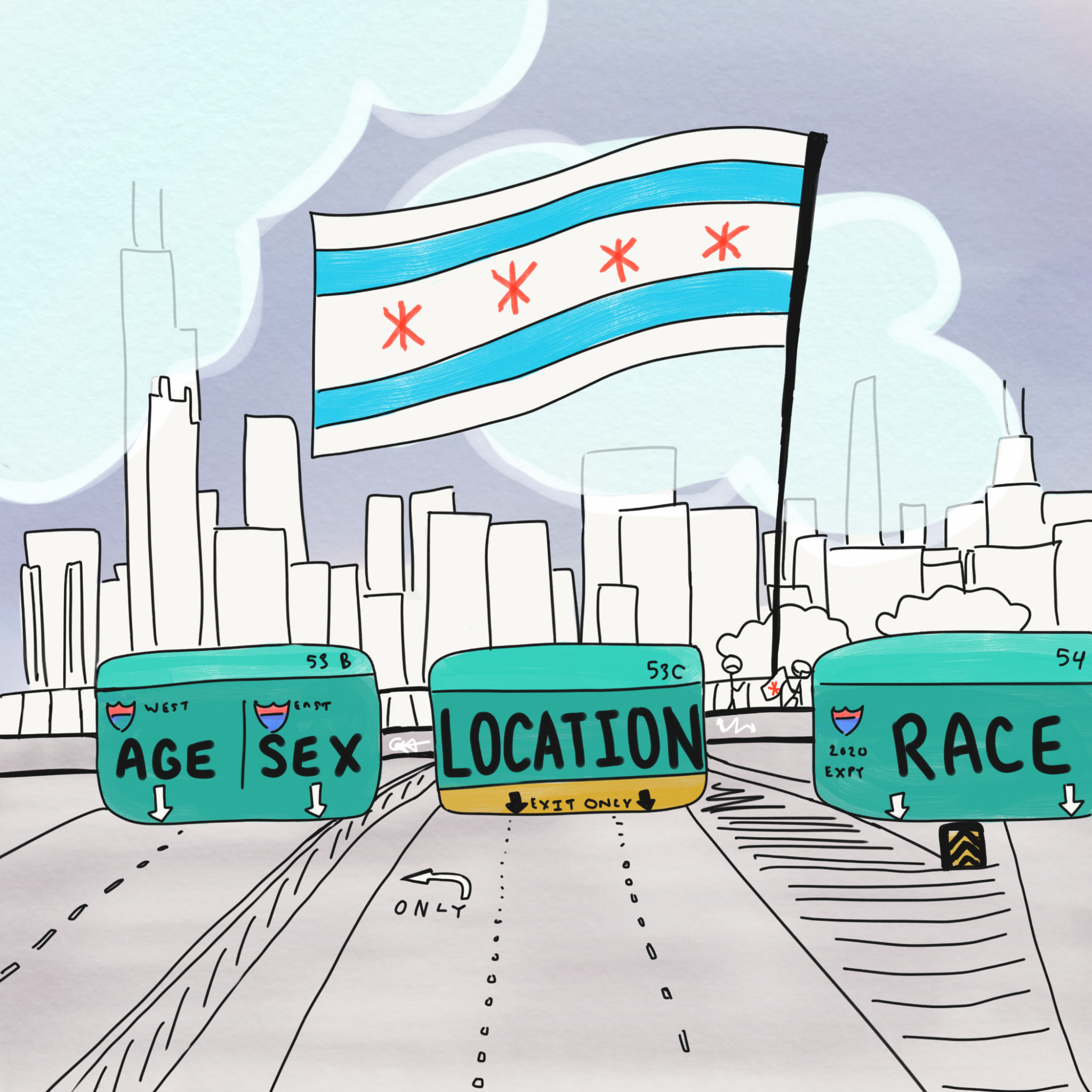

In April, Weekly data journalist Bea Malsky designed an online tracker that illustrates where COVID-19 deaths in Chicago are concentrated and which populations are hardest hit by the pandemic. The tracker pulls Cook County Medical Examiner (CCME) data from the Cook County Data Portal and shows the number of COVID-19 deaths by community area and by the race of each person who has died. By mapping out which areas were hit hardest—in a city still facing the effects of decades-long discrimination and segregation—the connection between communities of color and COVID-19 cases and deaths is readily apparent. “Illness and mortality appear along geographic and racial lines of disparity, neighborhood by neighborhood,” Malsky wrote at the time.

In May, Molly Scannell Bryan, an epidemiologist at UIC’s Institute for Minority Health Research, contacted Malsky about the tracker. Scannell Bryan wanted to know how Malsky had processed the CCME’s data to report COVID deaths by race and location, because she knew that CCME occasionally makes corrections after data is posted. Malsky had made sure the tracker took that into account. “I reached out to [Bea] in particular because in the death data, race and ethnicity coding changes over time,” Scannell Bryan said. “For recent decedents, the race and ethnicity [information] is not always accurate. Some of the records are corrected later, but even with the corrected data misclassification is still possible.” This can cause underrepresentation of Latinx deaths in the final data, because often those deaths are initially reported as “white.” Malsky’s tracker reports the most recent demographics available, so if CCME makes any changes to it, they are reflected in the tracker the next day.

Scannell Bryan researches health disparities: why and how certain communities are affected more than others by myriad health issues. She became interested in exploring COVID-19 as soon as the city shut down. “When COVID-19 started erupting in spring,” she said, “I wanted to understand how it was affecting Chicago specifically.” Her approach found a focus after reading a study that piqued her interest. Researchers from Harvard University had compared air pollution levels to death rates in thousands of counties across the United States. “Counties that had high pollution tended to be urban counties, and that was particularly in the spring and summer where deaths were concentrated, too,” Scannell Bryan explained. Since Chicago is encompassed by one county—Cook—she decided to look at census tracts. Chicago has approximately 1,000 census tracts, each containing roughly 4,000 people.

In November, Scannell Bryan co-authored a study in Annals of Epidemiology that drew upon CCME data and other information to examine the relationship between COVID-19 mortality and Chicago’s neighborhoods. The researchers focused on 795 census tracts in Chicago that had experienced a combined 2,514 COVID-19 deaths through July 22. For each tract, they looked at thirty-three different variables that they suspected could affect either COVID-19 infection risk (such as living in dense housing, transportation habits, and access to broadband internet at home) or mortality risk (health care access, rates of comorbid conditions, poverty rate, and air quality).

Their findings seemed to mirror the results of similar studies conducted across the country: more COVID-19 cases, and more COVID-19 related deaths, are occurring in Black and Latinx communities than in white ones. Black deaths from COVID-19 are disproportionately higher than white or Latinx deaths, and Latinx deaths from COVID-19 occur at a younger age compared to white counterparts, at sixty-three years, compared to seventy-one for white residents. The study also revealed that mortality rates were not evenly distributed throughout the city as much as they were concentrated in certain neighborhoods with shared characteristics. Scannell Bryan said this was “not so surprising for an infectious disease,” but they did not see a strong effect of dense housing, where multiple apartment buildings with more than twenty units are located. Instead, “what we saw rise to the top were these indicators of barriers to social distancing, specifically internet access.”

Diane Lauderdale, the chair of the University of Chicago’s public health department, cautions that while census tracts give researchers an opportunity to look closely at specific areas, they may also lead to inaccurate assumptions about certain locations because of additional variables that aren’t present in the census data. “Because they do not have very many individual characteristics for the COVID cases beyond age and race, contextual variables that are identified by this analysis are not actually risk factors at the contextual level but are analogs to individual characteristics that put individuals at risk,” she explained.

This means that the neighborhood characteristics the study identified are not definitive risk factors for individuals becoming infected or dying from the disease, but instead may serve as proxy indicators for larger problems that make surviving a pandemic more difficult. Internet access, for example, “might be a proxy for something else, but it might also flag neighborhoods that had an easier time navigating the shutdown without leaving home,” Scannell Bryan said. She added that if true, this suggests health outcomes could be improved with policy that increases both healthcare access and people’s ability to stay in their homes.

Lauderdale said that Chicagoans should follow the Chicago Department of Public Health’s advice on how to protect themselves from COVID-19. “I have been very impressed with how the city has reached out to a number of experts across the city for advice and brought together the research community to lend their expertise,” she said. But she also acknowledged that decades of inequality have made it difficult for many residents to remain healthy. “Many of these circumstances are within Chicago’s control and some are broader national problems that we are seeing in Chicago.”

Scannell Bryan emphasized the importance of encouraging public health policies and messaging that is consistent and scientifically driven. “Yes, individual decisions matter,” she said, alluding to washing hands, wearing masks, and social distancing, ”but the burden of solving this cannot be put solely on the people who are already disproportionately burdened by COVID-19. Providing additional resources to support those living in these neighborhoods is a more equitable approach.”

Elora Apantaku is a medical doctor and writer. She last wrote an Illustrated FAQ to COVID-19.