We are in the midst of a youth revolution & renaissance in Chicago, the beacon/center for the country/planet. Young artists & activists are using their voices & bodies & organizing abilities to change the way the city/country listens & thinks about the vibrancy & beauty of Black narratives.

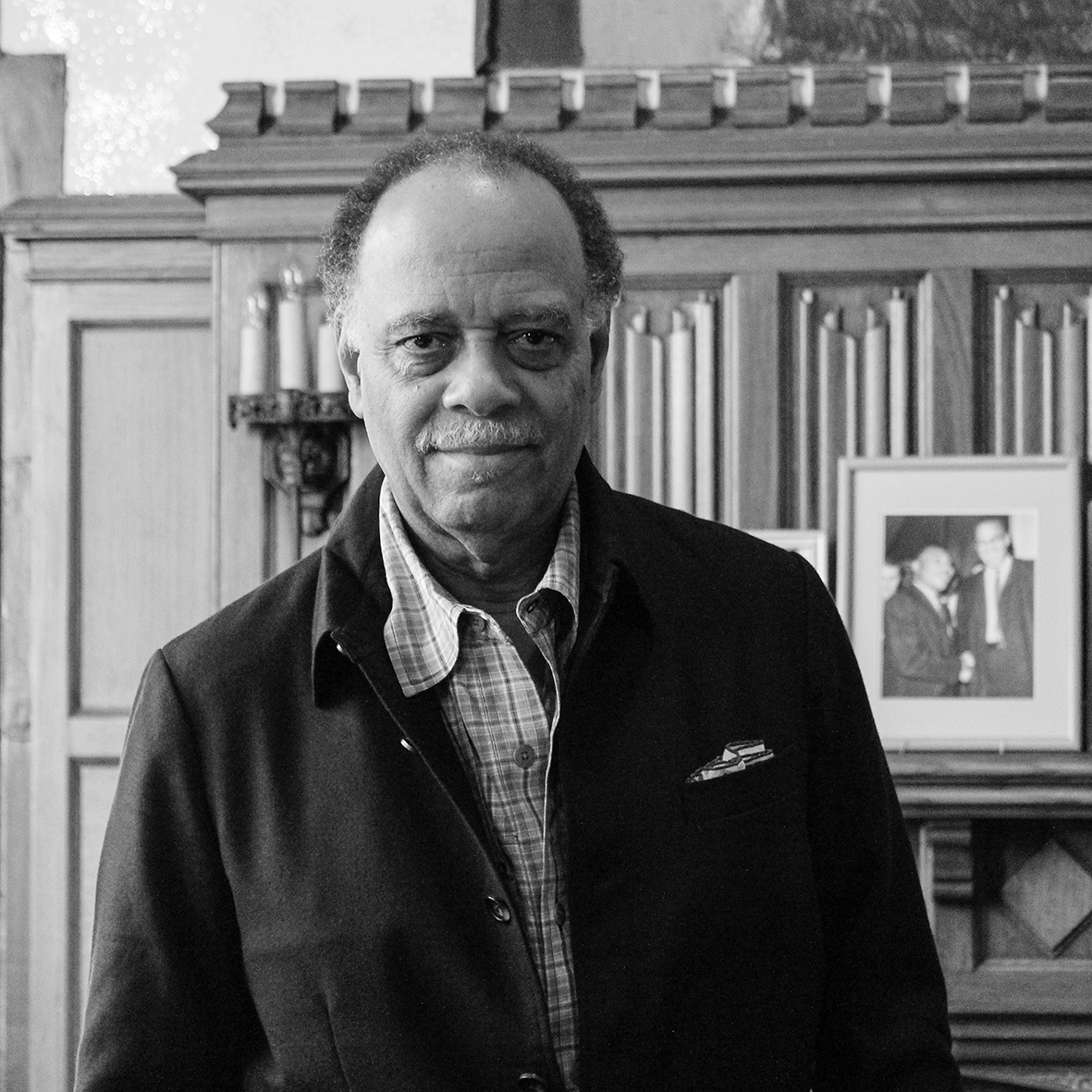

Haki Madhubuti has been doing this work as a poet & builder of independent Black institutions on Chicago’s South Side & across the globe for over fifty years. An architect of the Black Arts Movement & founder of Third World Press, a Black independent publishing house, this moment in culture would not have been possible without his contributions. Haki is the cultural son of Gwendolyn Brooks & we are the sons & daughters & inheritors of their tradition of a socially engaged, radical Black poetics that represents the working body in realist & super-realist portraiture, creating a new canon for those interested in a just & fresh future world.

We talked recently about his new book of prose, Taking Bullets: Terrorism and Black Life in Twenty-first Century America Confronting White Nationalism, Supremacy, Privilege, Plutocracy and Oligarchy. In conversation, as in the book, Professor Madhubuti drops serious gems.

Kevin Coval: This book is tragically timely. It would be impossible to plan the right moment for such a work. The origin and conception for Taking Bullets begins where?

Haki Madhubuti: I was taken aback after the murder of Tamir Rice in Cleveland, the twelve-year-old boy playing in the park with a toy gun when two policemen rolled up on him and in less than fifteen seconds he was dead. I couldn’t sleep, and in my mind it was pretty clear that if Tamir Rice were white he would still be alive. That was the genesis.

I’ve written about the plight of Black men before (most notably in the best-selling Black Men, Obsolete, Single, Dangerous?) I’m not a sociologist or a political scientist. I’m a poet. And unlike most poets, I’ve worked primarily in the Black community building institutional structures like Third World Press and the African-centered education we have at our schools, three schools, servicing over one thousand children per day.

I have been dealing with this community, all of my adult life, as a poet, as an educator, as a father; I have sons and daughters, so this subject is close to my heart. With the uptick in the killings of young Black men and Sandra Bland and Black women within our community, I felt that I cannot not say something, so I started writing and it unfolded.

KC: Taking Bullets is addressed to the twenty-first century. You worked very hard thru the later half of the twentieth century to counter white supremacy and create new Black-centered institutions. Are things getting worse for Black people now?

HM: We have to always be as honest as possible. Most white people, in the United States, are struggling and trying to live their lives, but you have a substantial number of white people, who I would call white white people. These would be the white nationalists, the white supremacists, the white-skin privileged people, even though all white people take advantage of white skin privilege at some point in their lives and might not realize it.

The problem has been, white men—not all white men, but a great many white men— still fear Black people and most certainly Black men. That fear is transmitted to the Black community, in many different ways, but the people who actually make the decisions and run things are the one percent of the ruling elite, who we would never meet for the most part. Not only do they live in gated communities, they buy islands.

KC: And I’m also thinking of the service sector, the thousands of Black people working minimum wage jobs in the Gold Coast, serving a new class of white, white collar workers.

HM: And that is where we run into difficulty, essentially police departments resemble an occupying force. You have these outliers who may have been KKK four or five years ago, but can’t be public with that stuff anymore, so they join the police department. At the same time, one doesn’t want to make the same mistake some people make with us and say all Black people are like this or all white people are like that, because it’s just not true. But one of the points I am trying to make is that these white people don’t care about white people. The right wing always wants to say we are the richest, most prosperous country in the world. If we are then why can’t we educate our children…without charging them an arm and a leg?

KC: In Taking Bullets you address these issues of empire and neo-liberalism and have made a life countering institutions of the homogenized narrative. And at times it seems we live in an eternal moment in this country, a story stuck on repeat. But the public nature of the murders of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile and others make this moment seem ripe for continued movement making, and it feels that this book, and all your books, interrupt the traditional story.

HM: Those murders were caught on tape and were undeniably murders. Keep in mind the only reason we are made aware of those murders and others is because of the technology, phones with cameras. These murders have gone on ever since our forced migration to this land.

What Black Lives Matter means to me, is that they have taken the mantle we took up in the 1960s and 1970s. The question becomes why, after fifty years, are we fighting for the same thing? Things have changed, but it is obvious they have not for a great many Black people and Brown people and poor people and people of different sexual orientations. This struggle continues.

KC: You mentioned the tool of the camera, which makes me think of the importance of the document and the work you have done in the Black Arts movement and the role of the writer, of the artist, in the movement.

HM: In the Black Arts Movement, we felt the role of the artist was to confront evil. It’s interesting that we were so young, most of us in our twenties, and just like young people of all cultures, the fear factor never entered our mind. We felt injustice existed most certainly within the context of our relationship to the people that forced us here, into this nation. This country has never been able to face its racial anxieties and syndromes. Its unevenness. Very seldom do you hear in the academy or secondary school or K-8, any serious discussion of the first genocide that happened in this nation when Europeans landed here and wiped out millions of First Nations people. And then of course they went and got Africans and raped Africa. And as long as the ruling elite and those that control the media and social media and so forth, do not confront those realities, there is not going to be any serious change.

If you don’t know who you are, anybody can name you. And they will.

One of the real serious problems is that too many people do not love themselves. There is absence of self-love and an absence of communal love. One of the formidable acts against Black people is we have been taught to hate ourselves. If I love myself and I love people who look like me, I’m not going to be killing them.

My job is, and what I’ve always tried to do since I became conscious, and I became conscious as a young Black boy at fourteen years old, was to ask, and I write about this in Taking Bullets, why do white people hate us? What did we do? I mean what did we do to deserve what we receive from the people who run this country? The question has never been asked publicly. And for me, we cannot approach that question with a victim’s mentality. In all of my work, I try to give clear alternatives to this problem.

KC: The Chicago-based and nationally-focused organizing group BYP 100’s poignant campaign is to fund Black futures. You have been building Black futures for over fifty years. What does the Black future look like to you now and how does one stay committed to building one?

HM: What keeps me going, and I think what keeps people who have been involved in the struggle going, is we have created community. We have created family. We do not see ourselves as being alone. There are very few lone wolves in this struggle—therefore we see that our backs are being covered to a large extent, and as a result of that, we do see a tomorrow in front of us. What we are trying to do in our own modern way is create independent Black institutions. It’s not enough for me to be just a poet or a writer. I have to get my hands dirty.

Kevin Coval is the editor of The BreakBeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip-Hop and author of nine collections of poems, including the forthcoming A People’s History of Chicago, out in spring of 2017 from Haymarket Books.

Structural Racism and White Privilege

It seems easy on a daily basis for the white American political oligarchy to ignore poverty and racial discrepancies. Many of our elected and clerical leaders do not speak up when excessive incarceration, arrest and traffic stop rates indicate systemic profiling, suffering and unwarranted death for Hispanic and African-Americans. (How many of these silent geniuses do or have done anything to improve employment rates for African-Americans?) By and large America’s white leaders and white majority sit silently on the blessings of invisible white privilege and pontificate about an America with “no racial inequalities.” Then … a handful of police are killed by a couple of angry “lone wolf” shooters and, lo and behold, they are instant experts on racism in America who feel free to ignore and attack “Black Lives Matter.” (The suddenness of “Blue Lives Matter” as a counter movement amplifies the truth of your assertions related to hidden white supremacism and racism among police and their overzealously angey white supporters.)

As a teacher I introduce HS students to the social science of inequality. My students independently do comparative research on specific areas of life: housing, jobs, transportation, food, medical care, child care, crime, courts, rats, roads, education, public safety, etc. They easily discover structural racial inequalities in their own community. If HS students can grasp these inequalities, why can’t we all see white privilege? My partial answer is my own biography.

Giving 1 out of 4 black conscripts combat assignments during Vietnam in the last US Army of the Draft allowed me to see a racial value problem the day we left basic combat training. Most of my white friends think that kind of inequality is past, no longer an issue of race, but one of effort. I too am tempted by such simplicity because I was poor: big family of 9 kids, divorced parents, no assets. But after 1972, I got breaks my black vet buddies did not get, and I had a poor Catholic’s good Jesuit HS education to help me survive college. If you can’t access, handle or sustain participation in college, it’s not real opportunity. I watched a lot of my vet brothers drop out: poor white and black. Check the stats. I began to see white privilege as the support of leaders, teachers and employers who will help a white stranger before they’d help a black stranger. (And white police sending me home a few times with a warning, not an arrest!) Mostly, white business people would throw part time work my way–Jobs, the golden ticket. Sure, I didn’t fit in everywhere due to poverty, wrong clothes, lack of golf and tennis lessons, but I could “pass” in most job situations because I am white. If I wasn’t treated well or better, I wasn’t constantly viewed as “less than” (which I discovered when white supervisors shared evaluations of my black peers to assess my white-ness.)

Why does race blind us so? Most of us white folks take our privilege for granted. We cannot see advantages, especially if we’re poor whites from broken families lacking support. We know what it’s like to work 2-3 jobs, go on food stamps, fail to pay med bills and default on student loans, so we get so absorbed by our own struggles to create opportunity for our own families. We ought to have more empathy for the poor, for the complaints of people of color who carry water for the Man, but we just don’t. We see our struggles as separate, but equal. We just can’t imagine the weight of 2 centuries of racism added to our burdens. We want a better America that offers the dream of prosperity and assume others will get it too, if they try and work hard. We assume a failure to succeed is a failure of effort or character, but a white man still gets more unnoticed and often subtle options, windows of opportunity. We should be more realistic about our gifts, our breaks, our head start, our white privilege, but instead we’ll embrace the suck and see an empty promise of making America Great Again as our way forward. “Why’s that ‘great’ America pretty much just an old white America of a rising middle class past that’ll never come again? Why don’t we demand an America that shares and includes all because diversity is our strength? Why can’t we focus on how black lives matter so that we can truly see how all lives matter?

I came to the AA-like Step of seeing racism as a problem beyond my control due to an intervention in the form of the Draft. I see others beginning the journey through justice education, social activism and celebration cultural contributions through the arts. Your voice and the Renaissance you mentor are indispensable for our survival and transcendence. Thank you!