Mayor Brandon Johnson’s plan to temporarily house asylum seekers in tent camps drew wide criticism last week, even as a surge in new arrivals nearly overwhelmed already crowded police stations.

On the morning of Friday October 1st, members of the public and alderpersons blasted the tent camp plan in a raucous hearing of the City Council Committee on Immigrant and Refugee Rights. That afternoon, about fifty people protested the plan in Daley Plaza. By the end of the week, progressive alderpersons had also trained their ire on Governor J.B. Pritzker after expressed concerns about the plan.

The one consensus in the plaza, City Hall, and the governor’s mansion was that President Biden and the federal government need to do much more to support asylum seekers.

Nine buses from Texas carrying about 500 asylum seekers arrived in Chicago on Friday, exacerbating an already dire situation. Earlier that day, the Office of Emergency Management and Communications alerted mutual aid volunteers that as of noon, there was no available space and asked if any police districts would be able to provide space. Over the weekend, fifteen more buses were expected.

Since last August, more than 15,000 asylum seekers have arrived in Chicago. As of last week, more than 9,000 were staying in the city’s shelter system, which the Johnson administration has rapidly expanded since taking office in May. Another 1,600 were sleeping in police stations, which have served as makeshift housing for those awaiting placement in shelters.

Retiring police stations as housing for migrants is the city’s number one priority, said Deputy Mayor for Immigrant, Migrant and Refugee Rights Beatriz Ponce de León at Friday’s meeting, and setting up base camps is one solution.

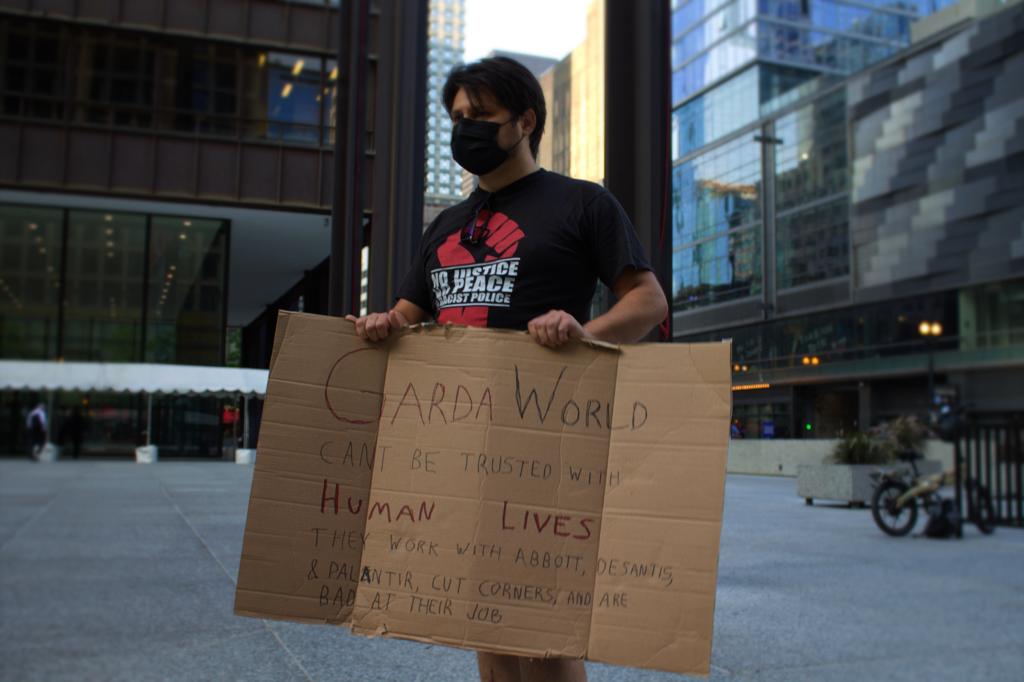

Much of the concern around the tent camps stems from the fact the city’s $29 million contract to set up and run them is with GardaWorld Federal Services, a multinational private security company. The public and alderpersons have expressed concern over GardaWorld’s involvement in migrant detention in Canada and contract with Gov. Ron DeSantis to fly migrants out of Florida, as well as the process of local procurement.

At the start of Friday’s committee meeting, Vasquez said he was “saddened by the possibility” that the Johnson administration was about to move forward with “building military-grade tent base camps” in Chicago. “The elected representative in me, on the other hand, recognizes that in order for us to be successful, we as a municipal government have to come together to move our city forward,” he added.

“There’s a reason not to rush government contracts,” said Ald. Scott Waguespack on Friday, referencing allegations that GardaWorld committed fraud on a federal contract in Georgia. “That’s a red flag.”

After the news broke on September 20 that the tent camp contract was with GardaWorld, multiple independent political organizations, including the 25th Ward IPO, 33rd Ward Working Families, and 40th Ward Workers United separately released statements last week blasting the decision and calling for the contract to be canceled, as did the Edgewater Mutual Aid Network and Rogers Park Food Not Bombs.

Antonio Gutierrez, a strategic coordinator at Organized Communities Against Deportations (OCAD), told the Weekly that because the plan is a temporary solution, they’re concerned about the long-term plan. “The crisis is not the recently arrived migrants, but the overall lack of affordable housing in the city of Chicago,” Gutierrez said. “We also don’t think that will be the best usage of these millions of dollars…that could otherwise be used in other ways to actually create permanent affordable housing.”

33rd Ward Working Families’ statement commended Johnson for working with limited resources to uphold Chicago’s commitment to being a Welcoming City. “Nobody wants to see asylum seekers on the floors of police stations,” it read. “But the potential that these structures prove inadequate and leave people to the mercy of private police and soldiers is no less troubling. If the administration earnestly believes these are the best available options, we call for radical transparency.”

The statement lists questions about the timeline to transition migrants from tents to “dignified housing,” the plan to prevent abuse of migrants by GardaWorld, what other options the city has, and what FEMA and the Biden administration can do to help. Several alderpersons echoed those questions at Friday’s meeting and requested more transparency.

Ald. Rodríguez Sánchez said she is “in constant conversation” with 33rd Ward Working Families, of which she was a rank-and-file member before it was instrumental in electing her to the City Council in 2019. The organization “did what they thought they needed to do in order to uphold the values that we have decided to stand on as it pertains to humanity. I think they did it very respectfully and they did it in a way that asks a lot of questions rather than pointing fingers.”

Rodríguez Sánchez said she’s committed to visiting the tent camps and periodically sleeping in them to make sure the conditions are up to standards. “We’re not hiring somebody and abandoning it,” she said. She added that her ward office has worked with mutual aid volunteers to ensure the temporary shelter at Brands Park in Avondale had regular needs assessments and that those needs are being met.

“I think standardizing that kind of protocol, including the mutual aid groups, including the CBOs [Community Based Organizations] is going to give us the best results,” she said. “We’re going to make sure that the grassroots movement and the other people in our communities that want to be able to be supportive and show solidarity can do that.”

Representatives from two volunteer-led organizations at Friday’s meeting said that volunteers haven’t gotten any financial support from the city. In a presentation, a representative from the mutual-aid Police Station Response Team estimated volunteers have spent about $2.4 million on food and water for migrants and nearly $1 million on supplies. They’ve also supplied about $2.9 million in free labor, according to the estimate.

“The way the mayor’s office is using the term ‘mutual aid’ seems like marketing,” Mari, a volunteer with the Edgewater Mutual Aid Network, told the Weekly. “Mutual aid is working in solidarity with people. It’s knowing that people are the experts in their own lives . . . Mutual aid is not in alignment with helping take on city jobs. The whole relationship between the city and volunteers is exploitative, and the people who suffer the most are the asylum seekers.”

Erika Villegas, lead volunteer at the 8th (Chicago Lawn) District police station, told the Weekly she is “personally concerned” about how long asylum seekers will be in the tent camps because families have been staying at police districts for months. “We need to know what the plan is before people are stuck for six-plus months in tents,” she said.

At Friday’s meeting, officials directly addressed concerns about the camps. Pacione-Zayas said the tents have “solid, insulated, prefabricated walls” and HVAC systems with backup generators that can maintain temperatures of at least 70 degrees in cold weather.

“I’ve heard that people are concerned that this is a militarized camp, that it will be run with armed guards,” Ponce de León said at the meeting. “That is not how this will be operated.” The camps will be subject to the same policies the Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS) has for brick-and-mortar shelters, and asylum seekers will be “free to come and go,” she said.

Ponce de León emphasized that the camps are just one solution and that the city is still “doubling down on opening up brick and mortar spaces,” including continuing to look at city-owned properties since those are the most cost-effective option, and that they will aim to use some of the new shelter capacity to serve the “broader community of unhoused Chicagoans.”

Another concern is who will staff the camps. When Johnson announced the tent camp plan on September 7, it was not immediately clear who would be building or staffing the camps. Favorite Healthcare Staffing, which the previous administration hired to staff brick-and-mortar shelters, brought in out-of-state contractors.

“As much money as we are spending, how much are we really recycling in our community?” Ald. Jeanette Taylor (20th Ward) asked.

Ald. Pat Dowell (3rd Ward) echoed Taylor’s concern, stating frankly, “This is a business and we want to be part of this new business.” She asked what specific services that Garda will be sub-contracting to local entities.

Pacione-Zayas said GardaWorld will provide sleeping and eating quarters and laundry facilities, and will subcontract local providers for wraparound services after the first thirty days of camp setup. The exact locations for the camps have not yet been determined, she said, acknowledging that the city is behind on this process.

Pacione-Zayas told the Weekly that the administration is encouraging GardaWorld to hire staff for the tent camps locally. To further support the local economy, Ponce de León announced during Friday’s meeting the release of two new RFPs that will replace existing contracts and prioritize hiring local businesses, one for food service providers to shelters and the second for community-based shelter operators.

Racial disparity in resource allocation is another reason why some are against the camps. Some public speakers disagreed with the large investments in migrant housing, such as Zoe Lee. “This is the main concern: finding all this money to house [the migrants],” Lee told alderpersons at Friday’s meeting. “The fact that you guys take it and screw the Blacks and go directly to ‘we have to help the migrants’ when we still need it.”

Throughout the meeting, public commentators and presenters advocating for more city support for migrant programs were interrupted with boos, especially when investments were brought up, causing Vasquez to ask for order multiple times.

Last year, Illinois received $53.5 million from the federal American Rescue Plan Act to run the Illinois Housing Development Authority’s Asylum Seeker Emergency Assistance Program in which eligible migrants can receive up to six months of rental assistance. The Chicago Department of Housing made an additional $4 million available for emergency rental assistance funds for migrants.

In August, the Illinois Answers Project reported that the city had spent just fifteen percent of the $52 million budgeted for local homeless programs.

“You’re going to start a race war,” warned Taylor, “Because you’re choosing who you care for.”

On Thursday, the mayor’s deputy chief of staff, Cristana Pacione-Zayas, affirmed that the city is moving forward with the GardaWorld contract. The administration will include feedback from “stakeholder groups such as mutual aid volunteers and community-based organizations,” Pacione-Zayas told the Weekly. “That’s going to be an exercise that we’re going to undertake over the next few weeks.” There will also be a system for filing grievances, she said.

Gov. Pritzker was asked Thursday at a press conference about the tent camps. “I have concerns about it, and we continue to have conversations about it,” Pritzker said. “With a lack of existing buildings to put people in, I know the city has looked at this as one of its options. But I don’t think this is the only option.”

The comments drew sharp criticism from mayoral allies and organizers alike who said the state hasn’t done enough to support Chicago or opened any shelters in the city since Johnson took office.

“I think there’s all kinds of options,” Pacione-Zayas said. “It’s just a matter of availability; it’s a matter of resources. It’s a matter of, also, will. There’s so many different routes you can go. I think for us, what’s most important is expediency with getting folks off of police station floors and airport floors.”

Pritzker said on Thursday that the state has spent $328 million to help Chicago manage the influx of asylum seekers. On Friday, his office announced another $30 million grant to the city for migrant support. The sole shelter the state is helping open in Chicago, in a shuttered CVS in Little Village, has taken months to set up, despite being approved in May—a point Ald. Carlos Ramirez-Rosa (35th Ward) brought up on Twitter Thursday and drove home in an impassioned speech at Friday’s committee meeting.

On Monday, Jordan Abudayyeh, the governor’s deputy chief of staff for communications, said in an email the governor’s office is “working in close collaboration with the mayor’s office” to get the Little Village CVS opened. “ We have multiple meetings a week with the mayor’s team and have a productive relationship with his team working on this crisis,” Abudayyeh said.

At Friday’s meeting, Ponce de León said the city is asking the state to identify shelter locations elsewhere in Illinois with “culturally congruent communities” that can provide wraparound support. The state hasn’t yet agreed to do so, but in August, it made $42.5 million available to other municipalities to apply for funding to support the migrant response. Ponce de León said that the state has received applications from several municipalities.

Ald. Rossana Rodríguez-Sánchez (33rd Ward) told the Weekly on Saturday that the City Council Latino Caucus met with the governor’s office two weeks ago, but no one from that office mentioned opening shelters in Chicago. “I can’t tell you why,” she said. “We should be working collaboratively and make sure we have open channels of communication to deal with this.”

She added that the state was “very proactive” when the first buses started coming in. “There was a lot of work we were able to do [with] the state” last year, she said. Now, “The most important thing is to make sure people are sheltered, and the state hasn’t been materially helping with that.”

Pacione-Zayas told the Weekly that the timeline for getting people into shelters and permanent housing is “a moving target,” particularly if the pace of bus arrivals continues to rise. “We just have to constantly monitor it and deploy,” she said. “Do we double down on places where we have our longest-staying folks and deploy our additional resources there, so we can move them quicker? Do we double down on the folks that have more complex configurations, like the ones that have a lot more people [and] therefore can have conditions that are obviously not ideal, and more challenges? It just kind of depends.”

The Illinois Coalition of Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR), which has advocated for immigrants since 1986, has been providing case management for asylum seekers in Chicago for the past year. In a statement provided to the Weekly, Veronica Castro, ICIRR’s deputy director, said involvement at all levels is key.

“From our experience, we know that federal, state, and local governments all play a critical role and have a responsibility in addressing the ongoing, humanitarian crisis that asylum seekers, community organizations, and mutual aid groups continue to face day to day,” Castro said. “We remain committed to ensuring that new arrivals are welcomed with dignity and respect, as well as organizing to win long-term solutions that can be accessed by any Chicagoan in need of support.”

Shortly after 4pm Friday, about fifty people gathered in Daley Plaza to protest the tent camp plan. Speakers linked the issue of housing asylum seekers to that of unhoused Chicagoans as well as the economic sanctions the U.S. government has imposed on Venezuela since 2018.

“This is not only a financial crisis, it also has to do with the unhoused people in Chicago,” said the first speaker, who was not identified by name. “It’s the same struggle.”

David Orlikoff, a member of the 14th (Shakespeare) Police District Council who has been assisting volunteer mutual-aid efforts there, said that as long as the sanctions aren’t lifted, Venezuelans will continue to seek asylum here. “I haven’t heard enough discussion in our Democratic city about how our federal Democratic Party is causing these very harms that we’re experiencing,” Orlikoff said. “Yes, we need their support in finding more housing and resources, but we also need Joe Biden to end the US sanctions against Venezuela.”

He added that it’s “racist” that the federal government has resettled Ukrainian refugees but not Venezuelan asylum seekers, “when federal foreign policy is directly causing both crises.”

A mutual-aid volunteer who attended the protest but declined to give her name told the Weekly that the city should seek input from asylum seekers about possible solutions. “When people are not included in the decisions that [impact] their everyday lives, everything turns out disastrously,” she said.

On Sunday, some asylum seekers at the 14th (Shakespeare) District expressed skepticism about the tent camp plan. “None of us want to go to the carpa [large tent],” one woman said.

The Johnson administration and its allies have pushed for help from the state and federal governments for months. In August, Congresspersons Jonathan Jackson (IL-1) and Ramirez (IL-4) joined alders to quietly tour the 3rd (Grand Crossing) Police District and a shelter at former Wadsworth Elementary School in Woodlawn ahead of what sources described as a behind-the-scenes push for more federal assistance. To date, the feds have provided about $41 million to Chicago for migrant aid.

Pacione-Zayas said that the total Chicago has spent on managing the migrant influx since August 2022 could be between $319 and $362 million.

In September, Johnson and Ponce de León met with federal officials in Washington, D.C. to “better coordinate” their efforts. After the visit, Biden announced he would extend temporary legal status to Venezuelan refugees who arrived before July 31, 2023, which will allow some 470,000 asylum seekers to find work. It’s unclear what will be made available to those who have arrived since then.

The threat of a federal government shutdown, which would have impacted officials’ ability to process migrants’ work permits, was averted late Friday night when Congress passed a stopgap spending bill that will keep the government open through at least mid-November. But with a minority of far-right Republicans wielding outsize power in the House, the threat of gridlock—and its repercussions for migrant aid—remains.

Congresswoman Delia Ramirez (D-4) said that as asylum seekers are able to get work permits, the need for emergency shelter should decline. She added that the federal spending stopgap gives Democrats an opportunity to negotiate for funding in the appropriations bill for cities like Chicago to provide emergency shelter support.

“I also think this is going to require, even more so, executive leadership” from President Biden, Ramirez said. Biden “now has the opportunity” to expand work permits by executive action outside of the appropriations process to make them available to asylum seekers who have arrived since July 31.

Gutierrez, of OCAD, said the federal government should be allocating more resources to get asylum seekers permanent housing. “The overall expectation [is] that states are going to have to do it on their own, or cities are going to have to do it on their own, and I think that’s completely irresponsible of the federal government,” they said.

At Friday’s meeting, Ponce de León laid out some concrete requests that the city will make of the federal government, including more flexible funding streams. Currently, “the federal government requires us to utilize these funds for only covering the costs of somebody staying in a shelter for forty-five days,” she said.

The city will also request a federal mass waiver for applications for work authorization requests made possible under the new temporary protected status, which can cost upwards of $500 each. “When you are able to work, you are able to then lessen your dependency on public dollars and at this point, we need people to have the legal ability to work,” Ponce de León said.

Joyner, a Venezuelan asylum seeker who has been staying at the 14th District police station since August 12, said he only wants the chance to work.

“In truth, we hope . . . that they help us with this issue of having papers as soon as possible, to be able to apply for a job, a permanent job, and to be able to cope with one’s own things,” Joyner said. “To pay with [our own] income to not be a burden on the state either, but on oneself—that is, to fulfill the goals for which I came [here], to move forward and be a better person.”

Wendy Wei is South Side Weekly’s immigration editor and covers interracial solidarity between communities of color. Jim Daley is an investigative journalist and senior editor at the Weekly.