Eric Basir started working at the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) five years ago. When he was younger, he wanted to become a rail operator, and he came in through an entry-level position. He loved interacting with riders and coworkers while he worked his way to becoming a rail operator and, eventually, a train mechanic. But now, he sees his time at the CTA differently: as a series of jobs full of burnout, hazardous conditions, and mismanagement.

“The CTA has been saving money hand over fist, cutting back on labor, quadrupling productivity.…It’s a superhuman ability of these train operators, what they’re doing now,” Basir said. “I always wanted to be a motorman ever since I was little. But I grew up when there were conductors [and] two-person crews. They’re undergoing so much mental [and] physical trauma. They say this is the most hated job—train operators. And it’s highly exploitative.”

Basir first came to the CTA as a customer service assistant before becoming a flagger working alongside rail operators to signal the way for passing trains. After five years, he now works as a mechanic, fixing trains. He also serves as a union steward with Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local 308, the union representing rail operators and other CTA workers. (Bus drivers have a separate local number, 241.) As a union steward, he volunteers to assist other workers with any questions or problems with CTA, advocates on their behalf, and served as a delegate to the larger Amalgamated Transit Union last year.

In 2019, he and other CTA workers formed the Chicago Transit Justice Coalition to empower fellow workers and hold union leadership accountable. Basir says the group was initially developed to empower part-time workers in Local 308, who had to pay full dues to the union despite not receiving full employment benefits.

“The inequities and the low wages are just too much for our part-time workers. So it started because we were promoting a revision to the bylaws of our ATU Local 308 to establish a fifty percent [due] for all part-time work,” Basir said.

The coalition emerged that December as it began drawing attention to labor grievances and calling for massive reforms to the way CTA runs. They began uniting with bus drivers in Local 241. The Justice Coalition is not a union or an officially recognized representative body. While Basir is a union steward with Local 308, he and the Justice Coalition do not represent the union’s positions. The group does not hold strikes, relying on off-the-clock protests or social media to get their message out.

With the onset of the pandemic, their organizing expanded to address more issues, including worker safety and hazard pay.

“As the first wave hit, we organized meetings among bus and rail workers to establish a campaign to fight for hazard pay,” Basir said. “No punishment, no discipline, paid time off for all the workers who were getting sick and establishing what we call mass virtual membership meetings so that we could plan actions and force the CTA, the state, and federal government to ensure our safety and our job security.”

COVID-19 brought on new challenges for the CTA, which is currently dealing with one of its greatest employee shortages in recent history. Like other transit systems across the country, the pandemic sparked a transit workforce shortage that Chicago is still experiencing. Overtime has become much more common. Last year, a WTTW analysis found that nearly fourteen percent of workers were working an average of fifty hours or more a week and that some employees were working over eighty hours a week.

“People are quitting, people are resigning, people are retiring early,” said one CTA worker who spoke anonymously for fear of retaliation. The worker said some employees are retiring early to collect disability benefits instead of staying until retirement age and a higher pension value. “People are running for the hills.”

Public transit has changed tremendously since the pandemic, and lagging service has become commonplace. Following the CTA’s optimization of services, Chicagoans have seen a more than twenty percent cut on rail and a thirteen percent cut on bus service compared to 2020, the norm according to the transit activist group Commuters Take Action. Organizer Brandon McFadden, who independently analyzes system-wide data, found there is still slight unreliability in the service that the CTA has been able to deliver.

“Until the CTA improves working conditions for CTA employees, we’re not going to make any progress on hiring. It’s just that simple,” said McFadden at a rider’s protest last week calling for CTA President Dorval Carter’s removal. “They still rely on operators to build extra time and overwork their schedules beyond what a normal forty-hour work week looks like. You can’t rely on people to bend over every single week and overwork themselves just to run the minimum schedule that you think you can.”

Bus operator Aundra Thompson has worked at the CTA for over thirty years. He organizes with the Justice Coalition partly because the runs that the CTA schedules have become less realistic over time.

“It’s a manpower problem because people are not attracted to want to work here,” Thompson said. He believes that is one of the major reasons behind service unreliability—what some commuters have called “ghost buses”—a problem that has persisted even after the CTA cut scheduled services to try to address it.

Since launching its Meeting the Moment Plan last year, the CTA has created a public data portal to monitor its progress toward delivering reliable service, enhancing safety and security, and investing in employees.

“We’ve made noticeable improvements to virtually every aspect of our riders’ experience,” Carter said this August in a statement. “And while we are encouraged by the progress we’ve seen since implementing a variety of new initiatives, we know there’s still more work to be done.”

The CTA has characterized its closures of service gaps as “schedule optimization,” but transit advocacy groups like Commuters Take Action and the Active Transportation Alliance have criticized that as overworking employees. Making those runs with ongoing staff shortages has come with a personal cost for some workers.

“They don’t have the manpower that they need to provide all of those time slots for those buses that you see on the schedule.…Those runs can’t go out without a driver,” Thompson added. “It’s just scattered through the city, of runs that’s not supposed to be out there but was already paid for to be out there by the public.”

With fewer bus operators clocking in compared to before the pandemic, routes are scheduled to be faster, leaving less room for breaks or recovery time at the end of them.

“At the end of the line, they have what’s called recovery time. That’s the amount of time that the bus sits before it heads back out. Over the years, CTA has been dwindling that recovery time. They even got some routes in our garage where you only get three minutes,” said one worker who requested anonymity. “And then when you get to the end of the line, you only got three minutes to use the bathroom, stretch your legs. You need more than three minutes. And CTA has done that with a lot of the routes that we have. They have tried to squeeze more work out of the worker and eliminate more of your break time.”

In an email, CTA spokesperson Kathleen Woodruff wrote, “There were a few routes that saw average layover times decrease as part of recent schedule optimization efforts. However, overall and systemwide, the average layover time increased.” According to documents obtained by the Chicago Reader , current recovery periods last around five or six minutes or occasionally less when they used to last fifteen to twenty.

Thompson said this has meant shortening the time CTA workers have between shifts and adding more stress to the job.

“Sometimes the operators are forced to mess the schedule up because they need more than four minutes. With CTA, it used to be twenty to thirty minutes at the end of the line,” Thompson said. “What CTA said is, instead of getting four trips out of the worker, we’re going to get five or six trips out of them and give him the same amount of time.”

The pandemic catalyzed worker departures, and its aftereffects on the transit workforce have lingered. The CTA has cited an aging workforce and nationwide transit operator shortage as contributing to a mass workforce decline. Last year, a survey by the American Public Transportation Association found that ninety-six percent of transit agencies were having workforce challenges, and eighty-four percent reported that their staffing shortages were impacting service.

“During the pandemic, the CTA workforce was revealed to have had many preexisting conditions or underlying health effects that would have made them susceptible to contracting COVID. If they did, they would have had a very difficult time getting through it,” said P.S. Sriraj, the director of UIC’s Urban Transportation Center. But in addition to the hits the workforce took from the pandemic, Sriraj said the decline “has been years in the making” because of growing opportunities for operators to find better work environments and higher pay elsewhere.

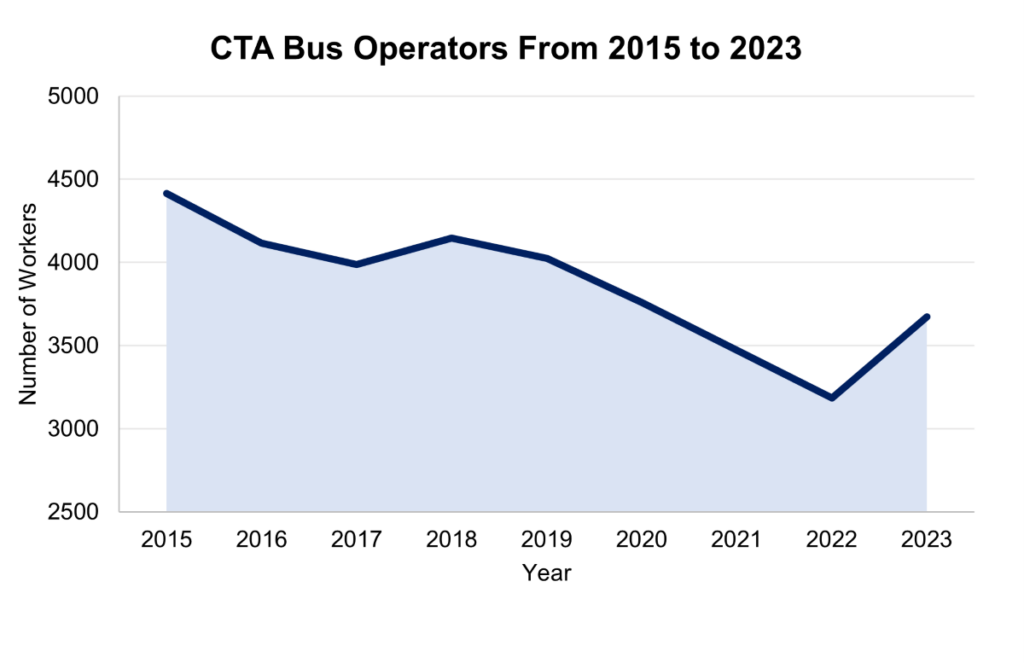

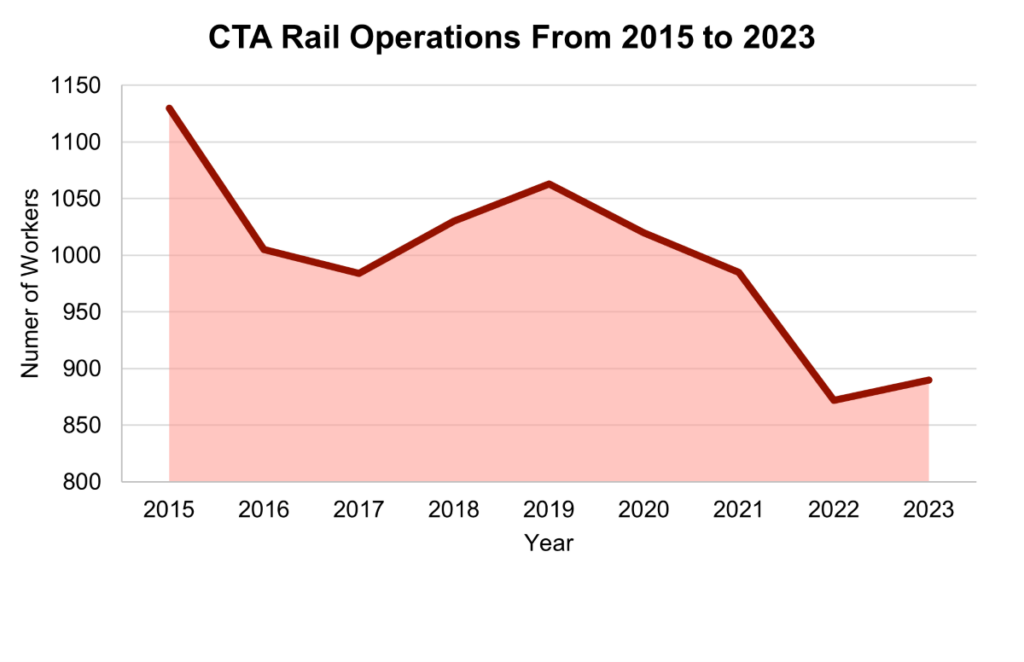

While the CTA has made progress toward filling the nearly 1,000 vacancies Carter said the pandemic left in its wake, workforce has a long way to go before it has fully rebounded. An analysis by the Weekly of publicly available data from the Regional Transportation Authority, the Illinois agency overseeing CTA, Metra, and Pace, shows that as of August the number of CTA bus operators and rail operators (including operators and flaggers) were still down by fifteen percent and sixteen percent, respectively, compared to 2019.

“It becomes a very vicious cycle. If you do not have enough operators, then you’re unable to provide service…but you’re still obligated to provide the same frequency of service in order to attract the riders back,” Sriraj said. “If you don’t have the operators, then you put up a schedule, and it doesn’t show up in reality. Then people start worrying about the reliability of the service.”

Workers with the Justice Coalition argue the staffing shortage is to the detriment of workers themselves, who bear the brunt of the losses. But they also say poor workforce conditions predate the pandemic.

Last December, the Justice Coalition held an off-the-clock demonstration focused on Second Chance Program participants. The CTA’s Second Chance Program reserves job opportunities for prospective employees with criminal records or other barriers to entering the workforce. That day, the Chicago Transit Justice Coalition protested CTA management for poor working conditions and a lack of full benefits for program participants.

“It’s a second-class program. They got these poor people in our rail yards, walking around cleaning trains out in the railyard,” Basir said.

The CTA says that since 2011, the Second Chance Program has hired over 2,000 people previously involved with the justice system, 550 into permanent positions. It opens doors into the agency by partnering with reentry programs by many of Chicago’s social service organizations, helping people overcome employment barriers, like past involvement with the justice system, surviving abuse or domestic violence, or housing insecurities. It lasts up to a year and offers full-time work and training to fully enter the workforce. But some workers argue that the program is letting its participants down on pay and benefits.

“The CTA is in a position to create better pathways, jobs with better benefits. But for whatever reason or another, they still have these minimum-wage jobs….These people that come in the Second Chance Program make $15.40 [now $15.80], are cleaning the buses, and they clean the buses overnight. They don’t clean the buses during the day,” said a CTA worker who preferred to remain anonymous. “And they’re dealing with chemicals all day long. They get no benefits. No health care, no dental, no vision.”

With no guarantee of future work, some graduates of the program were left disappointed. After completing the Second Chance Program and being unable to find a permanent job at the CTA, one employee told the Reader, “You know what happens when you graduate from the Second Chance Program? You graduate to the unemployment line.”

In her email, Woodruff wrote that the CTA doesn’t “have a mechanism to track graduates who find employment outside of CTA,” but that they have “heard from employees and social service organizations” that “many have gone on to work in the private sector and have been successful in other career paths.”

For Thompson, the Second Chance Program creates divisions among CTA workers, especially when Second Chance Program participants are doing work comparable to those making higher wages at the CTA.

“All this is creating stress. All these tiers of workers are doing the same job,” Thompson said. “How do you think they feel standing next to another guy making $40 an hour, and they’re not making enough? They’re pitting workers against each other. It’s creating more stress among all workers.”

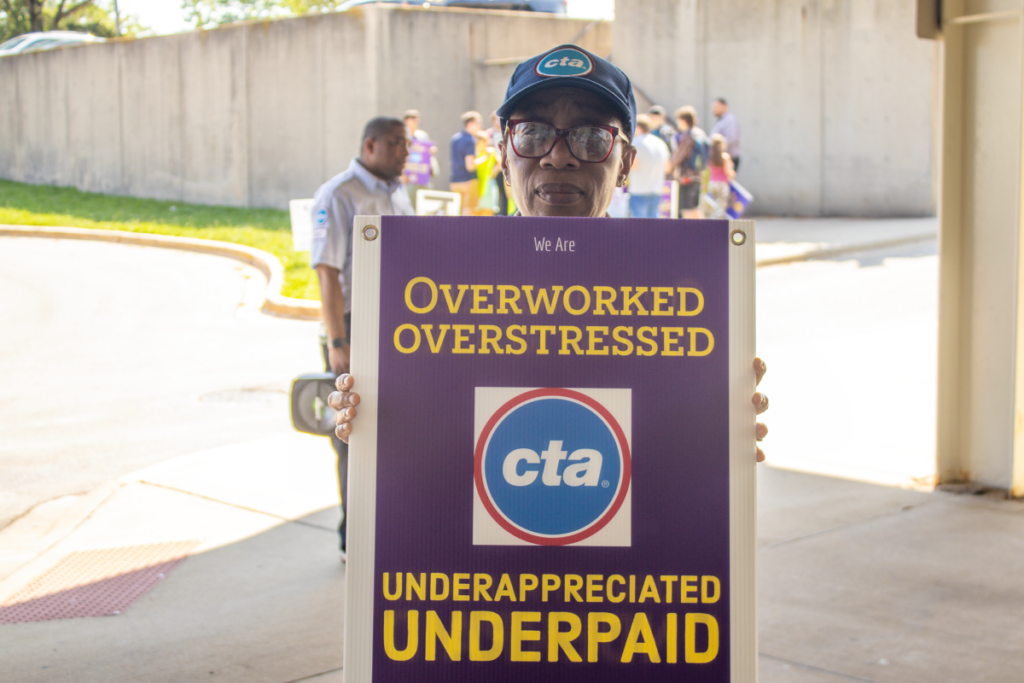

In February, members of Chicago Transit Justice protested outside the Jefferson Park Transit Center, calling for better working conditions and accountable leadership. On July 14, the Chicago Transit Justice Coalition protested outside the CTA Blue Line’s Forest Park terminal. Joined by Commuters Take Action, Chicago Democratic Socialists of America, and other organizations, workers shared stories of alleged wrongful termination and called attention to the CTA contract, which is expiring at the end of the year.

Though it took place years before she began working at the CTA, Kathryn Strzelecki, a switcher for thirty-four years, still remembers Chicago’s last transit strike in 1979. Local 241 and Local 308 held a three-day strike as both bus and rail operators walked off the job to demand a higher cost-of-living adjustment from the city.

Strzelecki, who retired in 2018 and spends her free time organizing with the Transit Justice Coalition, says conditions have gotten bad in recent years. “We are working under stress and wages that don’t keep up with the cost of living. It used to be a good blue-collar job, where you could buy a home, you could send your kids to school, you could take vacations. But it’s not that kind of job anymore,” she said. “It’s not an entryway into the middle class for blue-collar workers.”

Five years after the 1979 strike, Illinois enacted the Illinois Public Labor Relations Act, which prevents public safety workers like police officers, firefighters, and paramedics from striking. While other public employees can strike under certain conditions, current and past collective bargaining agreements between the CTA and Local 241 and Local 308 outlaw striking in favor of interest arbitration.

Since Local 241 represents bus operators separately from other workers in Local 308, negotiations happen separately, even though their interests often align. CTA employees can often work months or even years without a contract while it is being negotiated, and receive concessions for past work retroactively.

From 2016 to 2018, CTA workers worked without a contract. In the middle of those two years of negotiations, Local 308 voted to authorize a strike, while the CTA maintained that the union did not have the right to strike in the first place. The current contract covers 2020 to the year’s end but was approved in 2022. For Strzelecki, this arbitration process has lost Locals 241 and 308 much of their bargaining power.

“Even when I started in 1984, people used to say, ‘It’s the union and the CTA against the membership.’ When you look at the contract, the CTA has always won,” Strzelecki said. “The union leadership, anywhere, not just at the ATU—you can’t talk your way into a good contract. If you’re not threatening to strike or actually going on strike, the bosses are gonna do what they want to do.”

This summer, in response to Mayor Brandon Johnson’s 2023 transition report, the Chicago Transit Justice Coalition issued a list of goals for reforming the CTA, including eliminating part-time jobs, expanding two-person crews, and investing in workers and facilities.

Since February 2022, bus operators have been recruited directly into full-time service. Rail operators aren’t. Before becoming a rail operator, entry-level employees must work as flaggers—a full time temporary job, which CTA says can take six months to a year to be promoted to a permanent position in the rail division. According to some employees, part-time employees working in train stations, cleaning, or customer service are stuck in this cycle.

Woodruff wrote that it’s the collective bargaining agreement “between the CTA and its unions—not a CTA policy—that determines the pick process, as well as the creation of full- and part-time positions.”

Thompson believes that this cycle of part-time work is making life worse for workers, especially for the CTA’s majority-Black workforce, which comprised nearly seventy percent of all CTA employees in 2021.

“How could anybody get out of poverty working for CTA?” he said. “They come to work because they think it’s a good job and they really needed a job, but that’s not helping them get out of poverty.”

Another proposal the Justice Coalition is pushing forward is a call for two-person crews—a shift from a sole driver operating the train and handling issues in the cars.

“You cannot fulfill your duties as a train operator. You can’t by yourself. It’s impossible to maintain on-time performance,” Basir said. “You’re putting out fires. You’re dealing with customers that have lost and found items, you need directions, fights, people overdosing, people having heart attacks, people jumping off the track. You got workers doing work on the side of the track.”

With two-person crews, a second conductor opens doors, checks for safety issues and handles anything that comes up along the way. Now, a conductor does both jobs. Two-person crews was a practice that CTA ended over two decades ago, but bringing back a second conductor as a new set of eyes and ears is something that Basir believes is the key to keeping rail conductors focused on driving and passengers safe from harm.

“It used to be two people operating the train.…It’s too stressful for one person to operate an eight-car train and have to do everything, plus drive the train,” Thompson said.

Some critics argue that two-person crews do not increase safety, and could exacerbate existing workforce shortages. But the Justice Coalition’s members say that two-person crews would decrease worker fatigue and enable conductors to watch for safety issues or passenger disruptions in the cars.

Thompson also drew attention to other issues at the CTA, particularly the lack of brick-and-mortar bathrooms for bus operators.

“Who wants to go on a porta potty at nighttime and it’s zero degrees outside? They should have brick-and-mortar bathrooms with running water and heat to be safe, with locks on the door.”

Woodruff wrote that the “construction of permanent restroom facilities along bus routes is logistically and financially challenging” and would allow less flexibility in the event of route changes. “The CTA has also secured access to nearly one hundred other permanent restrooms at retail stores, commercial and public buildings, and other locations along bus routes and rail lines.”

Alongside these reforms, the Chicago Transit Justice Coalition is pushing for an overall change in leadership at the CTA, including replacing the CTA’s current board of directors and replacing it with an elected board composed of riders and workers. For the Justice Coalition, solutions to the CTA’s workforce problems can only come with putting CTA workers first.

“I think what people need to know is that people work long hours on the CTA, and they don’t get the proper sleep. It’s physically taxing, and it’s mentally and physically [and] very stressful,” Strzelecki said. “But I think everybody is facing a lot of the same conditions.”

Reema Saleh is an writer, journalist, and digital media producer. She last wrote about South Shore’s fight for affordable housing protections.

Why isn’t the subject of the employees who were terminated for not taking the covid vaccine? The dismissals openly and clearly violated the terms ratified in the contact with CTA. When is that going to talked about and finally publicly acknowledged?

They were totally violated. The ATU presidents just gave the decision to an arbitrator—who sided with the CTA. Never even asked us what we wanted to do to fight. Other unions got weekly testing.