This series was a finalist for the 2018 “Best Feature Series” in a non-daily newspaper or magazine Peter Lisagor Award from the Chicago Headline Club

The second in a series on pretrial detention

Lavette Mayes, a mother from the Southeast Side detained pretrial for her inability to pay bail, spent fourteen months in jail before being bailed out. Along the way she received two bail reductions. At the second, the judge assessed Mayes’s bail at $95,000, meaning she would have to pay $9,500 to be released. Though this would have been an affordable bond when Mayes was first arrested, she was no longer able to pay this amount, as much of that money had since disappeared in attorney’s fees and other incarceration-related expenses.

“People’s assumption is that jail is free,” said Mayes. “It’s not. When you’re in jail, there are so many different things you have to pay for, like phone calls, which are extremely expensive. It put a lot of strain on and took a toll on my family.”

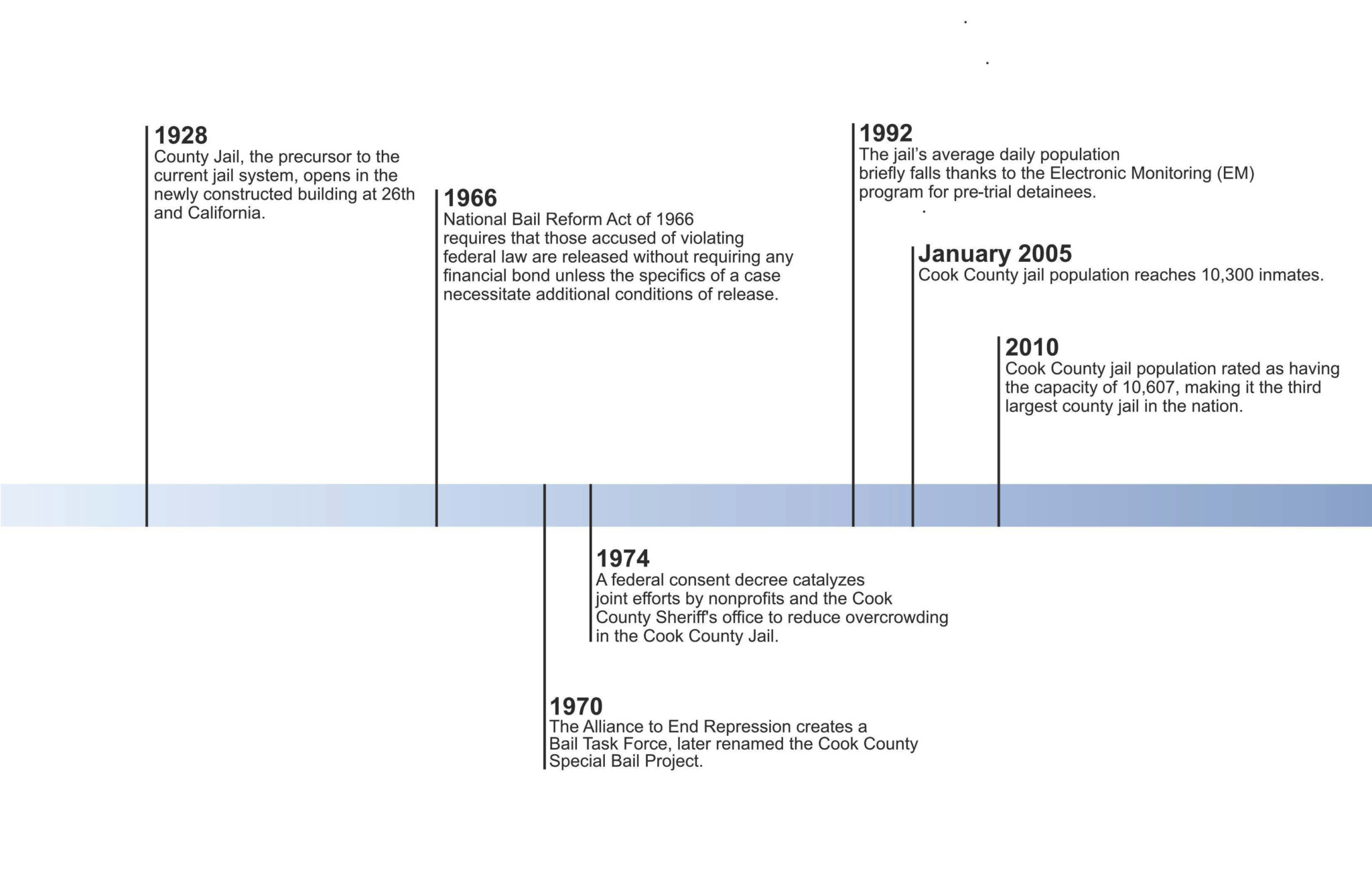

In the last few years, a seismic change has occurred in Cook County’s bail system. This change follows organizing efforts from the Alliance to End Repression in the 1960s and 1970s. Thanks to the continued and relentless work of activists, Cook County comes closer to ending the practice of monetary bail every day.

Previously, the Weekly looked at the history of bail and reform movements in Cook County. We now turn our attention to the more recent past regarding both the grassroots organizing efforts to reform the bail system and more formal legal action.

After nearly a year in jail, Mayes received a visitor who gave her information on a community organization that helped post people’s bond in Cook County. “At first, I didn’t believe it, because my family had tried to call several places about help posting bond. They didn’t have any luck, they were spinning their wheels basically,” Mayes said. As she soon found out, the organization that the visitor mentioned to her was the Chicago Community Bond Fund (CCBF), a nonprofit group that helps people facing pretrial detention in Chicago post bails that they could not pay.

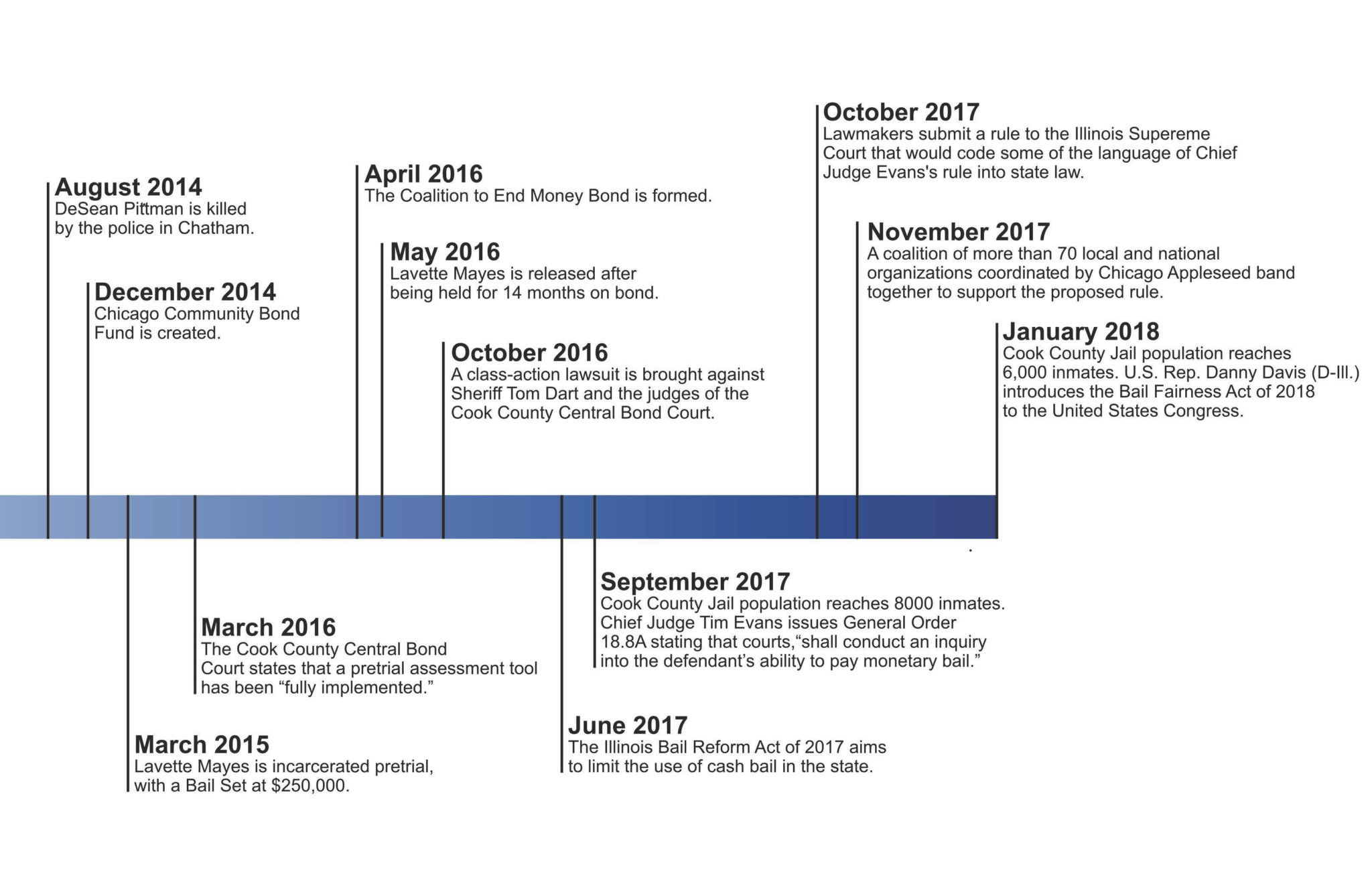

On the evening of August 24, 2014, DeSean Pittman was killed by police in Chatham. Three days later, as Pittman’s family and friends held a vigil to honor the seventeen-year-old, police showed up and began kicking over memorial candles, ripping down memorial posters, and taunting the crowd that was gathered to mourn Pittman. The police ended up arresting eight people at the vigil, five of whom were detained with felony charges of mob action and aggravated assault.

One of them was Pittman’s mother, thirty-four year-old Natasha Haul, who was held on $75,000 bail, an amount well above her ability to pay and would have prevented her from attending her son’s funeral. In all, it would cost Pittman’s family and friends $30,000 to get all the people arrested and detained after the vigil out of jail pretrial.

Max Suchan, a law student working with the National Lawyers’ Guild at the time, read about the police ambush of Pittman’s family and friends at his memorial and reached out to the family to see if they needed support in light of the arrests. He also sent a letter to nineteen-year-old LaKendra Lottie, who was arrested at the vigil and was being held in the Cook County Jail on a $100,000 detainer, requiring her to pay $10,000 to be released.

Lottie hadn’t even been at the vigil when she was arrested. She drove her siblings, who knew Pittman from school, to the memorial and was waiting to drive them home when police approached her and allegedly started beating on her car, breaking the back window and shouting, “move on, move on.” As she was driving away, LaKendra tapped one of the officers with the vehicle. The police immediately charged her with attempted murder and took her to the Cook County Jail.

“When we found out her bond, we [knew we] just didn’t have that type of funds,” said Elzora Threets-Lottie, LaKendra Lottie’s mother. Lottie mailed the letter Suchan had sent her to her parents, who invited Max and Jeanette Wince, the mother of twenty-six-year-old Derrick Wince, who had also been arrested at the vigil, over to their house to talk about getting Haul, Wince, Lottie, and eighteen-year-old Davontae Ruth released from jail.

Wince, Threets-Lottie, Suchan, and other organizers started raising money through methods ranging from online fundraisers to raffles and fish fries. The organizers raced against the clock, and eventually Haul was bailed out the day before her son’s funeral. “It took us a really long time, it took us three months to get LaKendra out,” Suchan said.

The last person to be bonded out of jail was Wince, nearly four months after the vigil. By that time, irreparable, unnecessary harm had already been done to Wince, Haul, Lottie, and Ruth’s lives. Ruth had to repeat his senior year of high school, Lottie lost her job, and Haul struggled to maintain childcare for her two young children while losing her job and nearly missing her own son’s funeral. While Suchan was focused on the immediate aftermath of Pittman’s death, Jeanette Wince and Threets-Lottie were already thinking about how to prevent this type of harm in the future.

“It was really heartbreaking to see our daughter like that because none of them should have been in jail in the first place just because they went to pay their respects to their friend,” said Threets-Lottie. “When they locked her up, it was like they locked me up at the same time. We wanted to start something so people who were in the situation we were in would have help to support their children.”

“The Fund would not exist without Elzora and Jeanette,” Suchan agreed. “They really pushed us to dream and think bigger than anything we thought was possible.”

What began as a successful campaign to bond Haul out of jail in time to attend her son’s funeral and to get the others released pretrial soon turned into the creation of the CCBF. A few weeks after posting Derrick’s bond in December 2014, the Bond Fund had its first official organizing meeting with about a dozen attendees.

“The initial conversations…were all around whether or not the Fund would be just a general fund for anyone who needed help with bail or whether it would be a more of an activist bail fund for people facing politically motivated charges,” said Sharlyn Grace, an activist who helped organize the bail fund and a Senior Criminal Justice Policy Analyst at Chicago Appleseed Fund for Justice. The organizers ultimately decided that it would serve both functions. At the time, only four or five other bond funds existed in the United States. Now, almost thirty funds exist in states across the country.

The Bond Fund uses a set of eleven interactive criteria to determine whether to pay bond for someone who asks for assistance. These criteria detailed in their 2017 report include factors such as “anticipated impact of detention on applicant’s employment, housing, educational attainment, and/or custodial rights” and “position in relation to structural violence, community disinvestment, systemic racism, survival, and resistance.”

To date, CCBF has posted 121 bonds, engaged with broader criminal justice reform efforts, and advocated for individuals who have not been treated fairly by the justice system like Paris Knox, a Black woman who was jailed for ten years for defending herself against an abusive ex-partner. Due in part to the work of organizers with the Fund and activists from dozens of organizations around the country, Knox was released from prison a few days ago.

With about seventy volunteers and three paid employees, the Bond Fund’s true goal is to put themselves out of business. “We were really clear from the first meeting that we didn’t want to exist,” Suchan said. “The idea was not to create a fund forever to post these bonds, the idea is that no one should be in jail pretrial in the first place.”

There is no typical volunteer experience within the Bond Fund. Volunteers post bonds, organize events to fundraise for the fund, write grant applications, meet with key policymakers, create bond-related educational materials, plan public events to raise awareness around the issue of bail reform, run intake appointments, and much more.

“I think it’s really important for people to know that we’re not a guilt or innocence-based bail fund,” said Grace. “We don’t ask for any information on anyone’s case. Everyone is presumed innocent, we don’t worry about charges. We’ve posted for people charged with misdemeanors that are really petty things and we’ve posted bond for multiple people accused of murder.”

In the spring of 2016, the Chicago Community Bond Fund joined a monthly convening of advocates interested in reforming the use of monetary bond in Cook County coordinated by the Chicago Appleseed Fund for Justice, an organization that has been working on bail reform for over a decade.

“Though it’s called the Coalition to End Money Bond, we work within the framework of criminal justice reform here in Cook County to more broadly end the disproportionate effects that our policies have on poor people and people of color,” said Chirag Badlani, a partner at the law firm Hughes Socol Piers Resnick & Dym and a member of the Coalition. “We think broadly around the way that our system of pretrial detention, pretrial services, and monitoring people in and out of custody affects these communities.”

The Coalition to End Money Bond, which drafted and organizes around a set of principles for bail reform in Cook County, also includes other organizations such as A Just Harvest, the Illinois Justice Project, Justice and Witness Ministry of the Chicago Metropolitan Association Illinois Conference United Church of Christ, Nehemiah Trinity Rising, The Next Movement, The Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, Southside Organized for Unity and Liberation (SOUL), and The People’s Lobby.

“We have folks that can organize community members, we have folks that are versed in law and policy, we have folks that can write a bill,” said Ted Miin, an organizer with the coalition as a part of A Just Harvest. “One of the things that the Coalition to End Money Bond does so well is having a balance of policy and legal folks as well as community organizations at the table. It’s comprehensive and holistic.”

Its diverse set of members brings a variety of organizing strategies and targets to end the practice of money bond in Illinois for once and for all. “We’re working on moving the judges, the governor, the Illinois Supreme Court, everyone, asking [ourselves], ‘What can have the quickest and biggest impact? What can have the most lasting impact?’” Miin said.

The Coalition connects community members who have been impacted by money bond to legislators and policymakers who have the power to change the bond system. It has also collaborated on legislation that would help end the use of monetary bond in the city and state and organized demonstrations to put pressure on public officials and raise widespread awareness about the unconstitutional use of monetary bond in Chicago. Its efforts also include coordinating teach-ins and courtwatching trainings around the city, collecting and analyzing data on improper use of bond in Cook County, and organizing around the upcoming elections for judges and governor in Illinois.

Organizers with the coalition believe that grassroots movement building goes hand in hand with formal legislation. “If we’re not doing that movement-building, we spent a year making a lot of Springfield trips, we get a bill out, we get a cosponsor list,” Miin said. “Then [Illinois Department of Corrections] or someone with a backdoor relationship with someone on the committee does something outside of our control. The bill never makes it out of committee, and suddenly we’ve spent a year doing this work and there’s almost nothing to show for it.”

To this end, the Coalition has worked to bring the issue of bail reform to the attention of more Chicago residents and outlets like the Tribune, which recently published a piece on the bail reform efforts in Cook County.

“Bail is an issue that can feel ‘out of sight, out of mind,’” Miin said. “Through our courtwatching initiative, we had a hundred-plus volunteers who learned about mass incarceration and how money bond contributes to it…Having more awareness around the issue means it’s less work to start that conversation with public officials and the community members they serve.”

Through it all, the Coalition’s top priorities are centering those impacted by the criminal justice system and excessive bail in their efforts and organizing so that people who are directly impacted by bond implementation can have an avenue to be self-advocates.

“We don’t want to use people,” Miin said. “A Just Harvest’s engagement with this coalition was something that was highlighted by our community as, ‘this is something that is affecting us every single day.’”

“Reformers sometimes think about these things from a very academic or research perspective, but we have to remind ourselves that these principles and the way we use them in our courts has an impact on individuals and families and communities,” added Badlani.

For Miin, Badlani, and other members of the Coalition, one of the biggest signs of its efficacy is the sheer reduction in the amount of pretrial detainees in Cook County Jail since the Coalition started pressuring influential criminal justice stakeholders to take action. “Cook County Jail is at about 6,000 people right now. Five months ago, it was at 8,000. We’re down 25% for people who should never have been in jail in the first place,” Miin said. “That’s why I do it, that’s the biggest win. That would not have happened without the public pressure and work of the End Money Bond Coalition.”

By the spring of 2017, in part due to organizing efforts like those from the Coalition to End Money Bond, bail reform had become a hot topic nationally and locally, with many excited to amend a system that had seen little change in decades. Many bills were proposed in Springfield that would change the cash bail system in the state in ways big and small. Criminal justice reform and other progressive policy groups led by the People’s Lobby came together to work with State Representative Christian Mitchell in writing one of these proposed bills.

“We thought that was really the most progressive bill out there,” explained Sharone Mitchell, a former public defender and Deputy Director of the Illinois Justice Project. Though many of the proposed bills recommended limiting cash bail to amounts that people could afford, Mitchell’s bill uniquely proposed ending the use of cash bond altogether with provisions for data collection and monitoring.

In all, the state was inundated with nearly twenty bills covering bail reform, spanning small tweaks to big changes that affected the entire criminal justice system. Eventually, elements from State Rep. Mitchell’s bill were combined with principles from the seventeen or eighteen other proposed bills and recommendations, resulting in the Illinois Bail Reform Act of 2017. The Illinois bail statute now requires that pretrial conditions should be,“the least restrictive necessary” to assure attendance in court and protect the integrity of judicial proceedings.

However, the Bail Reform Act lacked a lot of reforms many saw as priorities for improving the Illinois bail system. “The Act was much more symbolic in its strength, it kind of was a restatement of the current law,” said Mitchell of the Illinois Justice Project. “It was a small step forward, but it wasn’t a transformational piece…we still consider it a victory because at one point, it seemed like there was potential for moving bail reform backwards through this legislative process.”

While State Rep. Mitchell’s bill met significant resistance from some state legislators whose jurisdictions more heavily relied on the fees collected from cash bail to help fund their criminal justice systems, the proposal found a supporter in Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart, a vocal critic of money bond. In November 2016, Dart made a public announcement in support of the abolition of cash bail. A year later, with significant reform efforts underway, Dart echoed this sentiment in an address to students at the Harris School of Public Policy, stating that the most crucial change necessary in the Cook County criminal justice system is the end to the practice of having money as a factor in pretrial detention.

Other public officials have also stated their commitment to ending cash bail and reforming the Cook County criminal justice system. State’s Attorney Kim Foxx announced in March that her office would stop opposing the release of some detainees because they could not afford small amounts of bail, stating, “There is often no clear relationship between the posting of a cash bond and securing the safety of the community or the appearance of a defendant.” Though this change would only impact a few dozen of the thousands of detainees in Cook County, it is a step in the right direction from the State’s Attorney’s office. Commitments like these, along with the vocal support of bail reform from Cook County Public Defender Amy Campanelli and Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, have helped drive the momentum for abolishing cash bail.

At the state level, Illinois Supreme Court Chief Justice Rita B. Garman, State Representative Carol Ammons, and Administrative Office of Illinois Courts Director Mike Tardy demonstrated their commitment to improving pretrial justice on October 26, 2016 by joining Three Days Count, a national campaign led by the Pretrial Justice Institute to end money bail and restrict detention across the country.

“The name really explains the campaign,” said Grace. “After three days in custody, the negative effects really start to accumulate,” since incarceration can put people’s jobs, housing situations, and relationships in jeopardy. These negative effects are apparent in Lavette Mayes’ case. Due to the fourteen months she spent in jail and the resulting loss of income, Mayes lost her home and the vehicles she owned in her transportation company. Additionally, Mayes almost lost custody of her children due to her pretrial incarceration.

“The most heartwrenching part was feeling like my kids were being hurt by their mother being locked up,” she said. “When you’re incarcerated, the whole family is incarcerated. You’re not there as a parent. I missed their graduations, first days of school, being there for my kids.”

Despite his recent pro-bail reform rhetoric, in October 2016, Dart found himself on the receiving end of a Illinois State Court class-action lawsuit along with the judges of the Cook County Central Bond Court. Filed by Hughes Socol Piers Resnick & Dym, the Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center, and Civil Rights Corps, the lawsuit Robinson et al. v. Martin et al. contends that “the Cook County circuit court judges and Sheriff Tom Dart are violating the constitution by illegally setting bond that poor people cannot pay and then holding them in jail while they await trial,” infringing upon arrestees’ right to pretrial liberty.

“Bail can be both reasonable and unreachable. It doesn’t matter how ‘low’ your bond is if it is still above your ability to pay,” said Alexa Van Brunt, a lawyer working on the case through the MacArthur Justice Center.

The litigants are no strangers to bond reform. More than a decade ago, Locke Bowman, the impetus behind the case, and another lawyer with the MacArthur Justice Center brought a lawsuit challenging the use of video conference proceedings in bond hearings.

This lawsuit was eventually settled, resulting in video bond hearings being replaced with in-person hearings, but Bowman’s interest in bond reform remained. Upon analyzing data on pretrial detainees in the Cook County Jail, Bowman discovered that African Americans were more likely to be locked up pretrial for the inability to pay bond than white defendants. Due to their increased likelihood of being detained pretrial, black defendants were more likely to plead guilty or to be convicted than their white counterparts and were more likely to get harsher sentences. As a result, Bowman started looking again into litigation to reform the criminal justice system, working with the Coalition to try to attack the money bail system from a new angle.

One of the named defendants in the 2016 lawsuit, Zachary Robinson, waited in the Cook County jail for nearly a year while legally innocent and awaiting his trial. He and Michael Lewis represent 4,000 people in the Cook County Jail who are behind bars solely due to the fact that they were assigned a bail they could not afford.

Van Brunt and the other lawyers seek a declaratory judgment from the Chancery Division of the Circuit Court of Cook County declaring the current monetary bond practices unlawful rather than seeking a particular remedy. “When you seek damages, all you’re entitled to is money for past suffering, you don’t have the right to change the system going forward,” she said. In this lawsuit, Van Brunt and other litigators want to change the system for everybody in Cook County.

Dart’s office was eventually dropped from the lawsuit by the plaintiffs in an effort to focus on the bond court judges, who have the greatest power in the setting and administration of bail. Nationally, similar lawsuits have resulted in the abolition of cash bail in seven local jurisdictions across the country.

According to Van Brunt, litigation is just one of many forms of activism the Coalition has pursued in order to cement the cultural shift around money bail in a lasting and enforceable law. “There might be some changes now, but if we make it discretionary or a recommendation, which is currently what the law is in Illinois, history shows that judges will not follow those recommendations,” she said.

According to the Tribune, Judge Celia Gamrath “took the case under advisement” and plans to rule later as to whether or not the suit will go to trial. “We’ve been in a bit of a holding pattern,” Van Brunt said, laughing. “The judicial defendants…moved to dismiss the case on various grounds,” arguing that recent developments, including General Order 18.8A from Circuit Court Chief Judge Tim Evans, which tries to reduce using monetary bonds, make the potential decision unnecessary.

But results of the Order are mixed. While the number of unaffordable bonds has decreased, thousands are still in Cook County Jail solely for their inability to pay bail.

Judge Evans’s Order and the continuing problems of the bail system in Chicago are the focus of the final installment of this series on bail reform

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

Thank you for the thoughtful, thorough article. I look forward to the next installment.