On December 30, Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced that the Chicago Police Department will add an additional seven hundred Tasers to the force by June of this year, bringing the CPD’s number of stun guns to fourteen hundred. Officers will also be trained in de-escalation tactics that emphasize nonviolent confrontation methods. This announcement comes after weeks of intense criticism of the police department, the city government, and Emanuel himself after the video of Laquan McDonald being shot by Officer Jason Van Dyke was released to the public in November.

Part of the impetus for this expansion of Tasers comes from the fact that officers involved in the McDonald shooting had requested that a Taser be brought to the scene. This request was never fulfilled, leading to speculation about what might have happened had the officers had access to such a device.

The hope behind this move by the CPD seems to stem from an assumption that officers would use Tasers instead of firearms in tense situations, thus preventing shooting deaths while allowing officers to exert control over suspects or detainees. Acting superintendent John Escalante, who took over following Garry McCarthy’s recent firing, said that additional training should emphasize such methods.

“We expect that every police officer develops skills and abilities that allow them to help dissolve confrontations by using the least amount of physical or lethal force,” he said at a press conference December 30. “There’s a difference between whether someone can use a gun and when they should use a gun.”

The use of Tasers by police departments in the United States has risen rapidly over the last fifteen years. In 2000, only about seven percent of departments used the weapons, but by 2015 this number had risen to eighty percent, according to the Department of Justice. Taser International, the manufacturer of the eponymous stun guns, claims that their products have “saved more than 155,000 people,” and maintains that Tasers are safer alternatives to live guns. Taser International has also begun concentrating efforts on manufacturing body cameras and marketing them to police departments as a way for police officers to tell “their side of the story,” as reported by Harper’s magazine. These body cameras have recently become the focus of a national debate about solutions to police brutality, and have been endorsed by advocates of reform in Chicago and elsewhere. This year, in addition to Tasers, the CPD will be broadening its use of body cameras and dash-cams in six of its police districts.

But despite Taser’s assertions and investment in other police reform mechanisms, the reality of Taser safety is complex. According to a study conducted by the National Institute of Justice, a standard five- to fifteen-second Taser shock does not pose significant long-term health risks when tested in a controlled environment, with subjects who are calm and in good health. However, according to Amnesty International, repeated or longer shocks can produce adverse and potentially deadly affects, and even single shocks can produce lethal results in people who are under the influence of substances, are not in proper health, or whose bodies are in “fight or flight” mode. In a 2012 study published by the medical journal Circulation, shots to the chest are especially dangerous and can cause cardiac arrest. Amnesty International concluded in the aforementioned study that police had killed over five hundred people with Tasers since 2001.

The timing of this announcement from the CPD is even more curious given the December release of another police video, this time from 2012, depicting mentally ill man Philip Coleman being repeatedly shocked with a Taser by Chicago police officers in his jail cell. Coleman died of his injuries the following day. The incident, which has elicited considerable criticism, occurred just after Chicago increased its Taser arsenal for the first time in 2011, during a period when CPD Taser use (predictably) skyrocketed.

As for the effectiveness of Tasers in reducing deaths and injuries, a Department of Justice study of several police departments found that Tasers can lead to fewer officer and suspect injuries than pepper spray, batons, or bodily force. A 2009 study by the Police Executive Research Forum found that injuries to police officers decrease by seventy-six percent when the officers use Tasers. However, Tasers have continued to appear in high-profile cases of police brutality, which suggests that rather than using Tasers as an alternative to lethal force, often police officers in Chicago and across the country have used Tasers in situations that may not have required any force at all, unnecessarily escalating routine encounters like traffic stops. Sandra Bland, who infamously died in police custody last year, was threatened with a Taser during a traffic stop, and in 2014 two Hammond, Indiana police officers were investigated by the Department of Justice for firing a Taser at a woman inside her car during a stop.

What’s more, a 2009 study on the impact of stun weapons from the University of California San Francisco Medical Center found that the introduction of Tasers in California police departments increased sudden deaths and could have increased police shootings by escalating confrontations. This complicates the narrative presented by the CPD and Taser International, which presents Tasers as a lesser evil that can be used to prevent more grievous acts of violence.

An analysis done by the Chicago Tribune in 2012 just after the 2011 Taser expansion found that Taser use jumped from 197 uses in 2009 to 857 in 2011, but shootings by police did not significantly decrease. While there were 114 shootings in 2009 and 109 in 2011, the number of shots that reached their target actually increased from 56 in 2009 to 58 in 2011.

From 2010 to 2015, Chicago police have fatally shot 70 people, more than any other police department in the country, despite the introduction of Tasers in 2011.

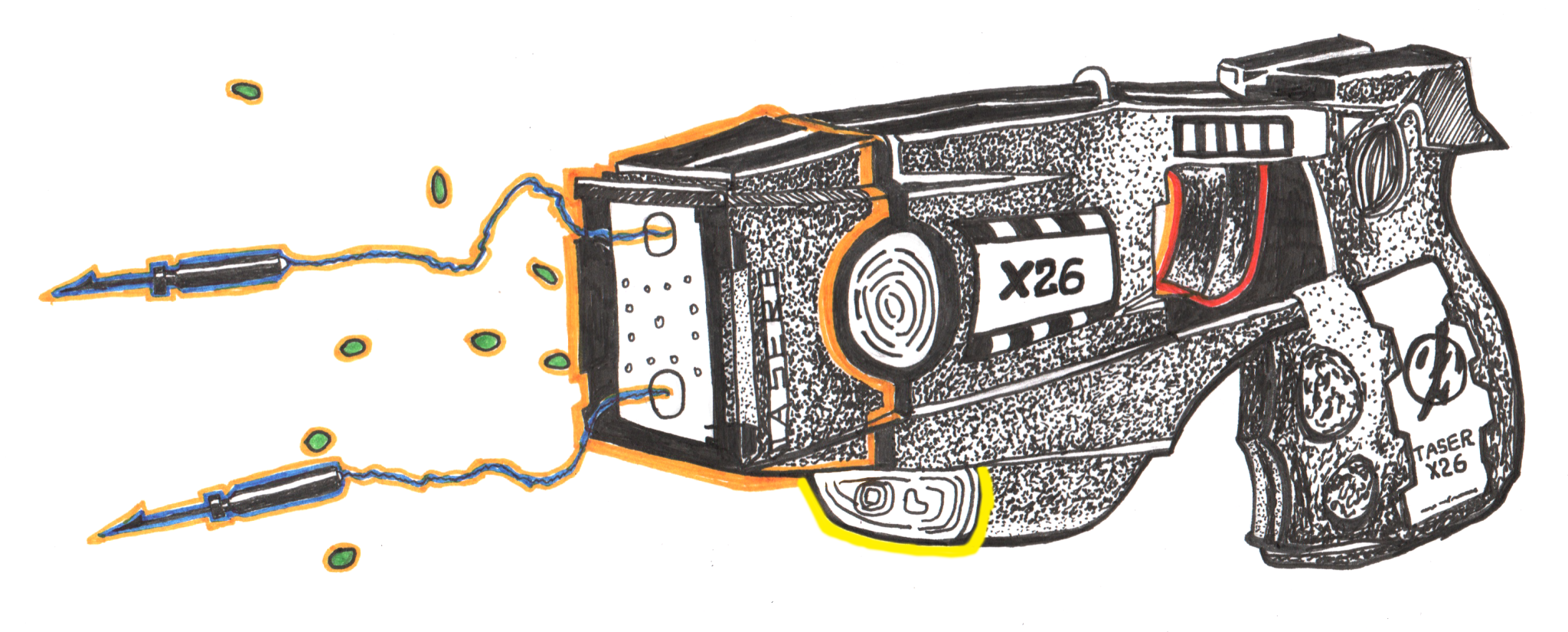

The X26

Illustration by Julie Xu

Color coded annotations by Jake Bittle

Taser International only manufactures a few models of Taser; the X26 is by far the most popular among police departments and civilians. The “X26c” model, available for purchase by the public, has a smaller voltage and a smaller probe range.

Like a gun, the Taser is fired by aiming down the sights and pulling a trigger. The battery on the X26, located at the rear of the weapon, contains enough charge for about three hundred shots, but the probes can only be discharged once or twice before a reload is necessary.

These probes travel up to thirty-five feet and penetrate a subject’s clothing, establishing a conductor for the electrical charge. This is how Tasers differ from normal “stun guns”: they don’t need direct contact in order to shock their target. (But it’s also possible to shock someone without the probes by driving the Taser directly into their body.) In cases where the target is wearing heavy clothing, however, the probes are often unable to penetrate far enough.

Once the probes make contact, the Taser releases an electric charge that travels down the parallel line created by the probes and enters the target’s body. The charge begins at fifty thousand volts (a normal electrical outlet is about a hundred volts) but decreases substantially by the time it reaches the target’s body.

In an accountability feature that foreshadows Taser International’s later development of police body cameras, the Taser releases tiny discs that record the serial number of the weapon in order to create a record of how and where the weapon was used.

The X26 model comes equipped with an LED flashlight and a laser pointer that indicates where the probes are aimed.

The charge can have different effect depending on the size, health, and clothing of the target, but in general it shuts down the body’s neuromuscular systems. This effectively paralyzes the target for up to thirty seconds. Contrary to popular belief, the charge is not designed to cause the target pain, but rather to contract the target’s muscles and prevent him or her from escaping or attacking.

Having read this I thought it was rather enlightening.

I appreciate you finding the time and energy to put this article together.

I once again find myself spending a lot of time both reading and leaving comments.

But so what, it was still worth it!