At around 7:30am each weekday morning, John Siangho helps his son—a second-grade CPS student at the Regional Gifted Center through Carnegie Elementary in Woodlawn—get ready for another day of remote learning. The two of them wash up, chat during breakfast, and at 8:30am, fifteen minutes before class officially begins, Siangho’s son goes to his desk, turns on his school-issued device, and waits for his teacher to let him into the virtual classroom. He spends most of the day watching live instruction, with a few breaks to snack, read, or move around. By 3:20pm, his digital class has wrapped up and Siangho’s son spends another thirty minutes filling out worksheets or submitting homework.

“I’m making it sound, with all the time hacks, like it’s super regimented and routine,” Siangho said. “The morning is a little bit more like that, but the afternoon, not as much.” This is what school has become for Siangho and his son during the COVID-19 pandemic: several hours in front of a screen, learning from teachers and peers from afar.

In August, after months of deliberation on whether and how children should re-enter schools in the midst of a pandemic that had already killed thousands within the city, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) decided to have students continue with all-remote learning rather than moving to a proposed hybrid model—which would see students at school two days a week for in-person instruction.

There was strong opposition to the hybrid plan, both from parents, the majority of which did not intend to send their children to physical classrooms, and from the Chicago Teacher Union (CTU), which organized protests, but this left a herculean task for the district—and for hundreds of thousands of children, parents, and teachers who have been working against years of inadequate funding allocation—to meet the needs of young Chicagoans who rely on the schools for more than just education. CPS had to address multiple issues, including device shortages, internet inequities, and teacher support, to ensure that the 355,000 students enrolled in public schools throughout the city received equitable education services.

Now, with COVID-19 cases on the rise again and CPS announcing that teachers and some students will return to school next week, and the rest in February, worries abound that reopening schools will not improve the educational experience of children in communities where COVID-19 positivity rates are the highest—and may put them at risk.

When classes began last September 8, the first two weeks of school saw an additional 3,821 cases of COVID-19 and thirty-five deaths in Chicago, with a positivity rate around 5.2 percent, close to the city’s goal. However, many neighborhoods on the South and West sides had positivity above ten percent. The need to keep students from catching and spreading COVID-19 in school buildings seemed clear. However, educators and parents continue to fear that remote learning structures are less than optimal for many students and will further penalize children from poorer neighborhoods. And while CPS has implemented policies and processes to try and meet their students’ needs, their opacity has made it difficult for anyone outside the district to assess their impact during this unique public health crisis.

Different stakeholders have made convincing arguments for sending children back to school as well as for keeping them at home. While COVID-19 has only killed four children or adolescents aged eighteen and under in Cook County, representing about 0.1 percent of total deaths, children can still suffer from COVID-19 and spread the infection to others in their communities (although it is still unclear how infectious children are in comparison to adults).

On July 23, 2020, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released suggestions called the “Importance of Reopening Schools,” which cited the relatively few child cases and deaths from COVID-19, the value of developing social and emotional skills, the creation of safe environments from schools, and the facilitation of physical activity as reasons to “[reopen] schools as safely and as quickly as possible given the many known and established benefits of in-person learning.” However, in a statement, Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) President Jesse Sharkey voiced his uneasiness that this call for in-person learning may have resulted from “Trump successfully bullying the CDC to revise its ‘guidelines’ and risk the lives of students, their families and their educators by forcing in-person learning.”

Dr. David Zhang, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Chicago, also mentioned the importance of in-person learning, but told the Weekly that safety shouldn’t be overlooked. “We know that for younger children, school doesn’t just provide educational instruction. It’s extremely important for their social and emotional skill development, things that are just unable to be replicated in an in-home environment,” Zhang said. “Young kids need to be in groups, learn how to interact with those outside their family, and develop and maintain friendships.”

However, he also explained that while most children will have less severe COVID-19 infections compared to adults, he has seen children with pre-existing conditions requiring hospitalization. Additionally, some children can develop multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), a condition thought to be spurred by COVID-19 infection that causes organ systems to inflame and can affect the function of the heart, lungs, kidneys, and brain. And while rare, there have been a few cases of MIS-C in Chicago, with patients requiring hospitalization and frequent monitoring in intensive care units.

Every teacher that the Weekly reached out to also had concerns about returning to in-person learning before school staff received the personal protective equipment (PPE) and sanitation supplies necessary to function safely prior to a vaccine being deployed. “Ideally, there would be an effective treatment and a vaccine for school reopening,” said Rachael Nicholas, a ninth-grade world studies teacher at Taft High School in Norwood Park. Bethanie Smith, a preschool teacher at William H. Ray Elementary in Hyde Park agreed. “I am worried about some children falling behind, but the need for a safe and healthy learning environment outweighs that concern,” she said. “The emotional trauma that all stakeholders would suffer if young students and their families became ill or worse is an insurmountable issue that I can’t even imagine.”

Mary Winfield, a teacher at Pilsen’s Benito Juarez Community Academy, expanded on the idea that the role of school in some communities goes beyond just teaching and supporting students. “My ideal reopening plan would be to remain remote until there is a vaccine and to treat the students and their families with care,” she said. “We can take this time to help families connect in ways that support the school communities. We can focus on systems of support and let go of systems that aren’t useful or are harmful.” Winfield added that schools are often in a unique position within communities to be able to provide direct services to a large number of families. “My school—as have many others—functioned as a food and diaper distribution hub. We also established a fund for families in need. This is the real work of schools rights now.”

Adapting an entire learning system to at-home learning introduces new variables for students and schools, and many fear that the shift would be detrimental to areas that have already been affected by decades of inequity in funding, staffing, and district support—mostly schools on the South and West sides. “The biggest pitfall last spring was the gross inequity that we’ve been fighting against for years,” said Michael Shea, a twelfth-grade civics teacher at Kenwood Academy in the Hyde Park-Kenwood neighborhood. “We all know those inequities affect grades, attendance and the material support that kids need to learn and grow. Some of the same challenges are still present this fall—access to devices, access to reliable connectivity, access to health and wellness coverage and support.”

In March, just weeks after in-person schooling was cancelled for all students, Dr. Janice K. Jackson, Chief Executive Officer of CPS and LaTanya McDade, Chief Education Officer, released a Five-Year Vision for Chicago Public Schools. Interspersed with planning and goals to the three main commitments of academic progress, financial stability, and integrity, were additional plans to address the district’s ability to increase equity with an emphasis on supporting underserved populations. On August 20, the CPS Equity Framework was released and CPS CEO Jackson said, “I continue to believe that CPS is a district on the rise and our remarkable academic progress is stronger than a pandemic…With equity at the heart of our district’s vision for the future, we will press on toward our mission of providing our future leaders with the world-class education that they deserve.” To that end, CPS reports having spent $119 million in resources to directly support schools during the pandemic. This has included funding for computing devices, cleaning supplies, masks, and additional services.

However, budgeting has long been an issue for CPS. The CPS district, which oversees 642 schools and employs 21,000 teachers and 16,000 other staff, had an operating budget of $6.32 billion in fiscal year 2020. Funding to individual schools is parsed out using a method that many say perpetuates the divestment from neighborhoods most affected by population flight (predominantly Black and brown communities), and deepens inequity: student-based budgeting. Mayor Lori Lightfoot campaigned on finding a better way to fund schools, and CTU has long been opposed to this method of allocating resources, referring to it as a perpetuation of racism. But during the announcement of the 2020-2021 school year budget in April, CEO Jackson said that “student-based budgeting” is the most equitable method available” and argued that the real problem is insufficient funding from the state and federal level.

Illinois estimates that CPS is only receiving sixty-four percent of the funding it needs to run effectively in the 2020-2021 school year, even as funding increased from the prior year by $191.3 million, with $125 million geared towards special education, college and career readiness, and supports for district’s schools in highest need areas. Jackson said that schools only receive about fifty percent of their funding from student-based budgeting, and alluded to using “equity grants” to ensure schools that need the most will get more funding.

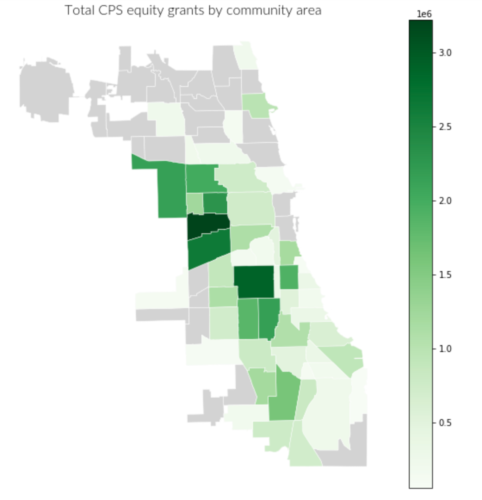

The 2020-2021 budget incorporated $44 million of equity grants given to 255 schools, using UIC’s Economic Hardship Index which looks at multiple factors including poverty, unemployment, housing, and income of students, to determine which schools would receive additional grant funding. Because student-based budgeting distributes dollars depending on enrollment, equity grants often go to schools with low or declining enrollment so that students who attend those schools can continue to receive the same quality of services, even as student-based funding declines. Per CPS, “Schools have the autonomy to spend equity grant funds based on their individual needs, whether that’s an additional support position, after-school programming or academic supports.”

Most equity grants went to schools on the South and West sides. On average, schools received $174,000. The largest grant, at $679,600, went to Bronzeville Scholastic Academy High School, and the smallest grant, at $4,800, went to Leif Ericson Elementary Scholastic Academy in East Garfield Park. Schools in North Lawndale, New City, La Villita, East Garfield Park, and Englewood received the most in equity grants.

But the challenges of remote learning cannot be addressed by increased funding alone. Prolonged disinvestment from communities means that even with increased funds, the infrastructure required for learning from home simply doesn’t exist. Last spring, Kids First Chicago estimated that 110,000 CPS students lacked access to broadband internet, and similar numbers of children lacked access to personal computing devices. Chicago Connected, an initiative spearheaded by local hedge fund CEO Ken Griffin, seeks to bring together the city and other philanthropists to deliver broadband to households in need by way of internet service providers (ISPs) in Chicago. The plan was to get every child the resources they needed to succeed in remote classrooms this fall.

Many believe that Chicago Connected is a step in the right direction for CPS, which plans on continuing the initiative for four years without cost to certain eligible families. Eligibility was decided based on free or reduced lunches, Medicaid qualifications, the UIC Economic Hardship Index, and other factors that can make it more difficult to learn, such as English not being a first language or an unstable living situation. Karinna Astorga and Joel Rodriguez are both community organizers from the Southwest Organizing Project, one of the community-based organizations (CBOs) that was tapped to help connect families with internet services in Gage Park and West Eldon. Astorga works specifically with supervising SWOP’s Chicago Connected Initiative. They both say that Chicago Connected is a unique initiative that is going as well as could be expected, although there have been some difficulties. “I think an apprehension is undocumented families giving out information and I think that that is always a concern,” Rodriguez said.

Another concern parents had was that the service would actually end up costing them money. Still, they noted that Chicago Connected’s move to team up with CBOs was incredibly beneficial. “A lot of families have been used to hearing one thing which turns out to be something else. I think the best move was to put it in some of the CBOs that have established rapport with communities,” Rodriguez said. “That helps apprehension go down considerably.”

The transient nature of renting has caused some issues for families seeking out service, as internet service providers can only set up one unit per address. “We’ve got families that rent out the basement or the attic. If there’s already existing Comcast or any internet, that’s a challenge that they’ve been trying to figure out with hotspots,” Rodriguez said. “That’s just the nature of our communities and dynamics we have to confront. There’s very little a company can do if there’s already an existing line. They can’t add another to an apartment that truly doesn’t exist.”

Astorga said that most people have been appreciative of Chicago Connected’s services, and that they are looking forward to hosting digital literacy events to help parents and students learn how to use Google Classroom. However, a month into the 2020-2021 school year, many families still did not have access to the tools that make meaningful virtual learning possible. Only 29,000 families had been signed up as of October 8, despite dozens of CBOs helping connect families with internet service providers. As Winfield said, “CPS has been underfunded for so many years that schools had no way of providing a device for each student in a short amount of time. Next came the hurdle of reliable internet. Many didn’t—and still don’t have it.”

Even if reliable broadband was provided to everyone, CPS families have faced complications adjusting to remote learning. In the spring, parents and students alike struggled to keep up with multiple platforms to access and submit classwork and assignments. Siangho said: “I think there were nine or ten different apps that I had to learn. It was really difficult, with different submission policies for each of these apps: do you need to print it out? Scan it and send it? Is the homework submitted on the app? Do you need to use your Gmail email? Dropbox?”

Shea, a teacher who has kids of his own, noted that CPS teachers who are also parents often face the same difficulties as students and their families. “If I’m not receiving support from the district as a CPS teacher or as a parent, then I know my students and their families will struggle as well,” he said. “It doesn’t matter if someone is working or not, parents and caregivers can help kids when they know how and when they have the time and resources to do so, and they struggle when they don’t.”

This fall, CPS centralized their tools using the Google Education Suite. Siangho said that the platform experience is now more streamlined but “the frustration of technology” continues. “It’s less about experiencing a technological glitch,” Siangho added, “and more that a significant amount of your mental capacity is devoted to worrying about it and knowing that somehow you’re gonna have to deal with it.”

Moreover, CPS continues to struggle with the fact that remote learning remains inaccessible to the thousands of students who do not have dedicated personal computing devices at home. This fall, Siangho’s son received a school-issued Chromebook, but last year, technology distribution was more limited. “CPS asked those who had devices to leave resources for others,” Siangho explained. CPS was already gearing up to buy more computing devices to provide every child in every school in the district with a computing device as part of their five-year plan to close the digital divide, which remote learning has intensified. According to the district’s CFO emergency spending report details, as of August 31, CPS had purchased an additional 90,000 personal computing devices, including Chromebooks, iPads, and Dell laptops; 12,000 hotspot units; and 100,000 pairs of headphones beyond what they had planned. In mid-August, CPS announced that they had distributed 128,000 computing devices and that they intended to distribute another 36,000 this school year.

No matter how CPS progresses with increasing the equitable funding within its schools, the lack of publicly accessible data on its initiatives is concerning, especially given their commitment during budget meetings in August for resource equity and fair policies. In September, the Weekly submitted public records requests under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to the CPS FOIA Center, asking for all records with aggregate data on the number of families or students enrolled in the Chicago Connected Initiative. But this FOIA request was denied by CPS, stating that it would “require CPS to create a record it does not normally maintain within the course of business.” In May, when the initiative was initially discussed and a presentation was released to the city, a database to collect this data was listed as a goal to measure project performance. But the data has yet to be made available. In order to make good on the promise of equity, it will be important to release data about the district’s progress.

The Chicago Connected Initiative’s rollout paves the way for a similar idea promoted on the citywide ballot as a non-binding referendum, “Should the City of Chicago act to ensure that all the City’s community areas have access to broadband internet?” 90 percent of voters said yes. However, by not knowing which children still struggle with access to remote schoolwork, other support systems are left to figure out how they may be most beneficial. And there are a myriad of issues that make remote learning a struggle.

On January 3, a group of 32 aldermen sent a letter to both Mayor Lightfoot and CEO Dr. Jackson, voicing concerns about CPS schools reopening this month. They offered 9 steps to improve trust among families, educators, and the school system. Some of these steps include matters CPS has repeatedly failed to address, such as “reducing screen time, especially for students in early grades” and “promoting clear public health criteria for reopening,” calling attention to CPS stepping away from using a case positivity benchmark of 5 percent to an “infection doubling in fewer than 18 days” as positivity rates have ranged between 8.3 and 13.1 percent over the last month.

In addition to calling for increased transparency from CPS, the aldermanic letter also called for increased collaboration with CPS, teachers, and the CTU. “We have been alarmed to see, read, and hear consistent testimony from educators expressing their profound frustration with the status quo and how it hinders their ability to do their job.” In its final sentences, the letter’s signatories commit to assisting CPS to achieve “true buy-in from and collaboration with parents, communities, and organized labor… A successful reopening plan must inspire public trust through transparency, communication and collaboration.”

Late that evening, Jackson released a nine-page rebuttal, declaring that opening up schools can be done safely and that schools have not been shown to be a large contributor to COVID-19 transmission. This builds on what Dr. Allison Arwady, commissioner of the Chicago Department of Public Health, discussed during the announcement to bring children back into schools on October 16. At that time, Arwady pointed out that COVID-19 spread in schools was lower than initially feared and that students suffer from remote-only learning. “The unfortunate fact is that despite our best efforts and the heroic work of teachers to make remote instruction effective for CPS students, it is a poor substitute for in-person learning for many of our most vulnerable students,” Jackson said.

The current plan will see certain groups, including pre-kindergarten and cluster students, who require moderate to intensive supports, returning to school on January 11; K-8 students are scheduled to return to schools February 1. Although CPS claims to have established several COVID-19 mitigation strategies for in-person learning, on Monday multiple teachers across the city reported insufficient PPE, inability to distance, and inadequate ventilation improvements.

On Tuesday, January 5, thousands of teachers and support staff did not show up for their first day of work ahead of the spring semester.

Rachael Nicholas spoke to the state of reopening and how it would affect Taft High School, where she teaches. “We have a cluster special education program at our school and I believe they will be returning. I do not know the number of students but it is pretty small,” she said. “I still don’t think it is safe because the community spread is too high. In addition, the students in the cluster programs often need help eating and using the bathroom, so the teachers will be in close contact with the students.”

Even in December, the percent positivity for those under the age of eighteen was an alarming 16.5, an increase from the first weeks of remote learning in September when positivity for the same group was just 7.4 percent. If and when schools fully reopen, CPS has said that it will try to make sure that COVID-19 mitigation strategies will be provided for incoming students. CPS has hired contact tracers to work specifically with schools and will require face coverings, daily screenings, COVID-19 testing, and will hire additional custodians and try to ensure every classroom has proper ventilation.

On the other hand, CTU officials maintain that CPS should keep students and staff out of schools, saying that clerks—who were told to return to school buildings despite an arbitration ruling for clerks to work from home—should not have to choose between doing their job and protecting their health. “School workers are becoming infected with COVID-19. Some are dying, and CPS has taken no new steps to ensure this won’t continue to be the case,” CTU officials said in a statement.

Zhang noted that many CPS families are facing a double-edged sword where the safety of in-person learning is deeply concerning, and the logistics of remote learning are largely unsustainable. “For some households in difficult situations, the question isn’t: should I send my kid to school? The question is: I don’t have a choice, how do I send my kid to school safely?” Zhang said. “I would urge parents to evaluate their family situations and determine what’s best for their families.”

During the Chicago Board of Education meeting on November 18, LaTanya McDade reported that plans to reopen were being made to reduce the racial inequities in grades and attendance that have worsened during remote learning. The divide is greatest for students with insecure or no housing. And while there are plans to increase child learning hubs—places around the city where students can access the internet and be supervised by an adult—there are currently only fifteen hubs with limited enrollment, meaning many children who may benefit from this are being excluded simply because of space.

For their part, CTU’s position is to improve remote learning instead of trying to force school reopenings. They have stated a desire to increase remote learning’s effectiveness by ensuring that internet and laptop access is available to all students, increasing the number of teaching assistants available during remote learning, and providing learning opportunities to caregivers on how to assist their students. In October, CTU conducted a survey with Lake Research Partners (LRP) of 600 Chicagoans—seventy-two percent felt that “Chicago schools should not be re-opened until the spread of the virus is controlled.”

Rodriguez emphasized that no matter what CPS’s decision is on school reopenings, SWOP and organizations like theirs are committed to serving the students and families who have been hardest hit by the pandemic: “These are really extraordinary times, and extraordinary times require folks to use imagination and use all the resources they have at their disposal to try and tackle this monster,” he said. “So that’s what we’re doing.”

Despite the struggle of adapting to remote learning, there have been some positive additions. Brittannee Rolle, a twelfth-grade AP English teacher at Butler College Prep in Pullman (and a contributor to the Weekly’s Best of the South Side issue), mentioned some new programs at her school that have emerged during remote learning. “We were able to start a club that had guest speakers on topics of interest to young Black girls in my school. Students loved talking about topics they were interested in and engaging with women from different fields,” she said. “I think it taught me to utilize virtual features more often even when we go back to meeting in person at school.”

When asked what his hopes were for the rest of his son’s academic year, Siangho responded, “Survival.” He laughed and explained, “This is not a banner year for education anywhere, right? But as long as he is kept engaged, that’s my thing—I want him to continue to be engaged so that the love of learning does not stop.”

This story was supported by a National Association for Science Writers (NASW) Diversity Reporting Grant.

Elora Apantaku is a medical doctor and writer. She last wrote about a study linking neighborhood characteristics and resources to COVID-19 mortality rates.

Charmaine Runes is a graduate student at the University of Chicago’s Computational Analysis and Public Policy program. She last wrote about biking for environmental justice on Chicago’s West Side.