When I first began working in a legal dispensary, I was excited to finally have my foot in the door in an industry that I actually cared about. Given how long it had operated underground, if there were ever to be an industry set up so that it’s run by the people for the people, I imagined, it would be cannabis.

While I knew that the Illinois cannabis market was a few steps behind in pricing and quality compared to other states, and that large cannabis corporations had the lion’s share of the market, I figured since it’s still such a new industry, there would be room to grow and I could do my part in being the change I wanted to see.

When Illinois legalized recreational cannabis in 2020, it could have been a sea change to the decades of disinvestment and injustices wrought by the war on drugs. Upon signing the Cannabis and Tax Regulation Act (CRTA) into law, Gov. J.B. Pritzker promised millions in low-interest loans for social equity licensees as a means of providing industry access to Black and Latinx entrepreneurs whose communities were most impacted by criminalization.

Yet just six months into Illinois’s first year of recreational cannabis sales, Grown In reported in 2020 that 77 percent of the state’s cultivation market was already controlled by just six major companies: Verano, Cresco, GTI, Ascend Wellness Holdings, Pharmacann, and Revolution Global.

Fast forward to 2024, and that hasn’t changed much. While there are now some craft-grown products in dispensaries, only thirteen of eighty-eight craft cannabis growers—essentially cultivators that operate on a significantly smaller scale than their counterparts—who obtained licenses since 2021 have become operational.

The market is still overwhelmingly dominated by a handful of corporations, many of whom lobby through the Cannabis Business Association of Illinois (CBAI) for legislation that favors bigger operations, such as limited canopy space for craft growers and anti-home grow laws.

Michael Malcolm, a medical cannabis patient, consultant, and applicant for the state’s social-equity license for retail dispensaries, said that when the CRTA was passed, he thought that the the legislation would heavily favor these corporate multi-state operators, some of which got a five- to six-year year head start in the medical cannabis market. It appears he wasn’t wrong.

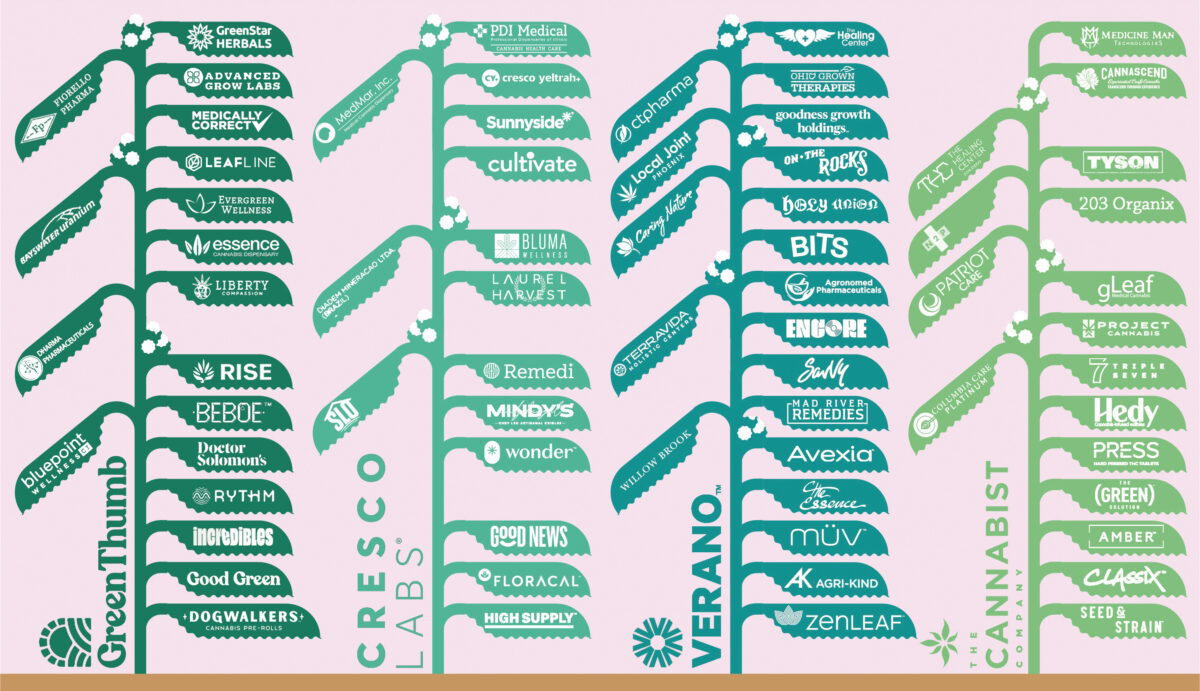

Multi-state operators (MSOs) are typically parent companies that own vertically integrated cannabis cultivation centers, processing facilities, and retail stores within each of several states. They cannot transport cannabis across state lines, but can operate in multiple states using the same branding and intellectual property. Curaleaf, which has 147 retail locations in seventeen states, is the country’s largest MSO; others include Green Thumb Industries, Cresco, and Verano.

The 2020 CRTA made retail licenses available to vendors several months before transportation and cultivation licenses were issued, making it so that independent retail licensees had to rely on MSOs for product, Malcolm said.

“The state was making it so that the retailers were going to be dependent on the corporate MSO companies that were already licensed in the state,” he said. “Let’s say I had won my [vendor] license. I wouldn’t have anything to put in the store since the only [cultivators] that can legally sell in stores were the corporate cannabis companies that were already operating, and those companies also already have retail stores. So they have no incentive to cut you in at a fair price.”

During the application process, Malcolm also learned that the state put certain requirements on the MSOs for them to help social equity-eligible applicants through a variety of different options, including as a partner to actually apply for more licenses.

Considering there would be no craft cultivators operating by the time he would have received a retail license, this route more or less pressures applicants to make a decision; either play by their rules in exchange for access to funds and resources, or burn money in trying to maintain independence.

“I saw that would be my best option if I was going to apply in the Illinois market, because at least if I had [a store], now my corporate partner who is already licensed with a cultivation license, has the supply that can supply my store, and they have to actually cut me a fair price, because I’m their partner,” he said. “If I’m not their partner, then I know this is going to crush me. And even if I somehow were to maybe even get a partner with a small cultivator years later, [MSOs] would still have so much of a supply they would always be able to undercut me and sell their own product at a better pricing.”

According to a 2021 Grown In report, from the time the CRTA was passed in mid-2019 through March 2020, vertically integrated companies reported a 292 percent production increase while cutting their total sales to independent dispensaries from 86 percent to 72 percent.

Cole Preston, a long-time consumer and medical patient in Illinois, said the current monopolization of the Illinois cannabis market was done by design. Preston runs Cole Memo (formerly Chillinois Podcast), a platform where he regularly interviews members from all levels of the Illinois market, from grassroots organizers and policy makers to the CEOs of MSOs themselves.

“The prices are so high that it’s just a tough shopping experience. Typically as a consumer, we welcome price compression,” he said. “A market comes online and it’s expensive right now, but [we assume] it’s going to level out, right?”

But that hasn’t happened in Illinois’s cannabis market, which Preston attributes to a specific policy choice made by the state to limit the number of licenses awarded.

Speaking at a 2021 event celebrating the opening of Ivy Hall in Wicker Park—a social equity dispensary that’s partnered with Verano—Pritzker said, “There are other states that have opened up the number of licenses to hundreds and hundreds of licensees and they have more dispensaries open than we do. But the reality is we’ve limited the number of licensees in part because we wanted to make sure that the social equity licensees had a fair shot in the industry and that they won’t be edged out until the very end by having too many dispensaries in the market so that people can’t make money.”

Despite, in theory, being for the benefit of social equity applicants, most of the industry in Illinois is dominated by MSOs, who benefit from the smaller number of licenses. “In other words, high pricing is a feature, not a flaw, from the business side,” Preston said.

Other factors inherent to making it in the cannabis industry make it easier for larger corporations with more capital to succeed. Application and license fees can run in the tens of thousands of dollars, and with cannabis being federally illegal, it limits the financing options for smaller companies.

GTI CEO Ben Kovler, whose company owns popular brands like Rhythm, Dogwalkers, and Incredibles, has publicly said that these laws and limited licensing create a “moat” around companies like his, protecting their profits from smaller competitors.

Preston isn’t the only one who thinks there’s a monopolization problem in Illinois. In 2022, an antitrust lawsuit brought by a group called True Social Equity in Cannabis alleged the state’s cannabis market being controlled by a “Chicago Cartel” that includes GTI’s Kovler as well as Akerna, a cannabis software company with ties to the Pritzker family, as Nicholas Pritzker is named as one of the owners

Jordan Melendez, a board member of the Illinois Independent Craft Growers Association and advocate with the South and West Coalition for Commerce and the Cannabis Equity Illinois Coalition, said he thinks Illinois isn’t achieving true cannabis equity for several reasons. The reasons will vary depending on what type of license one owns, but he said one issue that seems to affect everyone is simply a lack of financial support from the government.

“For me, true social equity is how much of the market share [craft growers] have, not the amount of quote-unquote social equity licensees,” he says. “But…what is ‘social equity’ in the first place? The letter of the law says it’s supposed to reverse the harm due to disproportionately impacted areas from the war on drugs.”

But exactly how is Illinois reversing those harms? According to Melendez, there is a lack of transparency from the state regarding when and just how many funds will be dispersed. So far, of the 185 original first-round social equity licensees, only thirty-three have received loans from the state according to DCEO, with only one second-round licensee, Grand Legacy, LLC, receiving funds.

Illinois also only allows a maximum canopy space of 14,000 square feet for craft growers to cultivate cannabis versus 210,000 square feet for cultivation centers owned by MSOs.

Even that was a recent change made in December, when the previous cap on craft growers was 5,000 square feet. Other than craft growers, only medical patients can grow cannabis in their homes, and they can only grow a maximum of five plants.

Largely as a result of such laws, consumers primarily spend their money in dispensaries and on brands owned by MSOs.

“The current big boys don’t want other big boys in the game,” Melendez said. “You think they want another out-of-state player that has enough money to build a whole $100 million facility? No, they only want craft growers to grow out of 14,000 square feet.”

There are currently twenty-two licensed cultivation centers in Illinois, and thirteen craft growers that are in operation. Melendez posits looking at market share not just by how much money is being made from individual companies, but also looking at the actual canopy space that’s owned by cultivators. He rattled off numbers to illustrate the point.

“Eighty-eight craft grow licensees times 5,000 square feet is 440,000 total square feet of canopy space. There are twenty-two current cultivation center licenses, multiplied by the 210,000 square-foot limit, that’s 4,620,000 square feet,” he said, or about 90 percent of the market share by canopy space.

“Stark, stark variance and that’s only assuming all craft grow licensees are operational and using [all] 5,000 square feet of canopy space,” he added.

What can Illinois cannabis consumers do to advocate for a more balanced playing field for social equity licensees? Being intentional about spending money with fully independent craft grow operations and joining organizations like Chicago NORML or the Illinois Cannabis Equity Coalition can help.

But Melendez said that getting regular consumers to care remains a challenge.

“That’s always gonna be the question, but the thing is they don’t [care],” he said. “Cannabis is still a niche…billion-dollar industry in Illinois alone, but it’s still a niche industry itself.”

Will that change? “That’s up to the people,” Melendez said. “It’s always been up to the people.”

Alejandro Hernandez is a freelance writer born and raised in Chicago. Growing up in the city gave him the sense of perspective that can be found in his work. With combined experience doing broadcast and written journalism, Alejandro has been actively documenting the stories of everyday Chicagoans for over seven years.

I was wondering why I always see the same products at Chicago dispensaries no matter where I go. Thank for this reporting!

I own, apparently, an extremely extremely small company by comparison called the Culinary Cannabis Company or CulinaryCannaCo. And it is BRUTAL out there. You’re right. No one seems to care and to be fair with all the brands you never know who you are supporting. Your graphic is superb. I’d love to see this article updated to 2026 as everything seems to be shifting. Regardless, this was an excellent read back in the day and so good that years later in February 2026, I remembered that graphic and referred to it. Truly nice work. And if it gets updated, I’d love to see that. Actually, what would be really nice would be if you did an article about the rest of us. There can’t be that many left. We are trying… It’s all I can say. We are chasing a dream and doing the best we can.