Maria Hinojosa’s memoir, Once I was You: A Memoir of Love and Hate in a Torn America, is like a time capsule: it spans historical events during the turbulent 1960s and 1970s until the current events of the 2020s. The book analyzes America’s attitude towards immigrants throughout the decades and Hinojosa narrates her life from the time she entered the U.S. as a child, and her life as a teenager and young adult. It is the memoir’s personal stories that connect the dots of what it truly means to be an immigrant in America.

Hinojosa peels back the layers of America, writing “our attitudes toward the immigrants who come here to work, either by choice or force, are double-edged.” History is written by the winners, and America is no exception. She breaks down the words behind the Declaration of Independence as it mostly applied to white men, and examines the white-washing of the first settlers.

“History shows us the truth,” Hinojosa writes, “Or rather, one version of U.S. history told from a limited perspective reiterates the ‘truth’ that they want us to believe.” Even the Transatlantic Slave Trade, justified as the driving force behind America’s economy, is written from the “perspective of white male privilege” as it rather should be called a “government-sponsored human-trafficking ring” instead, she writes.

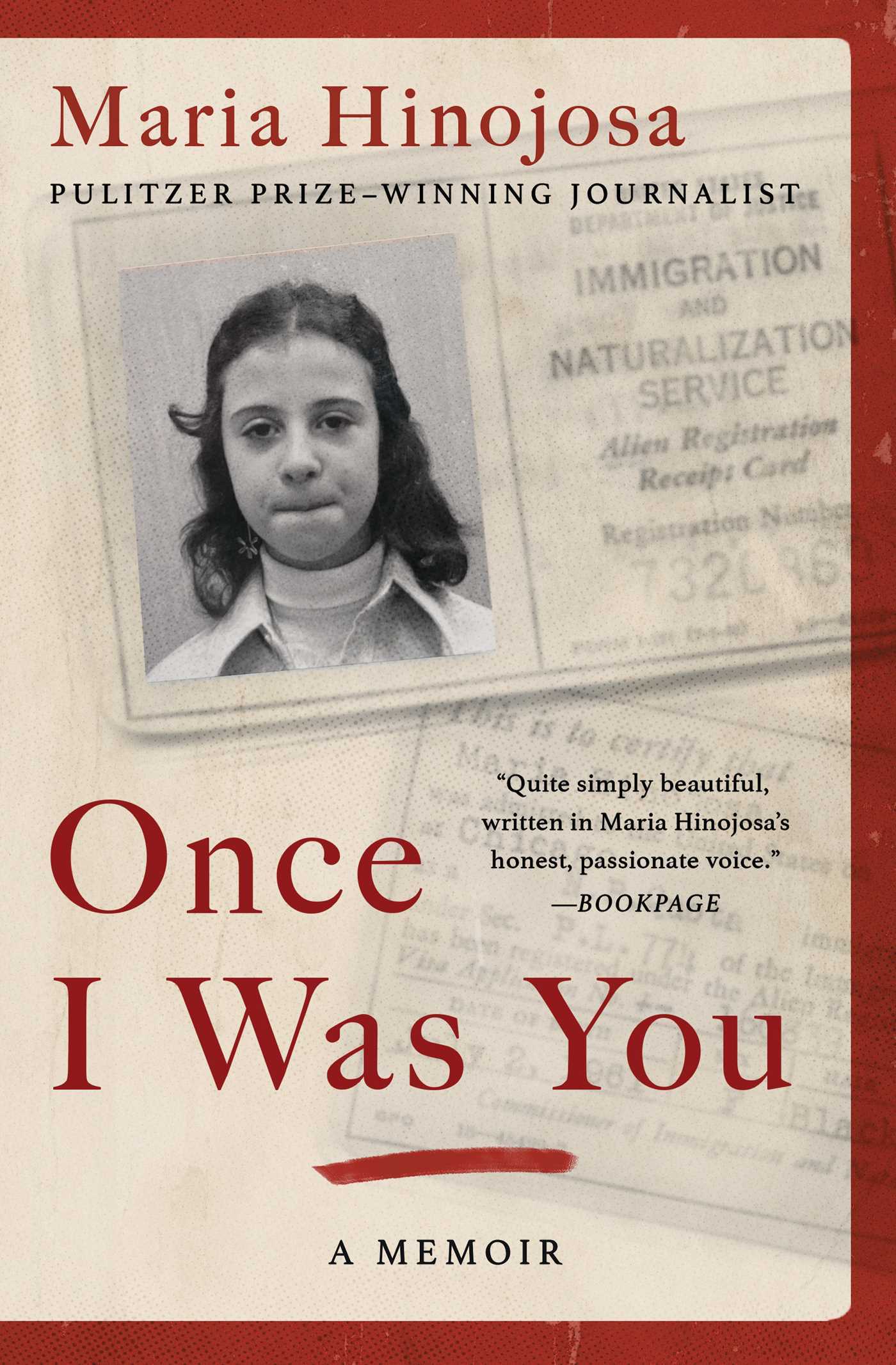

What does it mean to be American? Hinojosa was born in Mexico City in 1961. Her father, Dr. Raúl Hinojosa, MD, was selected by the University of Chicago to continue his research on the temporal bone at their institution. Hinojosa understands that her family’s immigration to the U.S. was only made possible through her father’s career journey as Raúl was required to become a US citizen in order to work with U of C. “My dad was part of the opening of this country toward some immigrants,” she writes. Hinojosa knows this isn’t your average immigrant story.

Dr. Hinojosa didn’t understand his family’s place in America’s racial dysfunction—was he white or colored? Originally from Tampico, her father was a small-town man overwhelmed by this new world. There were signs that read “No dogs, Irish or Mexicans” dictating who could use the drinking fountain based on whether you were white or Negro. Working at U of C was his dream job but “not in his dream country.” Where did the Hinojosas fit in America?

Her mother and siblings immigrated to America in 1962, obtaining green cards or permanent residency cards, which granted them legal residency and work authorization while also being able to keep their Mexican Citizenship. They joined Raúl and settled in Hyde Park but, unlike other immigrants, Hinojosa was still able to experience her birthplace – her family would often visit Mexico City every summer. She describes it as “a beautiful product of the chaos of confrontation between the advanced civilizations of the Mayans and Aztecs clashing with the arrivals of the Spaniards…a multicultural puzzle.”

The idea that race plays a role in achieving the American Dream is not lost upon Hinojosa. She touches upon the racial dynamics in America, and the dichotomy of the “good immigrant and bad immigrant” based on America’s economic growth. When the country is doing well, immigrants are seen as hardworking, but on the other side of the coin, immigrants are used as scapegoats during economic downturns.

Describing her family, she writes, “We were not Americans, but if we kept our mouths shut, sometimes we might be able to pass.” There is a racial hierarchy and to be accepted as an American is to gain a degree of whiteness. Hinojosa understands that she could pass as white in different contexts and has privilege that was “hard-won.” While she doesn’t go into more detail, only writing, “whiteness became an unspoken privilege that always felt like it should have never been ours,” at the end of the day, she didn’t feel like she could fit into America’s standards or even Mexico’s.

“The first years of my life had been here in the United States, in Chicago, with gray skies, frigid winters, caves and hills made of ice, steamy humid summers, black people, and Motown,” she writes about growing up in Hyde Park. “Not Mexico City, with palm trees and the Popocatépetl, sweet vendors, and my tias, tios and primos.”

During her teenage years, Hinojosa has arguments with her boyfriend as he attempts to tell her that she’s American—“You’re really American! Why can’t you just say so?” Hinojosa’s journey to finding her voice is also based on her bi-nationality as she writes, “being binational required constant jujitsu to navigate the expectations of others, and it was exhausting.”

But throughout the memoir, she expresses the importance of community and family to understanding herself and creating the pathway towards her journalism career. During her time studying at Barnard College in New York in the 1980s, she was a student activist and created her own community of counterculture disruptors, queer radicals, feminist revolutionaries, war refugees and everything in between.

She got her footing as a radio host at WKCR during Barnard and since then, Hinojosa has covered ICE raids, abuse in detention centers, youth violence, DACA, and more; she has reported for PBS, CBS, WNBC, CNN, and NPR. Recently, Hinojosa was featured in the Sor Juana Festival at the Museum of Mexican Art in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago. The festival celebrates the legacy of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, a 17th-century Mexican nun who fought for a woman’s right to education, and pays tribute to the accomplishments of Mexican women “from both sides of the border.”

Hinojosa continues to bring attention to perspectives that are underreported in mainstream media. She writes, “I am that Mexican immigrant who is always looking for others like me everywhere, searching for visibility in others.”

As a daughter of Congolese immigrants, I resonated with Hinojosa’s experiences as the “grateful immigrant,” the exclusive club of “having moms and dads who spoke with thick accents,” and watching 60 Minutes as a family during dinner. It’s important to not only shine a light on the issues that we as a country prefer to keep hidden but to also humanize the people behind the stories. As a reporter, Hinojosa has succeeded in uplifting the voices beyond the headlines and her memoir is no different.

Once I Was You is a beautifully written memoir that often reads like literary fiction. Each page flows into the next as the memoir spans her childhood to adulthood. The memoir captures the differences of her two homes: “crazy, colorful, tormented yet loving” Mexico City and “grayish-blue skies and trees that change color” South Side Chicago.

In some moments, Hinojosa romanticized her time in college, and did not delve enough into discrimination based on skin tone, as she only briefly mentions her parents’ distrust of Black Americans or the fact that Hinojosa is of lighter complexion and, at times, could pass. While Hinojosa did not address these in-depth, Once I Was You is still an insightful read that rings more true as the country continues to swim in racial tension.

Until Americans address the skeletons in their closet, we will continue to be a nation divided and full of broken promises. “If you can’t take this color, then maybe you can’t take us,” Hinojosa writes.

Sarah Luyengi earned her B.A. in English with a concentration in creative writing from the University of Illinois at Chicago in 2014. Some of her non-fictional work has appeared in Borderless Magazine. She last conducted a Q&A with Beverly Artist Hollie Davis.