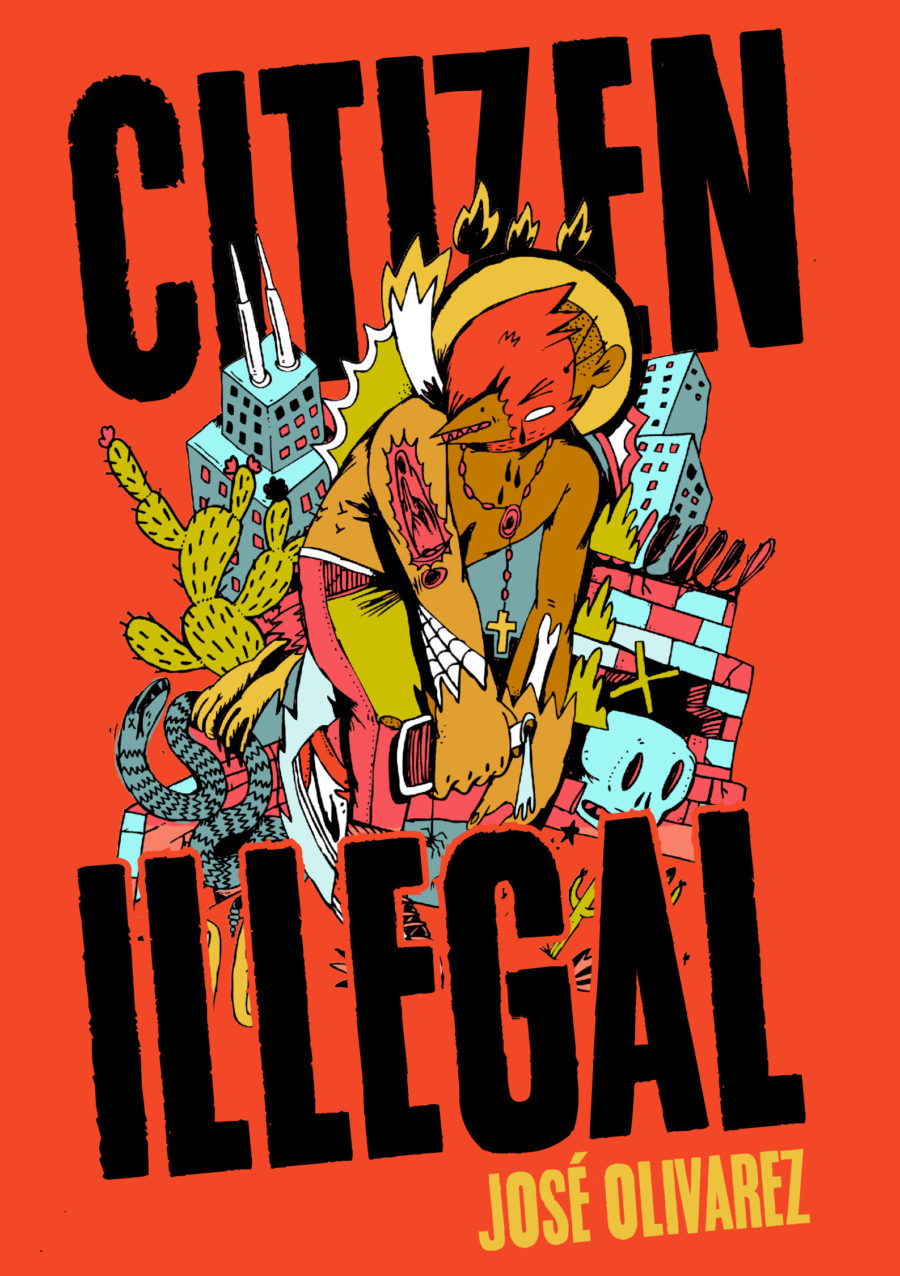

Citizen Illegal is the debut poetry collection of José Olivarez, a Chicago-based poet, educator, and performer. Published in 2018, his collection explores race, immigration, and community in a way that few writers have. As the son of Mexican immigrants, much of Citizen Illegal explores the complexity of first-generation identity and community in between the nuances of citizenship and belonging.

When Citizen Illegal came out four years ago during the Trump administration, it felt especially timely. In the midst of draconian border policies and immigration raids, Citizen Illegal cannot be disentangled from the politics of then or now.

The collection’s title and its first poem “(Citizen) (Illegal)” put legality, assimilation, and this contradictory set of identities at the forefront. The parentheticals interrupt the stanza’s flow, levying state and societally-imposed judgment on everyday experiences.

“if the boy (citizen) (illegal) grows up (illegal) and can

only write (illegal) this story in English (citizen), does that make him more

American (citizen) or Mexican (illegal)?

— “(Citizen) (Illegal)”

“My Parents Fold Like Luggage” tells the story of his parents’ migration from Mexico. “My Family Never Finished Migrating We Just Stopped” centers on migration narratives in resistance to border security forces. Meanwhile, “Mexican American Disambiguation” unpacks the sense of identity that comes from not being Mexican, not being American, but something else:

“my parents are Mexican who are not

to be confused with Mexican Americans

or Chicanos. i am a Chicano from Chicago

which means i am a Mexican American

with a fancy college degree & a few tattoos.”

— “Mexican American Disambiguation”

“…my Mom

was white in Mexico & my dad was mestizo

& after they crossed the border they became diverse.

& minorities. & ethnic. & exotic

but my parents call themselves mexicanos,

who, again, should not be confused for mexicanos

living in Mexico…”

— “Mexican American Disambiguation”

“Mexican American Obituary” finds Olivarez criticizing Latinx communities and their willingness to look away from the oppression of Black people while attempting to become American or assimilate.

“Juan, Lupe, Lorena all died yesterday today

& will die again tomorrow

asking Black people to die more quietly

asking white people not to turn the gun on us.”

— “Mexican American Obituary”

One of my personal favorites, “Interview,” is a series of different responses to the question, “Where is your home?” that capture this feeling of being out of place in Mexico, New York City, and Chicago. Several poems explore the guilt that comes with being first- or second-generation, which feels only too familiar to me as the child of immigrants myself. This emotion comes from straddling two cultures at once and the pressure it brings—remembering your family’s sacrifices, the life they left behind, and the life they live now.

But Citizen Illegal does not spend its entirety mourning these questions of home and identity. Rather, it celebrates the mundane markers of home. Growing up in Calumet City, Olivarez is a Chicago poet more than anything. There’s a sense of nostalgia that demands to be seen. He is reverent towards cheese fries, vaporú, and bitter Chicago winters, and these odes to little things are constantly popping up throughout the collection.

Stylistically, Olivarez is fond of lowercase typeset poems and ampersands, and he carries the collection forward with a conversational tone. I started some poems chuckling and finished them a bit sad inside. The front flap of the collection’s cover describes him as “using everyday language that invites the reader in,” and that may be the perfect way to describe it.

Inspired by rap and hip-hop and coming from a spoken word performance background, he plays with language in new and inventive ways. Olivarez’s writing feels sincere, almost unbearably so, like a late-night conversation with a new friend. His poems call back to one another, reprising the themes of love, family, and community that have already been established.

There’s a dry wit and humor that Olivarez constantly brings to his writing. His imagination lets him be inventive with language and atmosphere. Placed throughout the collection is a running thread of eight “Mexican Heaven” poems—all anachronistically showing heaven and its familiar inhabitants. Each poem calls back to one another as you pace yourself through the collection. At public readings, he reads them all together, but in the collection, they are broken into parts and set the tone for each new section.

They layer new characters and images, depicting Jesus as your reincarnated cousin from the block, St. Peter as Pedro welcoming all the Mexicans at the gate, and God as “one of those religious Mexicans” who the others must drink and smoke discreetly around. Sometimes, heaven is dirty because the women refuse to clean. Sometimes, Mexicans sneak into heaven or are forced to work in the kitchen until they reach their own version of the American dream. But, of course:

“there are white people in heaven, too.

they build condos across the street

& ask the Mexicans to speak English.

i’m just kidding.

there are no white people in heaven.”

— “Mexican Heaven”

In many ways, envisioning the fantastical informs how he tells stories. In an interview with the American Writers Museum, Olivares described seeking inspiration from Black mentors, learning about Afrofuturism, and thinking about the potential for Latinx stories. “Let me try and imagine what a future might look like for us that doesn’t end in death, assimilation, or deportation,” he said.

In “Gentefication,” whose root word gente means “people,” Olivarez writes the opposite of gentrification to life. In an imagined world where Gwendolyn Brooks comes back to earth to smell tamales and poetry workshops are being taught in the shade, a neighborhood rejoices. Instead of seeing a community displaced, people return home to celebrate and collect like grains of sand.

“the whole block is alive

& not for sale. the treaty of guadalupe hidalgo

rescinded.

it’s happening on our block & maybe it’s happening on your block.

the bad news is the president sends the national reserve. The good news is

they’ll never find us. we pack everything

into the trunk of a Toyota Corolla, when la migra

comes,

their dogs bark & spit, but all they find is grains of sand.

— “Gentefication”

Citizen Illegal offers a relentless reminder that home is not a country, but the markers of the communities that keep us alive. Drawing from the likes of Brooks and Sandra Cisneros, Olivarez manages to create vivid depictions of the lives and communities around him and gives them full agency in spite of their sociopolitical conditions.

José Olivarez, Citizen Illegal. $16 (paperback). Haymarket Books, 2018. 87 pages.

Reema Saleh is a journalist and graduate student at University of Chicago studying public policy. She can be followed on Twitter or Instagram at @reemasabrina. She last interviewed artist Akilah Townsend for the Weekly.