black Americans as symbols of the Civil Rights movement. Despite (or perhaps thanks to) this confused coverage, the Art Ensemble was soon signed to French record imprint BYG Records.

Now renamed the Art Ensemble of Chicago and joined by drummer Don Moye, the band began touring the continent, bringing in money on a financial model of collective ownership that allowed them to reinvest in the band. After returning to the U.S., they allowed each other ample time to work with their side projects while periodically coming together to work on Art Ensemble music.

Over the course of the 1970s, the Art Ensemble became the AACM’s most popular group, touring several continents, releasing a torrent of albums for several decades, and becoming one of the most popular international acts in jazz—experimental or not—until they retired for good in 2010.

Steinbeck enriches his historical reading of the band’s career with three detailed musical analyses of two albums and a concert film. Members of the group played a vast array of instruments: Mitchell and Jarman principally saxophone, Bowie trumpet, Favors upright bass, and Moye a vast drum set augmented with hundreds of small percussion instruments. But they also employed scores of “little instruments”—noisemakers, horns, chimes, and more—that furnished a limitless palette of sonic possibilities. In his musical analysis, Steinbeck provides a precise and illuminating picture of the interplay between the players, as well as the group’s complex and intuitive improvisational strategy, which employed what Steinbeck calls “intermusical” techniques, such as quoting melodies from different periods in the history of jazz. Steinbeck also investigates the group’s “intermedia” techniques—elements like spoken word, elaborate costumes, and the theatrical antics—that place the group’s music in some transcendent place between music, poetry, and performance art. These chapters of analysis break down the complex architecture of the Art Ensemble’s style to reveal the musical and emotional concerns that propelled the group throughout its career: joy, sorrow, virtuosity, restraint, gonzo humor, cosmic wonder.

Since the Art Ensemble officially stopped performing in 2010, collective memory of the group’s exploits has faded—after all, Bowie died in 1999, Favors in 2004, and Mitchell, Jarman, and Moye are all in their seventies. Steinbeck performs a vital role in drafting a comprehensive study of the group, but his book’s success in telling the Art Ensemble’s story raises a whole new set of questions about the details of the group’s career. Steinbeck covers the band members’ early years with a measure of psychological insight that evaporates as the story progresses to the group’s more lucrative decades. The book left me wondering how success changed the Art Ensemble’s group dynamic and relationship to the AACM. And Steinbeck provides just enough information about the band members’ side projects to tantalize the reader. Can we hear more about Joseph Jarman’s intense Buddhist practice and Malachi Favors’ role as elder statesman of the Chicago creative music scene? Let’s hope that Message to Our Folks is the first in a long line of books that shed light on the AACM’s great players and groups.

An anecdote that neatly illustrates the AACM’s whole philosophy comes near the book’s end. In the 1980s, Lester Bowie lived in New York City, where he had a falling out with a young Wynton Marsalis, the talented young trumpeter who worshipped the traditional jazz of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. Marsalis thought Bowie didn’t respect jazz heritage, Bowie regarded Marsalis as a sellout, and soon the two were regularly exchanging hostile words in the pages of magazines. Marsalis even used his role as senior creative consultant to Ken Burns’s Jazz to diss Bowie. In that documentary’s sparse coverage of the AACM, the narrator says, that the Art Ensemble “attracted its largest following among white college students—in France,” a claim that Steinbeck dismisses as inaccurate, considering the group’s development of a global audience in the 1970s and 1980s. The feud came to a dramatic head when Marsalis showed up at a Bowie gig, trumpet in hand, to challenge Bowie to an old-school improvisation battle. Bowie didn’t take the bait, imperiously calling Marsalis “boy” and chiding him for interrupting. “Rebellion is the actual tradition of jazz,” Bowie said in an interview.

The Bowie-Marsalis feud has all the ideological clarity of a political cartoon, and demonstrates the anti-establishment mentality that characterizes the AACM. When the ever-spiritual Malachi Favors added the phrase “Ancient to the Future” to the group’s slogan “Great Black Music,” his choice of words implied not only that the band’s group improvisations spanned the history of music, but also that the sounds they recorded today would be ancient—and vital—in some distant future.

Paul Steinbeck, Message to Our Folks: The Art Ensemble of Chicago. The University of Chicago Press, 2017. 336 pp.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.