Diane Limas, eighty, has lived in her two-flat building in Albany Park for more than three decades. She loves the neighborhood, particularly its proximity to the Chicago River, where she sometimes goes fishing. But after her property taxes soared a few years ago, Limas is increasingly worried about her future.

Limas is the board vice president at Communities United, a racial justice organization that works to advance affordable housing, immigrant rights, and restorative justice alternatives in Chicago. She has gone on the record before about the impact of property tax increases. Between 2019 and 2020, her property taxes nearly doubled, rising from $5,908 to $10,693. The increase followed the redevelopment of a neighboring property into a luxury home, which Limas believes significantly inflated property values in the area.

While Limas, who lives on a pension and rent from her sister and brother-in-law living upstairs, managed to absorb the tax hike, she is concerned about what future increases might bring.“Every time I get an increase like this, I have to reevaluate my finances,” she said. “I don’t want to be pushed out. Where am I going to live? With my kids? In a nursing home? That’s not how I want to spend my old age.”

Limas does not qualify for the senior tax freeze program, which caps eligibility at an annual household income of $65,000.

Across Cook County, soaring property taxes fueled by rising levies and shifting tax burdens are squeezing low- and middle-income homeowners. According to Cook County Assessor Fritz Kaegi, “more than 300,000 homeowners across Cook County have seen their tax bills spike by at least 25%” over the past four years, deepening the financial strain on households already struggling with Chicago’s worsening housing affordability crisis. A bill introduced in Springfield this year that has Kaegi’s support could offer them some relief.

According to data from the Cook County Treasurer’s Office, while the total amount of property taxes in the county rose by 4% in 2023, homeowners bore a disproportionate share of the increase, with their tax bills climbing by an average of 15.9%. Property taxes on businesses fell by 7.8%.

The pain has been particularly acute in the south suburbs, where the Treasurer reported in 2023 that fifteen municipalities—thirteen of them predominantly Black—saw total homeowner tax increases exceed 30%. In Dixmoor and Phoenix, the total homeowner tax increases surpassed 75%.

Within the city, the total property tax increase was 2.8%, with businesses shouldering more than half of the additional costs. Yet in certain neighborhoods, particularly on the South Side, residents saw steeper hikes than other parts of the city. In Woodlawn and Washington Park, for example, property taxes rose between 5–10%.

The Cook County Assessor’s Office, which reassesses Chicago property values every three years, released its 2024 assessment data on January 1. The Cook County Board of Review, which has the authority to adjust property assessments through its appeals process, is now reviewing it.

Although the City Council unanimously rejected Mayor Brandon Johnson’s proposed $300 million property tax hike and passed a 2025 budget without an increase, homeowners fear that rising assessed property values will still translate into higher tax bills.

Javier Ruiz, an organizer with Pilsen Alliance, a housing justice advocacy group, said he receives two to three calls a week from residents and small landlords worried about property tax hikes.

“A lot of them are concerned about raising rents on their tenants,” Ruiz said. “They’re trying their best not to do it, to be good neighbors. But at a certain point, they have no choice.”

“Property taxes are rising faster than people’s ability to pay,” said Cook County Commissioner Bridget Gainer (10th District) during a 2024 public hearing on the issue. The financial strain can lead to foreclosures and displacement, she warned, while landlords facing higher taxes may pass on the costs to tenants, further tightening the city’s rental market.

Property taxes are a crucial source of revenue for Cook County. The property tax system is “budget-driven,” meaning that the total tax levy is set first, then divided among taxpayers based on assessed values. Property taxes fund schools, law enforcement, and other local services. Yet the system is far from perfect.

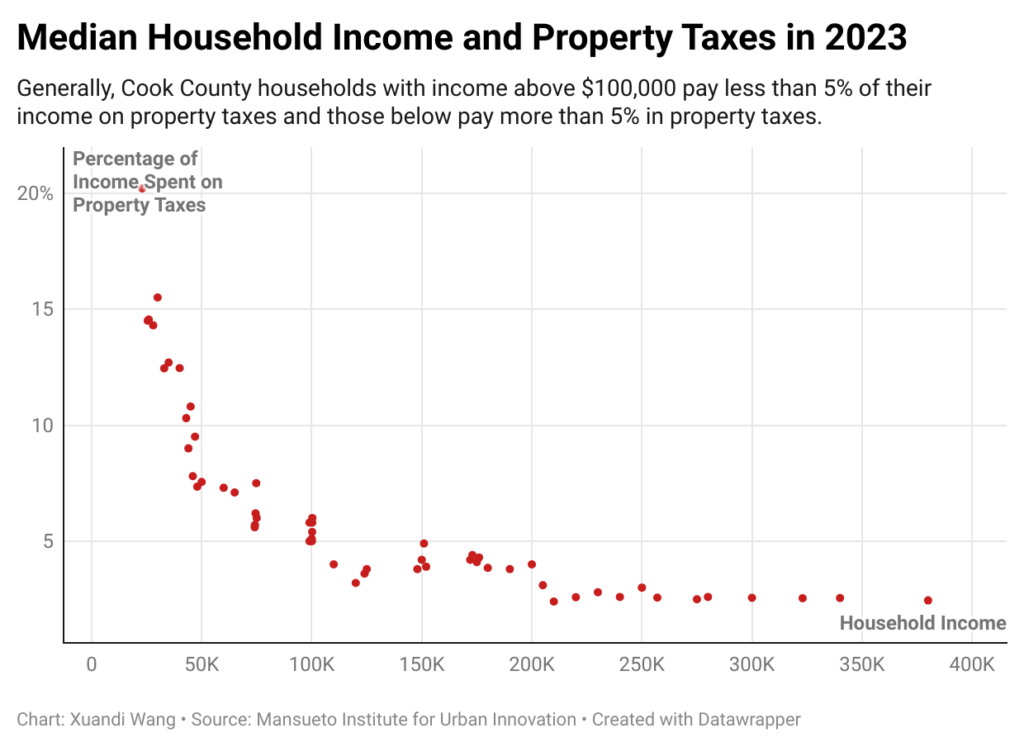

A 2024 study by the Center for Municipal Finance, a research group in the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy, found that higher-value properties are often undervalued, while lower-value properties are overvalued, creating a regressive tax structure that disproportionately burdens lower-income homeowners. The volatility of tax bills in gentrifying neighborhoods, where new construction and spiraling home values can price out longtime homeowners like Limas, compounds the problem.

Kaegi maintains that his office has made significant strides in improving the accuracy and fairness of property assessments. An analysis by Harris School professor Christopher Berry and the Government Finance Officers Association found that assessed property values have become more closely aligned with market values as Kaegi’s office has refined its financial models.

Increases in property taxes are driven by higher total levies imposed by cities to pay for services. But homeowners may end up paying a higher share of increases depending on how residential and commercial properties are reassessed year to year. The Sun-Times reported last week that as commercial properties downtown have been reassessed at lower values to account for higher vacancy rates, that’s shifted more of the tax burden onto residential properties.

Another possible reason the tax burden is shifted to homeowners could be a difference in how the Assessor’s Office and the Board of Review value properties. In 2022 and 2023, the Board of Review reduced the assessed value of commercial properties at a higher rate than residential ones.

In 2023, the Board cut the assessed value of commercial and industrial properties in the south and southwest suburbs by more than 21%, while reducing the assessed value of residential properties under appeal by only 4.4%. The previous year, the Board lowered commercial assessments in the north and northwest suburbs by nearly 20%, while residential values dropped by less than 2%.

“There still seems to be a gap between market value for commercial properties as they transact in the market and the values that are coming out of the board,” Kaegi said in an interview with the Weekly. “The most important thing that can be done right now [is to] make sure that we have a full reflection of the commercial values in the property tax bases.”

A spokesperson for the Board of Review declined an interview request. In a 2024 interview with ABC7 Chicago, Commissioner Samantha Steele (2nd District) defended the Board’s reductions in commercial assessments, arguing that the Assessor’s Office “inappropriately” raises commercial property values. Kaegi’s office did not respond to requests for comment on Steele’s claim.

In November, Cook County passed a $15 million homeowner relief program that is funded by interest fees from late property tax payments. The one-time program will provide direct payments to lower- and middle-income homeowners, though specific eligibility criteria has yet to be finalized, according to Gainer.

For a more lasting solution, Kaegi worked with state legislators to introduce a “circuit breaker” property tax relief program in the 2025 legislative session. Under the proposal, homeowners earning below a certain income threshold would qualify for relief if their property tax bills increased by 25% or more within three years. Eligible homeowners would see up to half of their tax spike covered under the plan.

“We know in Cook County there are communities that have high tax rates where you can buy homes at low prices,” Kaegi said. “But people don’t have a choice when prices are suddenly rising after they’ve bought their home, or the tax base is shifting after they bought their home, and suddenly you have a bill increase that you have to pay in thirty days.”

Circuit breaker programs are already in place in twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia. Illinois has previously implemented a similar measure for senior citizens, though efforts to expand relief have faced political and fiscal hurdles.

Kaegi acknowledged the challenges of pushing the measure forward, particularly given Illinois’ tight fiscal outlook for the upcoming year due to spiking healthcare and pension costs. Still, he expressed confidence that the proposal is gaining traction.

“This is the ultimate kitchen-table issue. This is the roof over your head. This is the potential risk of losing your home,” he said. “These are the kinds of things that keep people up at night, that generate anxiety, that can really shatter people’s finances in their communities.”

Xuandi Wang is a journalist and policy researcher whose writing has appeared in Block Club, the Chicago Reader, In These Times, and elsewhere.