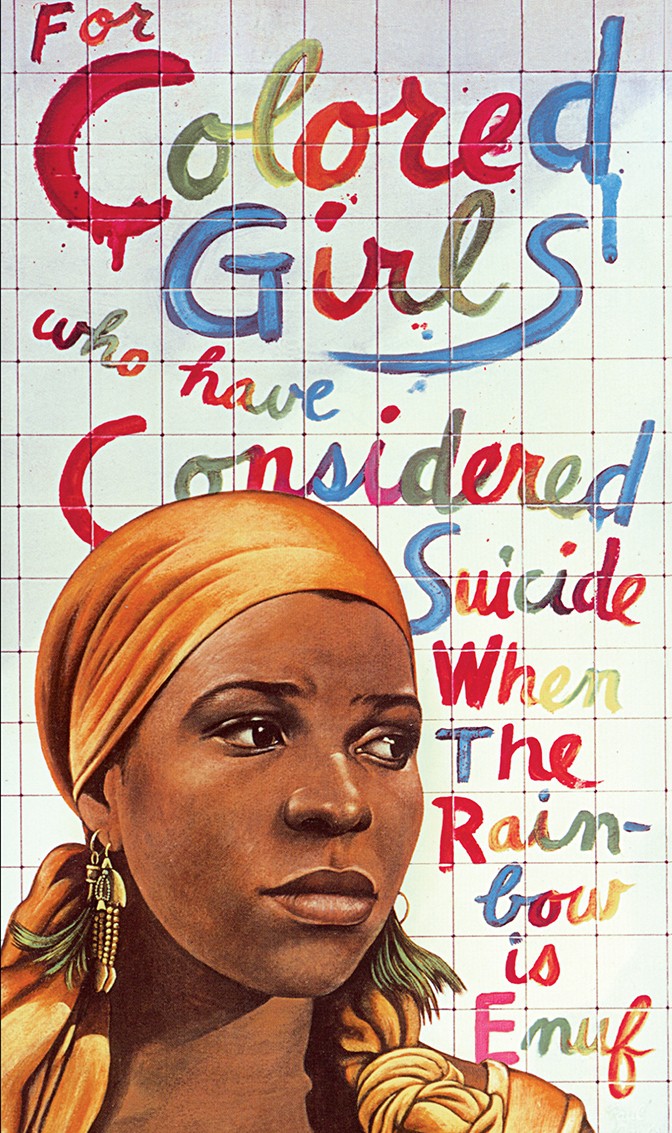

Black women across the globe of a certain age have either read, watched, auditioned for, or performed in some iteration of playwright Ntozake Shange’s award-winning classic choreopoem For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When The Rainbow Is Enuf. Now through April 14, Court Theatre brings to the stage impeccable professional production quality, a director who performed in the original 1976 Broadway production, and a multitalented cast—plus all the heart one can hold—in the show’s current iteration.

The choreopoem—a genre coined by Shange in the 1970s when her production first opened on small intimate stages before moving to Off-Broadway and then on to Broadway—incorporates, poetry, movement, and music into the traditional stage play. For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When The Rainbow Is Enuf, (yes, the work’s full title, not to be confused with the Tyler Perry movie adaption simply titled For Colored Girls) is not a drama, not a musical, not a dance performance, not a poetry reading. Nor is it a comedy or a tragedy, in the classical sense. It is an amalgamation of all, spun into an experience only to be understood by becoming part of it. As Shange remarked in the forward to the 2010 second printing of her classic work, “As for me, despite the remarkable experience, exposure and opportunity theater has given me, my roots remain firmly grounded in the fertile hallowed ground of poetry, random poems dictating their own course.” Audiences become a part of that course, driven by the lives of the eight women who comprise a melanated rainbow on stage during each performance. This is not done by some interactive mechanism, but rather by the sheer force of Shange’s stories.

Ntozake Shange, born Paulette Williams in Trenton, New Jersey in 1948, earned an M.A. in American Studies from the University of Southern California in 1973. She changed her name in 1971 in order to reflect a newfound personal strength, a triumph over difficult years, and a reclaiming of her identity and its African roots. The African Xhosa dialect translates Ntozake to mean “she who comes with or into her own things” and Shange to mean “she who walks like a lion.”

The stories Shange tells do bring their own things: love, honesty, playfulness, sensuality, sexuality, fear, frustration, pain, comfort, joy, and friendship, all told with the bravery of a lioness. They are the grown folks stories that are told and have been told by women, in the company of women, for generations—earthy accounts that, when told, little Black children knew to stay in their places, far away from kitchen tables or beauty shop chairs, when their mothers and aunties and their sister friends were talking, reminiscing, consoling.

The choreopoem’s initial iterations were fraught with pushback from many Black men (and some women) who asserted Shange’s work depicted them unfavorably by publicly airing a dirty laundry of sorts. But the stories are what the stories are, each born from a woman who lived in a women-centered world, taught women’s studies, and belonged to women’s cultural and political groups. Many of the stories were inspired by true occurrences. Had audiences paid better attention during the work’s earliest iterations, some of the self-righteous indignation touted by Black men over Shange’s subject matter belonged to white men as well. The nineteenth century Quadroon Balls, for example, which Shange describes in the poem “Sechita,” and audiences get to experience through the sultry choreography of Leah Casey as the Lady in Purple, were cotillion-type soirees held during slavery and post-slavery, for the express purpose of white men selecting fair-skinned mixed-race Black women for long-term, often contracted sexual encounters, despite the legal contracted sexual encounter of marriage between the races being outlawed.

What can be described as the most painful poem in the collection—sorry, no spoilers here—and delivered hauntingly by AnJi White as the Lady in Red, was inspired by an incident Shange glimpsed while stuck in a traffic jam. She subsequently read three news stories in the back pages of the New York Post describing identical violent incidents. Some of the poems are traumatic, and all of the stories are true for someone, somewhere.

Interestingly, the places in the choreopoem which some deemed as man-bashing over forty years ago—when they were spoken of only in private among women, or on the very back pages of newspapers—are the places which detail painful life episodes now making front-page news. Date rape, spousal abuse, child abuse, infidelity, and objectification of the female body are all stories with men often as the villain, but Shange’s work never asks a man to wear a shoe that doesn’t fit. After all, the choreopoem’s chief aim is to sing a Black girl’s song, not the song of anyone else.

Director Seret Scott, who was cast in the original Broadway production and who also directed Court Theatre’s 2011 production of the Zora Neale Hurston play Spunk, brought audiences a final gift from the playwright before her passing in October 2018: permission to add a new character to the rainbow. Shange’s original rainbow, comprised of seven women sharing points of view from outside of various cities, now weaves the poems and their transitions together sometimes using the voice and music of Scott’s vision of an eight character. Lyric, from “outside Chicago Heights” and expertly played by Melody Angel, adds a new fluidity to how Shange’s poems connect to themselves. All of the ladies are captivatingly brave in their artistic choices. Each woman on stage is quite literally poetry in motion. For audiences who will see For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When The Rainbow Is Enuf for the very first time at Court Theatre, this iteration will be the show they will never forget. And for those who have seen this classic work before, this will be the iteration they will always remember.

Nicole Bond is the Weekly’s Stage & Screen Editor. She last wrote for the Weekly in September, reviewing the Court Theatre production Radio Golf.