In early December, the Teamwork Englewood office received an anonymous call from an affiliate of the Chicago Department of Public Health alerting them that the Englewood STI Specialty Clinic—one of four city-run clinics offering free testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections—would be shutting down.

On December 11, Nicole Johnson sent out an email to the neighborhood’s Health & Wellness Task Force, of which she is a member, outlining her concerns: that Englewood residents without health insurance would be left without reproductive healthcare; that walk-in treatment and testing for HIV and other STIs would cease to be available in the neighborhood; and that this marks a continuing trend of public disinvestment from Englewood.

“The city has this incessant reliance on private services to address public needs,” she wrote.

The city clinic, housed in the basement of 641 West 63rd Street in the same building as a University of Illinois-Chicago Mile Square Health Center and a Howard Brown Health Clinic, ceased operations on January 12.

According to a CDPH spokesperson, federal funding cuts prompted the clinic’s closure. These cuts, paradoxically, resulted from Chicago’s recent success in HIV prevention and treatment.

“This past year, the number of new HIV infections hit an all-time low for Chicago and we remain committed to completely eliminating HIV infections within the next ten years. […] Because of the progress we have made in achieving historic lows in new HIV infections, Chicago will receive less federal grant money in 2018,” the CDPH said in a statement.

It’s true that new HIV diagnoses are at a record low in Chicago—just last month, Rahm Emanuel’s office announced that diagnoses are down fifty-five percent from 2001, and that eighty percent of those newly diagnosed are linked to medical care within a month. As the city released this data, Emanuel also announced Chicago’s participation in the international Fast-Track Cities initiative, becoming the fifteenth city in the United States working to hit the United Nations’ HIV eradication targets by 2020.

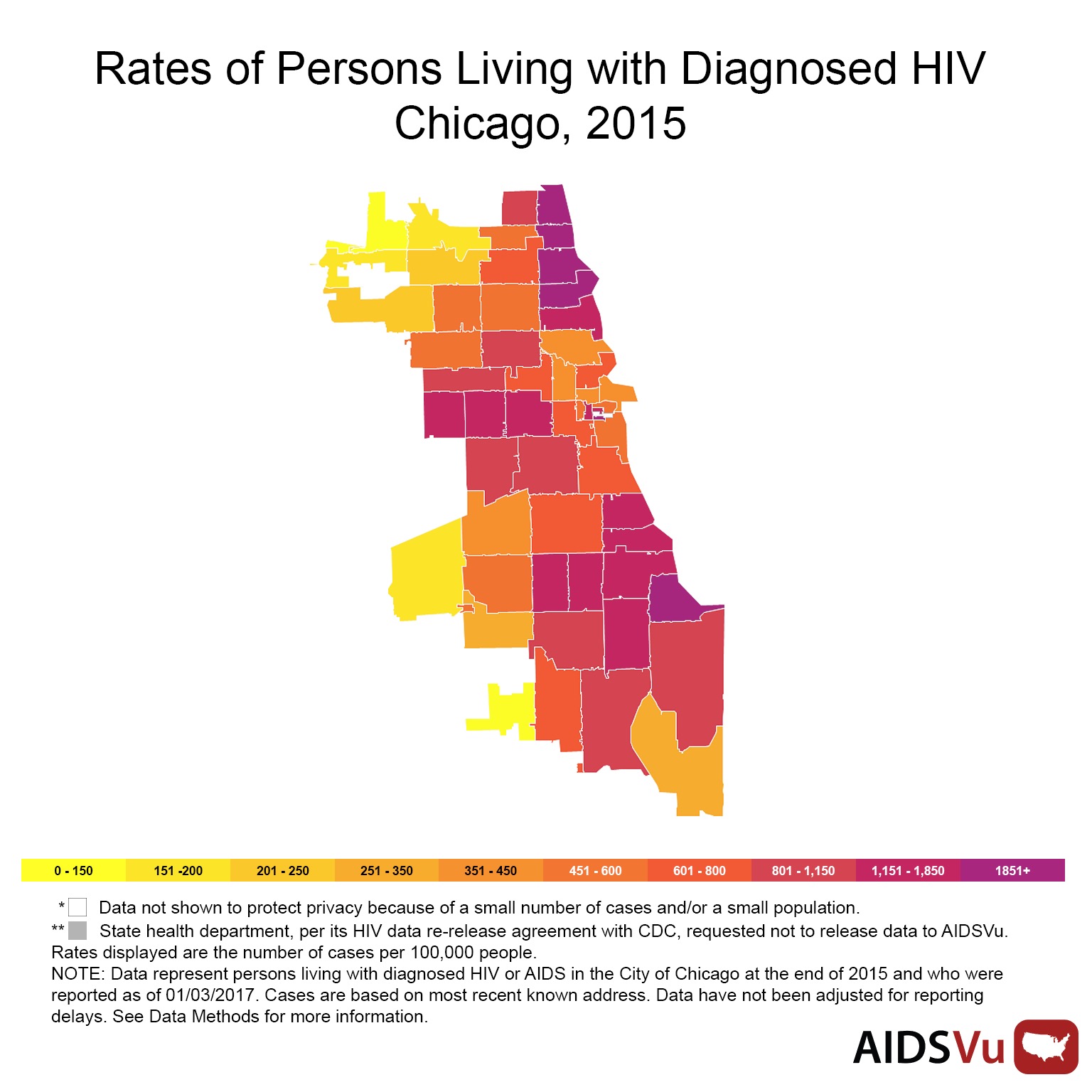

However, these encouraging numbers are not distributed evenly throughout Chicago, which the city’s 2017 HIV/STI Surveillance Report notes. “There are health disparities when it comes to STI infections. Specifically, infections are concentrated in high hardship, low childhood opportunity community areas and among specific populations,” CDPH Commissioner Julie Morita wrote in the report’s introduction. “Black women accounted for nearly 27 percent of all chlamydia cases in 2016, and Black men nearly 22 percent of all gonorrhea cases in 2016, while they only account for 17 and 14 percent of Chicago’s adult population respectively.”

The mayor’s press release around the report acknowledges and addresses this disparity specifically regarding HIV: “While Chicago has seen declines across all ethnic groups over the past several years, African American men between 20-29 years of age continue to face disproportionately high rates of infection. As such, CDPH and its partners will continue to focus resources specifically toward closing this disparity.”

Englewood would be an ideal locale for the mayor to bring his commitment to young Black men into practice.

“We have high numbers of HIV incidence,” said Michelle Rashad, a chair of the Englewood Health & Wellness Task Force. She cites numbers from the Chicago Health Atlas: Englewood’s rate of HIV incidence (that is, the number of new cases identified in a year) is 50.7 per 100,000 in comparison to the Chicago average of 34.2 per 100,000.

“So we know HIV is an issue. The fact that funding is being cut from it is shocking. It’s shocking especially because there’s always a need, but someone makes the decision that that need isn’t a priority and cuts the funding. That’s just very disheartening,” said Rashad.

“This follows a larger trend of CDPH putting off direct provision of care into the hands of not-for-profit providers,” said MJ Johnson, a community health worker from Englewood and Community Engagement Specialist at the University of Chicago’s Center for Interdisciplinary Inquiry & Innovation in Sexual & Reproductive Health (Ci3). “This is the continuation of that trend, even given the funding concerns and the oddity of the timing. It is part of a pattern that’s been established.”

Listen to former Weekly editor-in-chief Bea Malsky discuss this story on the January 23 episode of SSW Radio, the Weekly’s radio hour on WHPK:

HIV—human immunodeficiency virus—has always been a disease of the marginalized in this country, a slow-building illness stigmatized and rendered invisible by interlocking prejudices surrounding queerness, poverty, and Blackness. Left untreated, HIV develops into AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. AIDS prompts a failure of the human immune system, and, until recently, was a death sentence.

With recent advancements in antiretroviral therapy and preventative care, AIDS is now a condition many people live with. The Center for Disease Control estimates that there are roughly 1.2 million people in the United States living with HIV. However, testing is critical: it must be treated early in order to be managed, and the CDC estimates that one-eighth of those 1.2 million are not aware that they are infected.

To have HIV/AIDS is to become individually vulnerable to opportunistic infections, and to live in a community without adequate healthcare resources is to become collectively vulnerable. Two driving forces behind the dropping HIV rates in Chicago are both under threat by the current federal administration: the availability of a preventative pill called PrEP, which must be taken daily to maintain its effectiveness, and the Affordable Care Act.

Since being signed into law in 2010, the ACA has allowed an estimated 12,000 Illinois residents living with HIV to access regular and affordable care. Without insurance, typical medical costs for yearly treatment range from $20,000 to $30,000. “Life happens, and people say, do I pay the rent, or do I pick up my medications? People start making choices,” David Ernesto Munar, president and CEO of Howard Brown, told the Chicago Tribune late last year. The Chicago Health Atlas estimates that twenty-two percent of Englewood residents are uninsured.

There are two clinics remaining in the building on 63rd Street: Howard Brown and UIC Mile Square. The city says that these two will pick up the slack left by the closure of the city clinic, and Maya Green, site medical director of Howard Brown’s 63rd Street location, reports that they started providing walk-in services this month.

“Approximately twenty to twenty-five walk-in patients a day were estimated by the city and we expect that we will absorb those in collaboration with our other partners in the building,” she said. “We anticipate being able to serve Englewood’s sexual health needs through our walk-in clinic, as we have an excellent history in Chicago of providing these services at our other North Side locations.” Both remaining clinics provide treatment on a sliding payment scale for uninsured visitors.

With the threat of dwindling public resources, the Englewood Health & Wellness Task Force is working on next steps, including a Health Navigators program that would help residents locate and use existing resources in the neighborhood. They continue to advocate for ample, affordable, and accessible care.

“How are we actually improving people’s livelihoods so that they can be healthy and have consistent access to healthcare outside of a crisis?” Johnson asked. “I’m thinking about communities like Englewood or Austin or Roseland, which are sitting at intersections that are hyper-vulnerable to infectious diseases. More than just increasing funding for HIV care, we need social services in the area, and a commitment from public institutions. And that’s not happening.”

Update (1/26/2018): After the publication of this article, the CDPH provided the following information: The Howard Brown and UIC Mile Square clinics are planning to increase their capacity in order to see 200 patients a day, though neither clinic is receiving new funding from the CDPH for their increased walk-in services.

Bea Malsky works at Ci3, a public health research and policy lab with a focus on adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

6 alderman and nobody saw this coming….

Thank you so much for reporting on this! Very well written and so true!

Thank you so much for the update on this issue,

I will be writing grant proposal on HIV prevention in Southside of Chicago for class project.