A crowd gathered in Daley plaza on August 15, 1967 to witness the unveiling of the “Chicago Picasso.” The installment was an unprecedented one—up until then, Chicago public sculptures had mostly taken the form of commemorative statues. The “Picasso” would signify a new direction for Chicago city art away from the commemorative style. Later installments like “Cloud Gate,” which are now entrenched parts of the downtown landscape, exemplified this artistic shift.

Twelve days after the “Chicago Picasso,” a different gathering took place on the South Side of Chicago. It was a celebration around the recently completed Wall of Respect at 43rd Street and Langley Avenue. The Wall was unprecedented for its own reasons: its theme of “Black Heroes” (Malcolm X, Muhammed Ali, and Marcus Garvey, to name a few) made it a rare piece of public art that celebrated African-American culture and resistance movements. A fire in the TV repair shop next door partially destroyed the mural in 1971, which gave the city leeway to pursue its redevelopment plan for the area and raze the building containing the mural. But the effects of the Wall were more permanent: the mural inspired similar community-driven murals and art projects in cities across the country.

1967 was an important year for public art in Chicago. The legacy of the “Wall of Respect” and the “Picasso” is in particular relief in 2017: Mayor Emanuel and the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE) have designated it the “Year of Public Art,” five decades after the two works’ unveiling.

“There are definitely some lessons to be learned from the “Picasso” and the “Wall of Respect” in shaping how we are endeavoring to do this massive project,” said Erin Harkey, projects administrator for DCASE, about the 50×50 Neighborhood Arts Project.

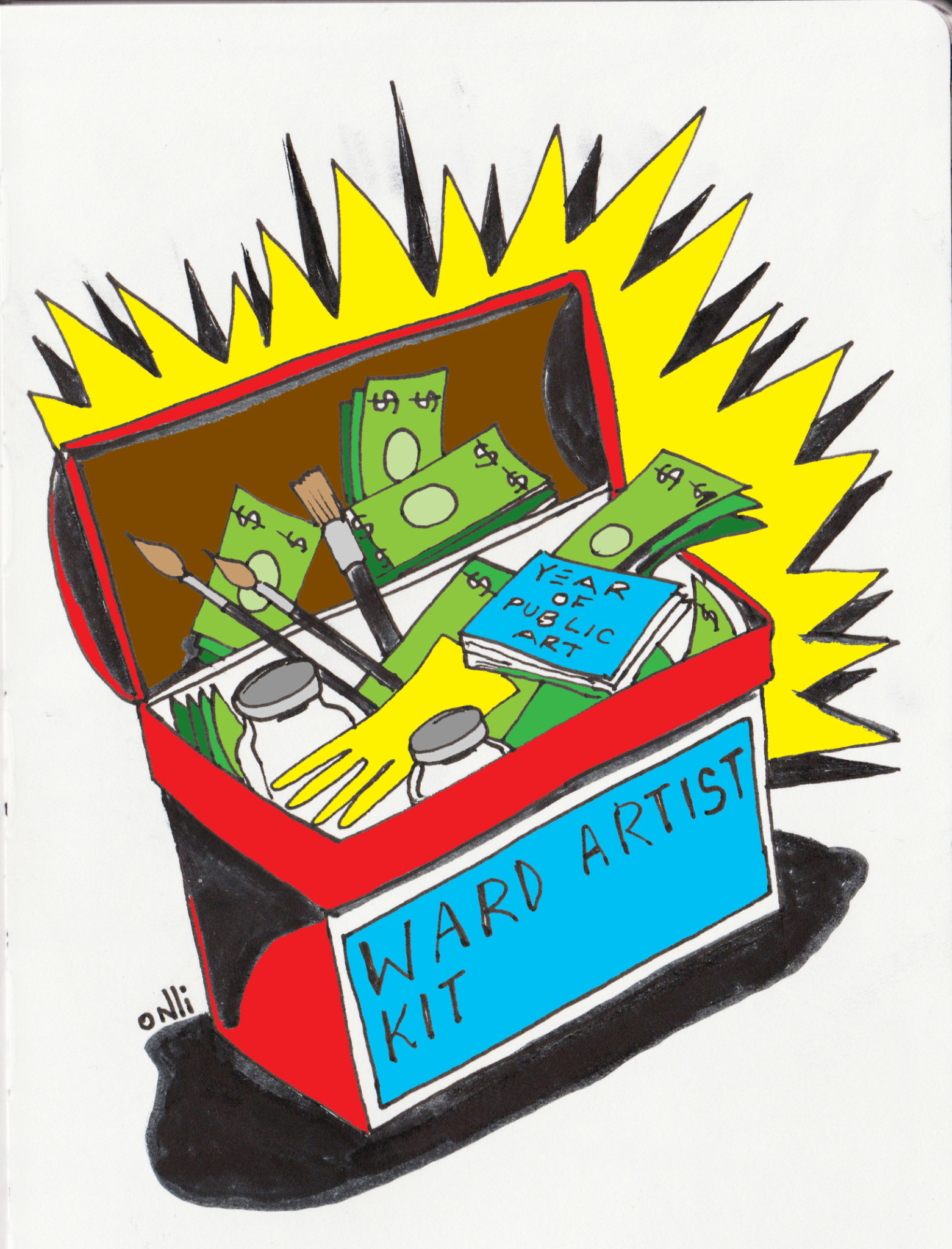

The 50×50 program—whose name alludes to the fiftieth anniversary of the two historic installments and the fifty Chicago wards—is an important facet of the City’s multipronged celebration of the anniversary. The celebration includes, among other things, a collaborative marketing campaign designed to facilitate cooperation between DCASE and other government agencies, the establishment of the Public Art Youth Corp, and a host of exhibitions at the Chicago Cultural Center.

Under the 50×50 Neighborhood Arts Project, DCASE and the mayor’s office incentivize all fifty of Chicago’s alderman offices to commissioning public art installations in their ward. The program allows aldermen to dedicate a portion of their 2017 menu allotment to commission public art; DCASE will match up to ten thousand dollars of that dedication. “It can’t just be a top down approach,” Harkey said. In that way, the program takes after both 1967 pieces: like the “Picasso,” the 50×50 program combines city and private grants in creating foundational public art. As with the “Wall of Respect,” the intention for the Neighborhood Arts Project is an intense focus on community identity, and engaging residents and engaging communities in the development of the art works.” The deadline for local artists to submit proposals is March 10.

The city of Chicago has history of commissioning public art, before and after 1967. According to DCASE’s Chicago Public Art Guide, the highest concentration of major public art installations is in the Loop, where there are fifty-one pieces. There are also thirty pieces on the North, Northwest, and Northeast Sides, eight on the West Side, and thirty-nine on the Near South, Southwest, and Southeast Sides. This list includes works not only in open spaces, but also some in city-owned facilities like libraries and CTA facilities. Much of this art was brought to Chicago via the Percent-for-Art program, initiated in 1978 by an ordinance which set aside 1.33 percent of the annual construction budget for the commission and acquisition of artwork.

But the 50×50 Neighborhood Arts Project is new for DCASE. If the agency succeeds in bringing installations to all fifty wards, that will increase by nearly forty percent the public art projects that exist in Chicago. As of now, thirty-eight of the fifty wards have confirmed their participation in the 50×50 program. A list of which wards comprise this thirty-eight is, at the moment, unavailable to the public. The nature of the program’s funding, in which alderman first have to set aside a portion of their 2017 menu allotment before the city will match it, may limit certain wards from participating due to their own budgetary constraints. Normally, aldermen use their menu allotments for infrastructure maintenance and improvements in their wards—like paving roads and fixing streetlights. At a budget hearing in 2015, Transportation Commissioner Rebekah Scheinfeld noted that the menu allotment couldn’t always “cover the needs in your wards annually,” as the Sun-Times reported.

Harkey said the city has taken this into account while creating the programs for the Year of Public Art. “It is our desire, and actually our mandate, to make sure something happens in all fifty wards,” Harkey said. “If the alderman has not opted into the 50×50 Neighborhood Arts Project, we are looking at a number of different ways to engage with all fifty wards.” The artist selection process is still underway, so it’s too early to tell which wards will require alternative assistance from the city government. Speaking broadly, Harkey said this assistance could take several forms: “It might be that we bring a performance to that ward, or we identify an arts organization that’s already working there, and we’re able to provide additional resources to help promote that event…so we’re still working out how we can supplement the 50×50 to make sure that we are reaching those wards, even if, for whatever reason, they are unable to contribute to have a neighborhood arts project.”

On a ward-by-ward basis, it’s hard to tell how the Year of Public Art Program will unfold, although DCASE is optimistic about including all fifty districts in some way or another. The city itself looks to use this as an opportunity to reformulate its relation to public art. “There’s both policy and strategy that needs to come out of this large investment this year,” Harkey said. She said that heavier collaboration between city agencies, aldermen’s offices, and community organizations is a part of that. “We’ve also engaged stakeholders in conversation about the development of the Chicago Public Arts plan,” a document slotted to come out sometime this summer, and which will chart the city’s engagement with public art in years to come. 2017 therefore looks to be as important a year as 1967 for Chicago public artworks from the standpoint of both policy and the actual commissioning of installations. The 50×50 program may serve as a litmus test as to whether this shift will be felt equally in all wards of the city, including those with little cash to spare.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.