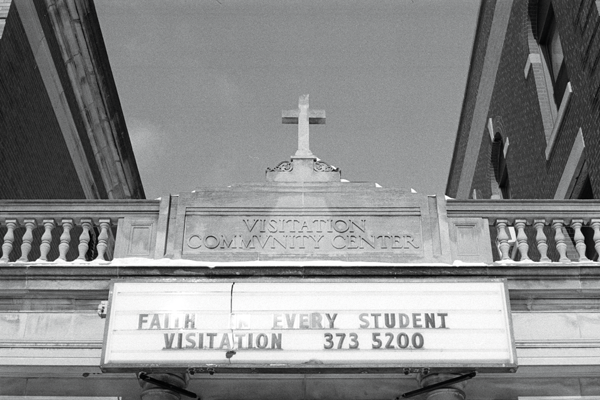

The sisters welcomed me into Visitation Catholic School’s beautiful sunken lobby, their smiles illuminated in the late-morning light. They positioned me before an elaborate illustration memorializing the school, one of Englewood’s two remaining Catholic grade schools, and joked about the routine nature of their upcoming lesson on the school’s history. Their laughter reverberated from the high ceilings and original tile work of the nearly hundred-year-old room, the first of many outbursts to echo from Visitation’s walls.

Englewood has faced a dwindling school-aged population in the last fifty years. A study from the Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago detailed the declining population trends for Englewood’s seventeen-and-under age bracket, finding that population figures for minors fell by fifty-one percent from 1990 to 2010, with a thirty-two percent decrease between 2006 and 2010 alone.

Since 2012, Englewood and West Englewood have faced seven closures in Chicago Public Schools. In addition, sixty-eight percent of its children were living in poverty in 2005 according to the Chapin report. This percentage has decreased over the past twenty years, but the change is primarily due to Englewood’s overall population decreases rather than economic improvements.

As the sisters and I meandered through the beautifully-preserved, spacious hallways of Visitation, we passed by a group of elementary school children, gently led to their destination by a smiling teacher. We stopped to say hello, and all fifteen young faces acknowledged us warmly.

“Say hello to our visitors,” said Sister Jean Matijosaitis, the principal of Visitation, eliciting a lackluster “hello” from the boys.

One boisterous student proclaimed his approaching birthday, and we all shared in his happiness with laughter and high-fives.

“How old are you now?”

“Eleven!”

In Englewood, and all over Chicago, CPS closures have left families with even fewer options for an affordable education. Catholic schools have been affected by budget cuts as well. This past December, the Stewart campus of the Academy of St. Benedict the African (a fellow Englewood Catholic school) was closed due to insufficient funding for vital repairs to its heat infrastructure.

To assist their families, the St. Benedict campuses on Stewart and Laflin Streets, as well as Visitation, offer scholarships to students through the Big Shoulders Fund, a Chicago-based organization aimed at providing financial aid for Catholic school students in the city’s most economically depressed areas, including enrollment into the federal free and reduced lunch program. In addition, both Visitation and St. Benedict-Laflin stay open from 6am to 6pm, complete with before- and after-school free and paid programs.

St. Benedict, formally known as St. Bernard, closed in 1980 as the neighborhood transitioned and lost much of its Catholic population. However, the school quickly reopened with a new name, Academy of St. Benedict the African, in recognition of a new demographic of potential students. When St. Benedict’s Stewart campus, located at Stewart and 65th Street, closed last December, about thirty of St. Benedict’s students transferred to Visitation, adding an entire kindergarten class to the school’s population.

Other Chicago institutions have also lent their support to Visitation, solidifying the school’s historic leadership position within the Englewood neighborhood. DePaul University regularly sends students to tutor Visitation kids, especially within the arts department.

Matijosaitis continued leading me through the school, through several doorways and up stairwells before revealing an intricate mural piece by DePaul students on the stage of the auditorium. Traces of support networks like DePaul’s art and tutoring program run throughout the school building, supporting Visitation with the vital backing that keeps it operational.

Our trip soon brought us down several stairs into the school’s basement. As we approached the gymnasium, screeches of unhindered glee pierced through the darkness; a cavalcade of four-year-olds locked in serious games of childhood splendor filled the room.

“They’re just three and four, but they’re completely a part of our school community,” said Sister Diane Boutet, Visitation’s development director. “They participate in everything; if we have an assembly, they come, if we go over to church, they come with us.”

This sense of inclusion adopted by institutions such as Visitation is perhaps the key to their success, especially among minority populations. Charles Payne, a professor at the UofC’s School of Social Services Administration, recently spoke about how Catholic schools tend to do well with minority students. He discussed the ability of Catholic schools to place emphasis on moral inclusion, instilling within their students a sense of purpose and the belief that they are welcome regardless of their circumstances. He described Catholic schools’ attitude as one of admission: “Whatever you are, you are one of us.”

Catholic schools such as Visitation serve as another option amid the scant availability of schools in Englewood. Many neighborhood public schools, the ones that remain open, are unsatisfactory for some parents, and placement into a charter school is not guaranteed. Kim Robinson, a receptionist and parent of three Visitation students, said, “There’s a lot of politics in public school, and [in] Catholic school there isn’t. And I’m not saying that Catholic school is all it’s cracked up to be, but at the same time, it works for me.”