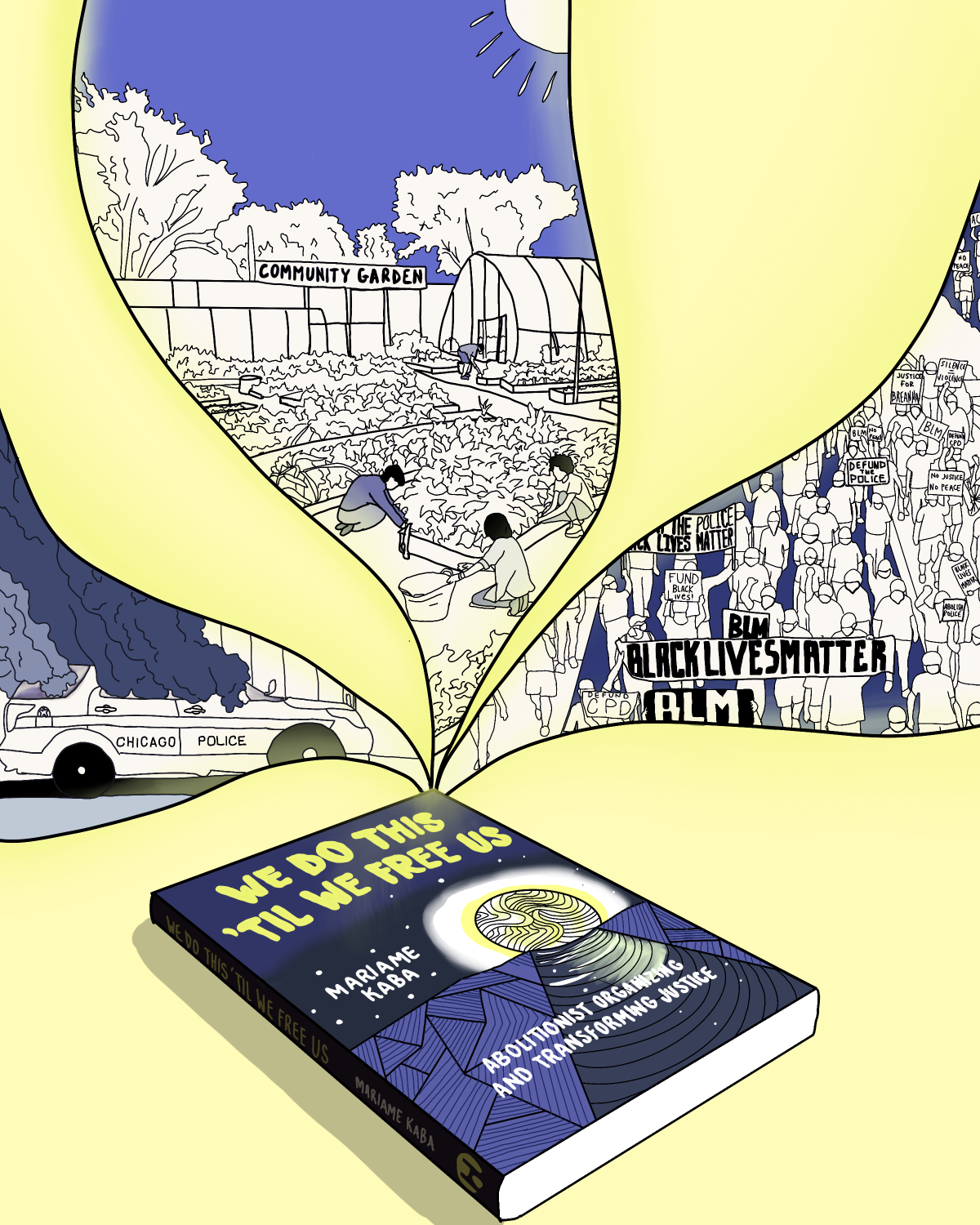

We Do This ‘Til We Free Us is a collection of essays and interviews that explore the abolition of police and the prison industrial complex (PIC) and the power of transformative justice, written by and conducted with organizer, educator, and abolitionist Mariame Kaba.

Published in February 2021, editor Tamara K. Nopper notes in the introduction that Kaba had “declined previous requests from Haymarket Books to publish a collection of her writings,” but that “as calls for defunding the police accelerated” in the wake of the 2020 uprisings, “so did broader conversations about abolition.” In an effort to get “as many people as possible to learn more about abolition,” Kaba agreed to compile and publish the anthology.

We Do This could be said to have many authors. Several of the essays are co-written with other people, interviewers interject with their thoughts while asking Kaba to elaborate on her own, and even Kaba herself often invokes the words of fellow writers, comrades, friends, mentees, and family.

It seemed fitting, therefore, that when several writers expressed interest in reviewing We Do This for South Side Weekly, we accept more than one perspective. In the end, we landed on four writers, each with different experiences and backgrounds, sharing what it was like to read and react to this book.

Coming from an organizing background, Alycia Kamil sought out We Do This thinking it might add some vocabulary to concepts she was familiar with, but found herself struck by the possibility of a single question posed by Kaba—“Let’s begin our abolitionist journey not with the question, ‘What do we have now, and how can we make it better?’ Instead, let’s ask ‘What can we imagine for ourselves and the world?’” Kamil explores the power of that question as it relates to moving away from reliance on the prison industrial complex and the practice of hope as a discipline.

In their essay, Rubi Valentin explores the meaning behind Kaba’s declaration that “abolition is not about your fucking feelings.” They write: “emotions shouldn’t cloud political commitments to the basic principles of abolition, but Kaba demonstrates that it’s more difficult to do so than it seems, even for abolitionists.” In Valentin’s case, it’s the murder of an uncle that tests this commitment and sparks conversations in their family about police and accountability.

Having experienced criminalization and being currently involved in a mutual aid organizing project, Melissa Castro Almandina found We Do This helpful in providing language and frameworks for ideas they’ve identified with all of their life. Melissa writes about how Kaba’s demonstration that everybody, at one point or another, will harm others, can be freeing when we build spaces to come together as communities, hold ourselves accountable, and heal.

Finally, Chima Ikoro, the Weekly’s community builder and organizer of this Lit Issue, uses this space to reflect on their upbringing and how it can be difficult for “Black and Brown people in marginalized communities” to go so far as to want to defund police “despite never being helped by them.” They go on to explore the ways in which We Do This is full of accessible, compelling writing on abolition, and how important that can be to bringing people into the movement.

What follows is less a collective review than a collection of personal reflections on We Do This and how the book has shaped these writers’ and organizers’ lives and thinking about justice, care, and the possibilities of tomorrow.

I picked up this book in low spirits from the hardships that transpired in the summer of 2020. After an exhausting past three months of seeing so many of my friends, myself included, being harmed by the systems we were fighting against, stepping away from the frontlines was painfully needed. I turned to what initially brought me into these spaces—literature. I was familiar with abolitionist concepts like transformative justice and the carceral state, and thought this book could help add more language to my organizing vocabulary.

Within two pages of the first chapter, I was prompted to reflect on something I haven’t been asked to in years: “Let’s begin our abolitionist journey not with the question ‘What do we have now, and how can we make it better?’ Instead, let’s ask ‘What can we imagine for ourselves and the world?’” As organizers, we spend so much time on the logistics of planned actions that we forget to step back and dream about what the world we’re working towards will look like. Removing the imagination from the work we do can lead us to severe levels of burnout, anguish, and ultimately feeling hopeless about whether or not we can reach that liberated world.

In the first chapter alone, which only encompasses four pages, we’re being challenged to reanalyze our understanding of crime versus harm, the ways we as individuals can be complicit in the perpetuation of harmful ideologies onto other community members, practices we can engage in to lessen contact with the carceral state, breaking down the many ways the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) is thrust into our everyday lives, and most importantly, being open to change by answering that very important question, “What can we imagine for ourselves and the world?”

The question has weighed on my heart in the years since first reading the book, and especially as it relates to themes throughout the book: imagining and experimenting with strategies of community care instead of depending on punitive systems to do things that they weren’t created to do; and viewing hope as a discipline to be practiced while engaging in our fight for liberation.

We Do This ‘Til We Free Us calls attention to the generational trauma marginalized communities have experienced at the hands of the state and the cycles that continuously repeat when the majority relies on the same systems that evoke massive waves of harm in the first place. Through Kaba’s research, on-the-ground experience, and narratives from those she’s in community with, readers are shown the domino line of disappointments that the PIC and its many offspring project onto Black and Brown individuals. These sections may be eye-opening for those who believe there has to be at least some aspects of the system that are worth preserving.

In Part 3’s “We Want More Justice for Breonna Taylor than the System That Killed Her Can Deliver,” Kaba writes about the slippery slope that comes with trying to find the silver lining of the justice system after the conviction of a police officer. Arresting one cop will not eliminate the embedded systemic policies that allowed for the death of Breonna Taylor to occur. Thinking an arrest is a solution to that problem only works to validate the same system we’re trying to move away from. In her analysis, Kaba is pushing readers to see for every one occurrence where the justice system provides a sense of “justice,” there will be hundreds of other cases where there will be injustice. Why bite on our fingernails awaiting an outcome we’ve rarely been shown when we can do the work intra-communally to see what real justice, investment, and compassion look like?

Until we truly push ourselves away from the dependency of harmful structures, we’ll be forced to see different faces relapse into the same heart-wrenching stories community members and freedom fighters have been fighting against for centuries. These systems don’t guarantee us safety, at any point we could fall prey to the mosh pit of identities in which the carceral system manifests. Just because we step away from a punitive frame doesn’t mean we aren’t working toward accountability. As Kaba states, “We want to direct our energies toward collective strategies that are more likely to be successful in delivering healing and transformation and to prevent future harms.”

Hosting grieving circles, food pantries, mutual aid services, educational workshops, and creating spaces where these tough conversations can happen are just some of the strategies we can use toward those aims. In the process, we can come to see the power that lies within spaces that are led by community for fostering community power.

“I believe ultimately that we’re going to win, because I believe there are more people who want justice, real justice, than there are those who are working against that,” writes Kaba, an expression of her journey in developing hope as a practice.

It’s a rollercoaster ride doing organizing work and often you find yourself becoming quite cynical after experiencing so much loss and grief. It’s easy to put yourself on autopilot, floating by in a constant loop of actions, vigils, and City Hall meetings. It’s a routine where if you don’t find something to keep you grounded, you begin to lose yourself in it.

Being hopeless in work that requires you to create a future world where these problems don’t arise as often seems counterproductive. Hope doesn’t erase feelings of disappointment or frustration, and it doesn’t only encompass moments of joy. It’s the willingness to continue doing the work regardless of what the outcome may look like. It’s moving forward knowing a change will come either way, and you’re still working towards the end goal no matter what direction the circumstance may blow you in. It’s knowing the work doesn’t start nor end with you—we’re simply marking our particular spot of the movement timeline by laying down a foundation for those after us to follow. It’s a lifelong practice that will exist as a hovering presence while battling a tough fight.

Alycia Kamil is a multi-disciplinary artist and educator from the south side of Chicago.

In We Do This ‘Til We Free Us, Mariame Kaba writes time and time again, “abolition is not about your fucking feelings.” The meaning is simple: emotions shouldn’t cloud political commitments to the basic principles of abolition, but Kaba demonstrates that it’s more difficult to do so than it seems, even for committed abolitionists.

I experienced that difficulty in my own life. Then, in my freshman year of college, my uncle was murdered in Mexico. I saw the distress it put on my mom and two aunts living with us at the time. He was the baby in the family, nineteen years old, when it happened, only a year older than me. I felt useless at home when my mom and aunt flew to Mexico to handle the services.

When my mom came back, I learned that my uncle had been killed by another family member. That alone left permanent chills down my spine. She told me how the police in Mexico didn’t do anything to help, no arrests or investigations. If anything, they had to be paid by families to do their jobs. She said that the police were corrupt in Mexico, and I stood silent as she spoke.

After what happened, I tried to talk to my family about abolition, and my mom and I would go in circles around the idea. Sometimes I was able to change a little in her thinking surrounding prisons and punishments, but in other moments she was rigid as a steel bridge. However, I didn’t want to push her and be insensitive, I always had to talk as if walking on eggshells.

In the essay “Transforming Punishment: What Is Accountability without Punishment?” Kaba and Rachel Herzing discuss users on Twitter, including self-proclaimed abolitionists, who were happy with R. Kelly’s conviction because there was finally “justice” for his history of harm and abuse of Black women. #RKellyisgoingtojailparty was trending on the site and countless tweets were excited by the news. But Kaba and Herzing write, “Let’s be clear though: advocating for someone’s imprisonment is not abolitionist. Mistaking emotional satisfaction for justice is also not abolitionist.”

Kaba admits that her instinctual response to these situations is not always abolitionist. However, she continues to ground herself in her political commitment to abolition, constantly fighting our conditioning of punishment equating justice, because as she states, “they are systems that live within us, that manifest outside of us.”

I remember not too long ago at a family party, when I brought up abolition to my aunt, she asked a lot of questions I couldn’t answer. Still, she said that even if we started all over, not only would it not happen in our lifetimes, but we would recreate the same systems. And I was worried she was right. If “they are systems that live within us, that manifest outside of us,” how do we fight this?

When harm is done against someone you love and care about, more often than not, we want the person to be harmed, often in a worse way. In the case of R. Kelly and other famous abusers, people approve of their incarceration from a distance because it’s our measure of justice. Abolition invites us to interrogate our preconceived notions of justice and ask whether the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) eliminates harm from our world in its rendition of justice. As Kaba and others show, the answer is no; it just continues to cause more violence, an endless cycle.

In another chapter, “Moving Past Punishment,” an interview by Ayana Young, Young states how it feels irresponsible to apply a personal quest for justice to a society as the standard, and then asks, “so where is the balance between having policy and response that is both less personal but is still informed by survivors?” In policy, the response to harm is more harm, either with policing, arrests, criminal records, prison, or cruel punishments—but this only adds fuel to the fire.

Kaba mentions potential alternatives to punishment, such as removing R. Kelly and his accomplices from their positions of power and not being able to produce any more music. Another idea is that the money from his estate, including incoming music sales and streams, be allocated among the survivors. The potential for accountability outside of prison is experimental, but endless in its possibilities.

Human nature is not absent of emotion. We are allowed to feel hurt, angry, sad, resentful, and more. Mostly, we need to grieve when harm has been done, and it must be done in community. Violence does not heal wounds or the pain in our hearts, only lets them fester and blister until the hurt consumes our entire body. Wanting to hurt another because we were hurt is falling into these systems of violence. “Vengeance is a lazy form of grief,” Kaba wrote, a line I remember vividly because as much as we wouldn’t want to admit it, it is.

This chapter made me think about my uncle and what would be justice for him and for my family that doesn’t include the PIC, but I’m not sure yet. I know if I ever tell my mom about these ideas, she might get upset. I’m not going to tell my family what they should feel because we’re allowed to feel all of our emotions. One day, I’ll slowly introduce these abolitionist ideas to my family, I just don’t want them to feel like I’m trying to force them into anything.

We Do This ‘Til We Free Us doesn’t have all the answers, but it was a good start for me to think, learn, and reflect on what it means to be an abolitionist.

My practice and thinking is grounded by this section from Kaba:

“As an abolitionist, what I care about are two things: relationship and how we address harm. The reason I’m an abolitionist is because I know that prisons, police, and surveillance cause inordinate harm. If my focus is on ending harm, then I can’t be pro deathmaking and harmful institutions. I’m actually trying to eradicate harm, not reproduce it, not reinforce it, not maintain it. We have to realize that sometimes our feelings—and our really valid sense of wanting some form of justice for ourselves—gets in the way of actually seeking the thing we want.”

Rubi Valentin (they/she) is a recent graduate from the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and studied Gender and Women Studies and Professional Writing. They are a first time contributor for South Side Weekly, and is currently an editor and writer for Bonfire News.

I didn’t have the words for it. I grew up with abolitionists and organized as a teenager in revolutionary collectives, read zines at distros, and attended community abolitionist trainings, workshops at the Allied Media Conference, community meals and community political education readings. I learned abolitionist politics by living through the world created by the most caring individuals who dared to see a world where we aren’t disposable.

My commitment to abolitionism solidified when I was arrested and cops swarmed me on the ground and handcuffed me, and later when they starved me. It solidified through the money I lost just to get forced to take a plea deal and lose my most precious commodity—my time—and then pay the state $50 a month for over a year of probation. I was lucky to be around family, around community, and with an abolitionist politics that kept me grounded as the terror of the state was unleashed upon me.

Mariame Kaba’s We Do This ‘Til We Free Us gave me the words and guidelines of imagining a life where our relationships to others were the most valuable asset we have against a common enemy; a world where there is this understanding that while we are all capable of harm, we are deserving of the dignity to change; a world where there is no carceral state, where there is only us reaching for one another.

This book was a going back to basics, the perfecting of a tendu, the instructions on how-to-unfurl and strengthen my toes to create a strong base and form a solid view of the world through previously read abolitionist texts, through my lived experiences of seeing how the police terrorized my community and terrorized me. It served as the first formal text of how to maintain accountability in an actual abolitionist and taut way.

The book challenges the reader to envision a world where we are to politically uphold abolitionist principles and have designated safe spaces where it is normalized to address harms in ways that involve the community. These should be spaces where we solve problems collectively, don’t shame one another, work with both the survivors and abusers, and where we’re not separating families as the PIC does or working with the police as the NPIC does, but collectively figuring out how we can mutually get our needs and our need for safety met.

We deserve safe spaces within our communities where we make mistakes—and yes, where we address harm, because all have the capacity to cause harm. Throughout the book, this notion that none of us are exempt from that held me and gave me hope that the sooner we all realize this, the sooner we can be better with one another and the sooner we can be on our way to building a better future.

That’s how Nebula, the mutual aid organization I’m part of, was born, as a gaseous nursery full of pulsating brilliance and possibilities. It happened while I was tenant organizing. I, along with other organizers, realized that we weren’t only dealing with landlords, illegal lockouts, and the rampant inequities caused by the COVID-19 pandemic—we were also dealing with domestic violence within these family units.

We decided to create this space that wishes to collectively identify and attempt to address the root causes of harm within the community. We don’t have the answers, but we are trying to build and inspire others to build similar organizations grounded in mutual aid in their communities. We want others to build more organizations that value community cooperation, self-determination, healing, rehabilitation, and dignity.

Having a neighbor being harassed by the police can put the entire community in danger. What is the alternative? Nebula, along with the input of the community, are attempting to figure that out. We, at Nebula, are learning as we go, through lived experiences, being on-the-ground, listening to our neighbors, making art and being in community with families in crisis—collectively figuring out what needs are what it means to operate from a revolutionary love ethic.

Some of us come from the background of working directly with men who have caused harm, some of us are yoga instructors and some of us are artists and art educators that use what we’ve learned in our fields to make art in community, to express, to dance, to make beautiful things—because we have the right to heal. We make time in our lives for building and organizing because our collective liberation is of utmost importance, and as Kaba puts it, “My conviction is that we ought to be organizing steadily always. All of the time. When the protests and the uprisings happen we can meet those moments, because we’ve actually been building all along.”

It can be very isolating when going through trauma, so it’s integral to have a community around who are calm, who are compassionate and who can welcome you to your new life. A lot of us in Nebula are former survivors and former non-profit workers who understand the role that NPIC has with PIC and we have seen how this affected those people who didn’t follow the perfect victim narrative, who are criminalized, and who don’t have the resources needed to receive the help they deserve. They fell through the cracks. As we collectively envision and build that new world, we want to be ready.

In the book, Kaba writes about how her father, who is not only an important organizer in his own right but also her influence, encourages her to solve issues with one another and reminds her, “You are interconnected to everyone, because the world doesn’t work without everyone. You may think that you’re alone, but you’re never actually alone.”

Moving with dignity and working through conflict while maintaining our relationships through struggle is a seed that Nebula attempts to embed in the anti domestic violence work we do. At this time, Nebula is still in its seed stages and is at capacity. We are currently helping six families and could really use the support to grow and build our organization to add more members.

The new world is possible, it is here, and it exists, we are it, we’re all we got, and with all the love in the world, I encourage you to build mutual aid organizations, talk to your neighbors, your friends, and build stronger communities now, because we will win, we will win, we will win.

Melissa Castro Almandina is a poet & resident artist at AMFM gallery. They write poetry, make zines, & dance ballet in their spare time. Find their work online, in zines, & in The Breakbeat Poets Vol. 4: LatiNext.

It was easy for many of us to agree we didn’t like the police before we ever had the language to describe why. We saw law enforcement jammed into every crevice of our lives, creating more problems than solutions.

Many young Black and Brown folks from disenfranchised neighborhoods interact with the police for the first time early on. Whether directly, by being adultified on the street or ordered around at school, or indirectly, by seeing an adult in their life harassed during a traffic stop.

For a lot of my life, I lived at the edge of the city in a neighborhood called Beverly Woods. Here, I was part of Beverly enough to have close friends whose parents were cops, and close enough to walk to the houses of friends who those police officers did not want their children hanging out with.

My dad always preferred I hang out with kids whose parents were cops, assuming that he knew he could trust them. But why? He was afraid of the police; he tells stories of cops stopping him and roughing him up, knowing that he could not do anything because he’d recently immigrated.

He saw cops everywhere in South Shore, where we originally lived, and folks still got their cars and homes broken into. He’d never described one positive experience with a police officer, and yet always mentioned that badge when talking about my friend’s parents.

Part of me believes it was because they were Black; this created a separation in my mind as well at the time. But I started to form my own resentment toward them as adults because of the language they used to describe my peers just because they lived on the other side of the tracks.

Abolition is about more than just a disdain for policing. It compels us to understand how many of the traps designed to cage Black and Brown folks revolve around the construct of policing.

Abolitionist writing like We Do This ‘Til We Free Us is vital because, despite our desire to create a better world, the language of these movements is yet another barrier for reaching the people who would benefit from them the most. It’s hard to imagine that words like “defund” are jargon, but without the full scope of what abolition really is, people may not know they align with these ideas.

My father, like many others, does not want to defund the police despite never being helped by them. Being harmed by cops has not stopped him from thinking that there needs to be more police. This is probably because he’s also been robbed and harassed by people who look like him, so the idea of fewer police means more chances for his safety to be at risk.

That’s not what abolition is. The abolitionist framework looks to remedy the circumstances that would make a young man hold a cab driver at gunpoint in the first place—poverty, unresolved mental health issues, housing insecurity, etc.

Food and a safe place to live can stop more crime than an officer ever could considering that police show up as a response; there’s no way for them to get ahead and determine when something is going to happen before it does. Black and Brown people in marginalized communities know this already, they’ve probably seen it with their eyes, but they might not make the connection.

“Defund the police” is an abolitionist demand not only because that is where the money for these other services will need to come from, but because the police are actively harmful. In section three, ‘The State Can’t Give Us Transformative Justice,’ Mariame Kaba explains that she never calls the cops. “It takes practice to do this,” she wrote. “As such, we need popular education within our communities about alternatives to policing.”

Some people would agree that the police are not helpful, but without knowing what else to do, they might still resort to calling them. Educational materials and books that teach community members conflict resolution tactics, for example, can be the difference between life and death.

In this same section, Kaba goes on to write “…only building power among those most marginalized in society holds the possibility of radical transformation.” So by that logic, the “work” and its ideologies must be made accessible to the most marginalized.

When asked where to start on the journey to understanding abolition, justice, and liberation, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us has taken its place at the top of my list since being published. The usage of concrete examples, whether they’re providing factual evidence or detailing a personal experience, give context that allow the reader to relate their own understandings and experiences. And that’s what makes abolition tangible; folks being able to understand how it directly affects them and their communities, and why they should care about how it affects everyone else.

Literature that is as transparent and comprehensive as We Do This ‘Til We Free Us becomes a guide for individuals who have been doing the work to continually transform their thinking, and grow as well. For example, Kaba implores readers to challenge the idea that indicting police officers is a viable solution.

“Beyond strategic assessments of what is most likely to bring justice, ultimately we must choose to support collective responses that align with our values,” Kaba wrote.

“Demands for arrests and prosecutions of killer cops are inconsistent with demands to #DefundPolice […] We can’t claim the system must be dismantled because it is a danger to Black lives and at the same time legitimize it by turning to it for justice.”

To me, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us stands out as an important piece of abolitionist literature because of its writing. Kaba continues to steward important conversations and share information by creating work that is honest and understandable. It’s important that everyone is able to see how they fit into the tomorrow we are trying to create today.

Chima Ikoro is the Weekly’s Community Builder.