The largest and greatest sludge plant in the world… wasn’t intended to be that way,” Richard Lanyon, former executive director of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago (MWRD), said to a rapt audience, a playful smile spreading across his face. “It just happened.”

It’s true: Cook County’s very own Stickney Water Reclamation Plant is just about the largest in the world, processing sewage and stormwater from a 260-square-mile area that includes the South and West Sides, some of the North Side, and forty-six suburbs. Just outside the city limits on Pershing and Central, the plant remains out of sight and out of mind for most Chicagoans. But it’s central to the history Lanyon tells in his most recent book, West by Southwest to Stickney: Draining the Central Area of Chicago and Exorcising Clout, which he visited the Chicago Maritime Museum to speak about in late April.

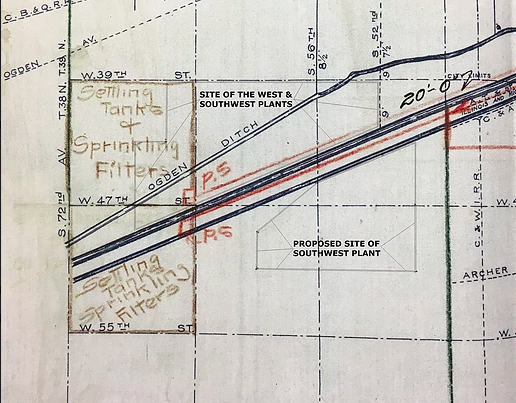

The opaque book title is a play not on the Hitchcock movie, but on the names of the Stickney plant’s earlier incarnations. First called the West Side Sewage Treatment Plant when it opened in 1930, as the plant processed sewage from greater portions of the South Side, it added a Southwest branch, and then the two merged to become the West-Southwest Sewage Treatment Works. In 1988, as part of a larger wave of rechristenings, the MWRD stopped naming the site for its breadth of coverage and instead renamed it for the small village to its west, Stickney. West by Southwest to Stickney, the third in Lanyon’s four-book series on the development of Chicago’s sewage system, offers an insider’s account of how those plants, and the District’s sewer system, have been integral to flood prevention and public health efforts on the South and West Sides.

Chicago’s sewer system actually dates back much further than its first sewage treatment plant. Up until the 1850s, the city’s earliest sewage pipes sent downtown sewage directly into Lake Michigan, with gravity’s aid. In light of the unpleasant odors and rising typhoid rates that followed, the city decided shortly thereafter that it was in its best interest to send its sewage not toward but away from its sole source of drinking water.

In the mid-1850s, the city started diverting most of its sewage into the Chicago River and the Illinois and Michigan Canal. But though both channels provided a route for ships to move to the southwest and into the Mississippi River System, despite engineers’ best efforts (including temporarily reversing the river in 1871), the water (and waste) carried by both still flowed naturally into the lake. In 1885, when a storm sent the canal’s most polluted waters far out into the lake, near the drinking water intakes, the city panicked, and four years later created the Sanitary District of Chicago (as the MRWD was known until 1988). The agency was tasked with permanently reversing the canal and the Chicago River, to prevent future contamination of the lake. By 1900, the new district had built the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal—an improvement on the Illinois and Michigan Canal—and succeeded in reversing the Chicago River, once and for all diverting its polluted waters southwest, into the Des Plaines River and then the Mississippi.

But as Lanyon writes in the first chapter of West by Southwest, “Reversing the flow of the Chicago River and South Branch wasn’t enough to keep sewage out of the lake.” To get to that point, Lanyon argues, it took decades of building out intercepting sewers, pumping stations, and waste treatment plants, from the early 1900s through the thirties and forties. What follows is a fascinating but labyrinthine account of the development of Chicago’s current waste management system.

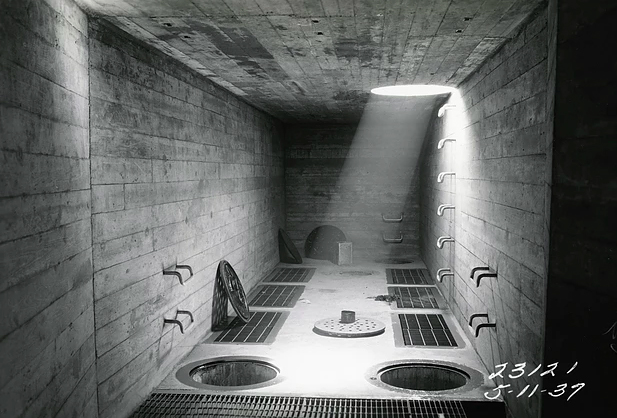

It’s easy to understand why the work of the District following the Chicago River reversal goes underappreciated: Plagued by corruption and controversy for most of the twentieth century, the District operated in an ad-hoc fashion, adding pumping stations and intercepting sewer systems when it became apparent that they couldn’t do without them. The West Side Sewage Treatment Center, for instance, became operational in 1930. The District operated a small railroad to transfer its processed sewage sludge from the facility to a 950-acre dumping site to the southwest. But by 1934, “The depth of material was encroaching on the tracks on top of the trestle,” Lanyon writes, and expansion was needed; the District opened a second processing facility on the same site in 1939. The District’s stop-and-start building over this period—especially of new sewage treatment facilities and intercepting sewer lines on the South and West Sides—did not exactly invite the awe of the public in the way that the river reversal did.

But the infrastructure that the District was building through the thirties and forties and forties, at however variable a pace, was for the first time infrastructure that wouldn’t direct sewage into the Chicago River system. Instead of pumping into the river—and to less fortunate cities downstream—the District started using technology to process sewage into “sludge,” a composted, air-dried biosolid rich in nutrients. Over the years, the agency has marketed sludge to farmers, gardeners, landscapers, and, recently, to those working to rehabilitate brownfields and other contaminated sites. (Despite the move away from polluting the river on purpose, in heavy rainfall, the sewer system still backs up into the Chicago River; the website istheresewageinthechicagoriver.com helpfully tracks when this happens.)

There is likely no person in the city of Chicago better equipped to tell this story than Lanyon, who spent fifty years working in Chicago water management before retiring in 2010. At the Maritime Museum, he recalled parts of his childhood in a house in Englewood that, like most other homes on the low-lying South Side at the time, often flooded to varying degrees of severity. And as an adult, he was present for the construction of the infrastructure that most helped to alleviate flooding on the South Side: the 1964 Racine Avenue Pumping Station on Pershing. Replacing an older pumping station with less capacity, it pumped sewage from a 36-square-mile area, from Western east to the lakefront, and from 87th up to Taylor.

It’s a shame that the book reads like a city agency report, largely lacking in visuals, compelling narrative structure, or critical reflection. (Lanyon is involved in digitizing the MWRD’s archival photos, however, and has made a number of photos available online through the publisher’s website.) Each chapter is so dense with dates and details—about permits, contracts, and whom they were awarded to—that it’s difficult to develop an overarching picture, let alone a coherent timeline. The development of Stickney is first detailed in the sixth chapter, some 250 pages in, despite the fact that, aside from the river reversal, it is the most significant piece of infrastructure in the MWRD’s history. Meanwhile, the author’s attention to corruption in the MRWD, promised in the book’s subtitle (“Draining Central Chicago and Exorcising Clout”), comes in a small chapter at the end, where he treats the agency’s ghost payrolling, corrupt contracting, and other crooked practices as concerns of the past. (Recent investigations by the Tribune and Better Government Association suggest otherwise.)

It’s not that Lanyon doesn’t see the forest for the trees (or, er, the sewer system for the lines). At the Maritime Museum, Lanyon spoke compellingly about how land use in the early 20th century affected the growth of the city’s sewer system. Midway through his talk, he put up on the projector an early sewer map covering Fullerton through 87th Street. It ended at 87th, he explained, because for a long time that’s where the city ended—but it stopped at Fullerton because the Chicago-Milwaukee-St. Paul railroad, which like most other railroads until the 1920s ran at street level, had stopped the District from developing any further. “This [rail line] became a natural boundary for sewers because when they were laying out sewers they didn’t want to cross railroad tracks, and railroads didn’t want pipe go underneath the tracks anyways,” Lanyon said. “So a lot of the present-day sewer maps are defined by railroads.”

Though such insights, and many other historical insights in the book, are intriguing, the fact remains that in the book, the agency’s complex role in environmental degradation and public health doesn’t get the critical discussion it requires. So the MWRD directed sewage into Chicago’s waterways for several decades—which municipalities didn’t in the late 19th and early 20th centuries?—but the sewage processing plants that helped them to redirect the sludge elsewhere are themselves polluting the waterways with phosphorus, according to a 2017 press release from the Natural Resources Defense Council, “Fueling algae blooms and lowering water quality in the Chicago River System.” And, in the 1970s, the sewage sludge that the MWRD distributed to farmers and gardeners contained exceedingly high quantities of the heavy metal cadmium, an industrial waste product that can cause severe kidney damage. Acknowledging these events would have made for a more compelling history of the agency and its infrastructure.

Nonetheless, Lanyon has undertaken an impressive feat in pulling together this history—not to mention the two histories preceding it—and the book will serve as a guide for researchers and all those who have an interest in the nitty-gritty of Chicago’s underground infrastructure.

Pleasure readers may want to pass on this book in favor of, or at least read it in tandem with, other, easier reads about the region’s watershed and sewer infrastructure. But if you choose to soldier through, you’ll find some solace in learning (in the second-to-last chapter of the book) that even Lanyon, the agency’s former executive director, sees the management of the sewer and stormwater systems as “the most perplexing infrastructure problem” in all the city.

Emeline Posner is the Weekly’s food & land editor and a freelance writer. She last wrote for the Weekly earlier this month about the history and future of community gardens connected to First Presbyterian Church.

Emeline, this is a great review. Thanks! The detail is there for those who really want to know.

Emeline, thank you for this very interesting article. I included a link to your article in an piece entitled “Chicago Sewage Increasing Coronavirus Risk” over on Medium.