In March 2020, Patrick Malia, then thirty-seven, left work on Friday feeling under the weather. He spent the next day shivering so hard his bed was shaking. When he got to the emergency room, he had a 104-degree fever and a hard time breathing, especially with his asthma. As the hospital filled with coronavirus cases, he was sent home. His doctor didn’t think he had COVID-19 but was afraid that he’d catch something worse by being there.

Malia didn’t know it then, but he first got infected with the coronavirus at the beginning of the pandemic. At the time, testing was only available by a doctor’s order, and Malia’s doctor was convinced he didn’t have it. He stayed home without knowing what was wrong and kept away from his family, but he never seemed to recover.

“I stayed in the house for thirty-eight days. I didn’t leave the house,” he said. “I couldn’t walk more than ten feet without collapsing…I couldn’t lie down and sleep because I couldn’t breathe, so I slept in the recliner for three weeks sitting up.”

The world looked completely different when he left the house again. He saw a pulmonologist, who told him he had every symptom that other hospitalized COVID patients were experiencing. But without a positive COVID-19 test, he struggled to get a proper diagnosis for a long time.

He was navigating a maze of doctor visits, seeing different specialists for fatigue, heart issues, and migraines, and trying to figure out what was causing it. Tests came back negative for Epstein-Barr Virus, mononucleosis, and other diseases that matched his symptoms. He ended up taking six months off from his job as a technician at a surgery center, and when he went back to work, his symptoms made daily tasks more difficult.

“I was basically unrecognizable to everyone. I was the one everyone relied on to help out and jump in. I could do fifteen things at once,” he said. “Then there’s me that comes back, hobbling down the hallway and getting winded by standing up.”

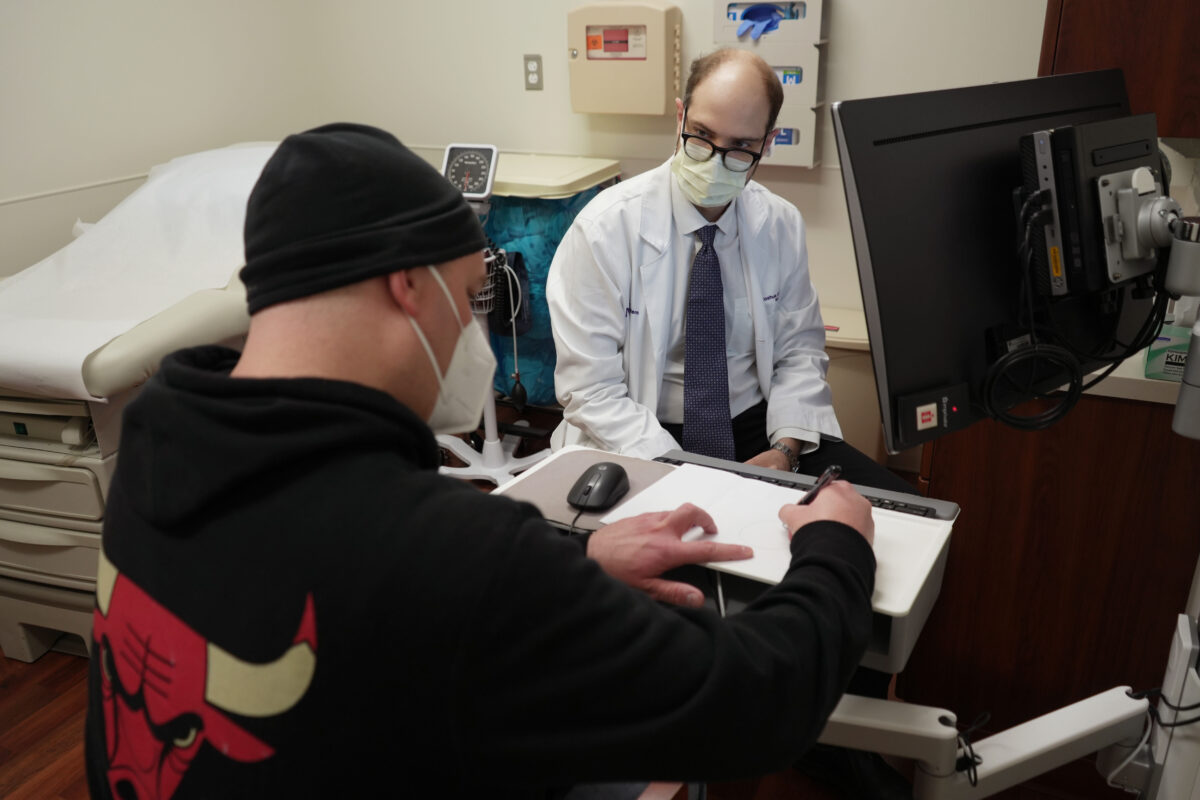

It wasn’t until he’d gotten an appointment at Northwestern University’s long COVID clinic that he felt things start to change. Talking with Dr. Marc Sala was the first time he felt his symptoms were truly heard.

“He spent a full hour with me to talk about everything you could imagine,” Malia said. “The first thing he said was, ’I believe you.’…That’s what I needed because I was almost starting to believe that I was losing my mind. I couldn’t explain how I could get short of breath by standing up and getting a drink of water, but it was happening.”

Malia spent the next year going to the clinic regularly for help with day-to-day functions and cognitive rehab at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab. Occupational and speech therapy helped him learn how to adapt when his brain fog or forgetfulness started to flare up. He knows to rest up in advance if the next day looks like it will take a big physical or mental toll. But COVID didn’t fully leave him.

“I’m looking to work my way out of healthcare because I can’t physically do it anymore,” he said. “To be on my feet all day, every day, running from one place to another, moving patients, moving heavy things. It has taken such a toll on me physically that, right now, I’m just trying to figure out what to do because I know that I can’t do this anymore.”

Northwestern Medicine’s Comprehensive COVID-19 Center was the place where Malia first learned how to manage his symptoms. Sala, a pulmonologist and critical care specialist, co-directs the clinic. Established in the summer of 2020, it became one of the first to treat patients with lingering symptoms of the virus, such as brain fog, shortness of breath, and chest pain.

“There’s no predictive strategy to know if you’re going to develop persistent symptoms….Even if we’re not dealing with ICU-level illness, we still have a huge number of people who have symptoms after their infection that they didn’t kick,” Sala said. “We have a complete lack of answers about how to help those situations.”

“It’s finally hitting an inflection point where we’re going to come up with strategies to heal people faster from these conditions.”

Since 2020, the United States has seen more than 100 million reported COVID-19 cases. But even after the acute phase of the illness passes many still deal with its symptoms long after infection. That year, patients coined their lingering symptoms as “long COVID,” describing their often-disabling symptoms in forums and patient-advocacy groups online. In 2022, the American Academy of Neurology declared that long COVID was the third leading neurological disorder in the United States.

“The history of long COVID and the focus put on it was very much a grassroots effort from patients…It led to providers such as myself needing to take it more seriously and pay attention,” Sala said. “It’s not uncommon for me to see people in the clinic who have just seen three or four doctors who said that it would be much more temporary or the worst case, it’s all in your head, which is always disturbing to hear.”

Even after the body clears the virus that causes COVID-19, many people continue to have symptoms or develop new health issues afterward. One in four adults who contracted COVID-19 reported having experienced long COVID in 2023, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. Anywhere from 7.7 million to 23 million Americans have developed long COVID at some point during the pandemic.

Since the pandemic’s onset, several long COVID clinics have popped up at universities and hospitals. As of 2022, sixty-six health systems nationwide have post-COVID-19 care clinics, including several in Chicago. UChicago Medicine is currently the only clinic operating on the South Side.

Long COVID clinics emerged as a “one-stop shop” for patients who may be managing many different kinds of symptoms due to the virus. For Malia, having all these resources in the same place made it easier to seek care.

| Clinic Name | Address | Contact Information |

| Humboldt Park Health COVIDClinic | 1044 N. Francisco Ave, Chicago, IL, 60622 | Phone: 1-888-624-1850More information. |

| Neurology COVID Clinic at Loyola Medicine | Multiple Locations | Phone: 1-888-584-7888More information. |

| Northwestern MedicineComprehensive COVID-19Center | Multiple Locations | Phone: 1-312-926-9900More information. |

| UChicago Hospitals Post-COVID Recovery Clinic | 5841 S. Maryland Ave, Chicago, IL 60637 | Phone: 1-773-702-6840More information. |

| UI Health Post-Covid Clinic | 1740 W. Taylor St,Chicago, IL 60612 | Phone: 1-312-996-9334More information. |

Long COVID is not well understood, despite its prevalence. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) identified more than 200 long COVID symptoms, including extreme fatigue, cognitive impairment, post-exertional malaise, and respiratory symptoms. More severe infections are more likely to result in long COVID, but it’s not a one-size-fits-all disease for people, so piecing these symptoms together becomes challenging.

Dr. Leonard Jason is a psychology professor at DePaul University. His work studies long COVID through the lens of other chronic fatigue syndromes, finding a lot of similarities between long COVID and Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), another debilitating condition that lacks clear diagnostic tests.

“Medicine is good at helping people with clear-cut disorders…What medicine isn’t good at is these types of unexplained disorders,” Jason said. “Primary care doctors are not great at figuring out how to deal with these chronic conditions that affect so many people.”

Over a year later, while studying long COVID and ME/CFS symptoms, he found many similarities between them.

“People with long COVID over the years generally tended to get better than people with ME/CFS,” Jason said. “What that suggests to us is, a number of people with long COVID, over time, will begin to get better, and some will completely get better. But some will maybe not completely but be pretty functional. Those who basically continue to be sick and very impaired will probably transition into the category of ME/CFS.”

One of the current theories behind why people get long COVID is that their bodies cannot completely clear the virus and stay in a state of chronic infection that flares up from time to time. It could be similar to how the Epstein-Barr virus can stay dormant in the body and reactivate to make someone ill again.

Some researchers have zoned on microclots in long COVID patients’ blood which block the flow of oxygen to critical organs. Others believe the infection destabilized their immune systems, which stay on high alert and go on to attack healthy cells. But much of how the disease operates and compounds with other conditions is a mystery.

“With a novel virus or a novel illness, the research will always move slower than people need it to…But in the last six months, I’ve seen more papers getting closer to pragmatically helping people than we saw throughout the rest of the pandemic,” Sala said. “I think it’s finally hitting an inflection point where we’re going to come up with strategies to heal people faster from these conditions.”

Dr. Jerry Krishnan leads the long COVID clinic at UI Health, which has been active for the past two years, at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC). Coming to a long COVID clinic over a primary care doctor can be worth it because it means getting in touch with long COVID experts familiar with how the condition varies, Krishnan said.

“Long COVID can affect any part of the body. It can start in the original problems or areas you had, so if you had COVID pneumonia, maybe it starts with the lung, but it can also affect the brain…It can create almost any symptom you can imagine,” Krishnan said. “One of the most challenging aspects of diagnosing long COVID is that it isn’t just a specific list of problems.”

Long COVID can be difficult to diagnose. No single test exists for it yet, although some are under development. Its symptoms can also sound like many other health conditions, or it can complicate pre-existing ones, like diabetes or high blood pressure. Sometimes, a person with long COVID may not even realize they have it or chalk it up to aging.

“The diagnosis depends on whether you and the doctor can tell you had an infection that sounds like it was COVID, and after that, something changed, and you don’t have any other easy explanation,” he said. “You may have had diabetes for a long time, and then you had COVID, and then you realize you’ve had more difficulty measuring or taking care of your diabetes…It gets more complicated if you have underlying health conditions.”

Marta Cerda heads ASI, a home care agency that supports patients who are disabled or chronically ill. She caught a severe case of COVID-19 in the fall of 2020. After the infection, she recovered but realized she hadn’t recovered her full taste and smell.

“There were certain things that I felt when I had COVID, like extreme fatigue, that crushing feeling, and certain other conditions,” she said. “I definitely had brain fog, and then, the weirdest thing was that I started to stutter sometimes. It happens rarely, [but it’s like] my thoughts are ahead of my ability to speak.”

Despite working in healthcare for decades, she still had trouble connecting the dots between her COVID-19 infection and her lingering symptoms. But her questions led her to join the RECOVER study, an observational study of long COVID patients through the federal government’s National Institutes of Health. Krishnan directs one of the clinical sites for the RECOVER (Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery) Initiative, which he said has enrolled 15,000 adults, including nearly 1,000 in Illinois, to understand how long COVID impacts people and ultimately launch clinical trials to treat it.

Joining the RECOVER study helped Cerda understand where some of her unexplained symptoms were coming from. Now, she worries about the people in her communities who may have gotten long COVID but don’t realize it. It motivated her to get involved with long COVID advocacy and community outreach. She mentioned that the more individuals understand the presence of the condition within themselves, their family, or friends, the easier it becomes for them to seek help.

“There are legitimate reasons to fear clinical trials in our communities,” she said.”A lot of it is about being in the community with people who understand the fears and can say, ‘Yes, I understand, you’re correct, it’s important to have those fears, but this study is going to make sure you get all the information about what’s happening, and you can back out of it anytime.’”

Last fall, Cerda testified with Krishnan before the Illinois Senate Public Health Committee about long COVID. They both work with Illinois Unidos, a coalition of Latinx healthcare providers, policy advocates, and community organizations advocating for equitable COVID-19 recovery and response.

The pandemic has also impacted communities of color differently, as long-documented health disparities worsened its impact. Black and Hispanic adults were disproportionately represented among severe COVID cases. They were also more likely to report COVID-19 symptoms lasting three months or longer, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey.

“We want people to understand that the health disparities of African Americans, Latinos, and Asians caused us [to be] highly susceptible to long COVID. We got hit by COVID-19 the hardest because of those health disparities and because our immune systems were down,” Cerda said. “Once you got hit, in large numbers, we developed an exacerbation of all those issues within long COVID.”

In July 2021, long COVID became a recognized condition that could result in a disability—giving patients the same anti-discrimination protections or accommodations as any person with a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act. But more needs to be done, said Cerda. For example, long COVID patients are typically younger than the patients served by her home care agency, making them ineligible for this type of support.

UI Health is currently launching clinical trials examining brain fog, dizziness, sleep disorders, and post-exertional malaise among long COVID patients with partners at UChicago, Northwestern, RUSH University, and others. Researchers are also testing whether Paxlovid, a prescription treatment for acute COVID, can treat people with long COVID.

Krishnan said the state should create a dashboard to track the number of long COVID cases in Illinois. This would allow people to identify areas where long COVID is more prevalent and which neighborhoods or vulnerable populations need the most support. They’re also pushing for the state to disaggregate COVID data collection by different subgroups, like age, gender, race, and ethnicity, so researchers can better determine where critical resources should go.

“There is no single place where you can see which neighborhoods long COVID is more common than others,” he said. “That’s something we should ask our government officials to create,” he said. “At least those individuals now, we can look at them more carefully to bring the resources we have for those suffering the most.”

The best way to prevent long COVID is to avoid catching it in the first place. COVID prevention can include masking in public spaces, regular testing, or using air purifiers to remove COVID-19 particles indoors so people can prevent its spread and the complications it might bring.

Vaccination against COVID-19 also prevents infection, and many studies have also found that it significantly lowers the risk of developing long COVID after infection. But only 15 percent of Chicagoans are up to date with their vaccinations as of March.

While working with ASI to increase vaccination rates, Cerda has felt that people no longer want to hear about COVID-19. “Now, what I say is, ‘COVID did not leave me,’” she said.

“We have to think about it because people are dying or going to be dying from long COVID,” she added. “A whole group of people are now unemployed because they’re unable to work…This is impacting the country whether or not people want to talk about it or not.”

Reema Saleh is a writer, journalist, and multimedia producer. She last wrote about labor organizing at the Chicago Transit Authority.