For José Orduña, immigration policy registers as surreal. On account of legal fictions—paperwork, borders, citizenship—human beings are taken at gunpoint, carted about in caged backseats, and shuffled through courtrooms in shackles. When you consider just how the American border is policed, is there any other way to rationalize it?

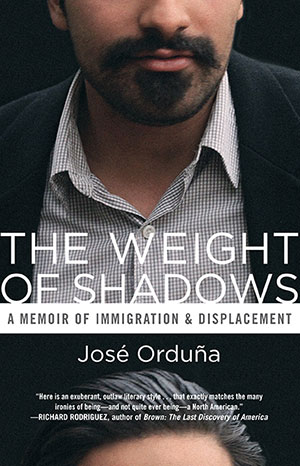

In The Weight of Shadows, his first book, Orduña recounts a lifetime as the “other,” from his childhood as resident alien to his naturalization as an American citizen in 2011. When distilled to a synopsis, it reads like an underdog story. But Orduña, an adjunct at the University of Iowa who was born in Veracruz but raised in Bucktown, renders immigration policy with both the panache of a writer and the dread of someone who’s lived through it firsthand. It’s hard to say whether The Weight of Shadows is more disturbing in the anecdotal or the statistical, but it lacks for neither.

Over the course of the book’s two-hundred-odd pages, Orduña narrates a near-endless list of human miseries: broken femurs neglected by Border Patrol officers, gun-touting vigilante bands prowling the desert, children left unattended by parents detained in traffic stops. But he delivers mind-numbing statistics with similar ease: for instance, that even the Border Patrol’s own low estimates suggest that “nearly as many people have died trying to cross the southern border into the United States as there were U.S. soldiers killed in Iraq.”

Although much of Shadows revolves around the long road toward citizenship, the last quarter of the book focuses primarily on Orduña’s work with No More Deaths, a humanitarian group which works to save the lives of migrants crossing the border by providing water and medical attention. With his own citizenship recently secured, Orduña and a team of volunteers rove the desert—where they are frequently confronted and surrounded by armed Border Control officials.

Orduña’s advocacy with No More Deaths eventually takes him from the heat of the desert to air-conditioned federal buildings—but American rule of law seems no more just on the other side of the borderlands. When he observes the en masse trial of detainees in an Arizona courtroom, he remarks that it has the anachronistic air of a historical reenactment. How else does one make sense of the denial of immigrants searching for a better life, particularly when one’s own nation has been “deeply involved in creating the conditions being fled?”

For Orduña, it is not only the border, but the courtroom, “where justice reaches its vanishing point, sheds its veneer, and reveals itself fully as punishment.”

Just as Orduña’s existence in America is divided between two distinct identities, Shadows is a hybrid work: at once memoir and polemic. At times, it’s deeply personal and confessional—and yet, it’s interspersed with enough contextual information to warrant a fourteen-page bibliography. But this duality speaks less to Orduña’s intimate knowledge of American immigration policy than to the conflict at the heart of the book: the intersection between the human and the institution, and the violence that results.

And so, just as the individual narratives of immigration dovetail with the structural, Orduña notes the ways in which his own life intersects with the broader history of immigration in America: “the eternal return of the circumstances into which [he] was born,” a sort of dual consciousness. He writes about singing along to “La Guacamaya” as a child in Chicago, but also recalls being handed his first identification card and being lectured by his mother about violence inflicted by el estado in Tlatelolco.

Indeed, Orduña’s relationship with the state is convoluted, but he does eventually secure his American citizenship. After living in Chicago for twenty years, he writes, it feels significant to be naturalized “under the sign of Obama, the record-breaking deporter in chief, with Hoover, the president during the beginning of the Mexican Repatriation, in retrograde.”

Near the end of Shadows, Orduña discusses Fenómeno, a work by the Mexican artist Remedios Varo. In the painting, a shadow—blank, dark, featureless—stands in a courtyard, with the image of a man cast across the ground as if it were the shadow. For Orduña, the surrealism of the painting reflects the surrealism inherent to the immigrant experience: it “serves as a kind of spirit photograph, a depiction of the zeitgeist.”

And what does that photograph depict? Someone “made invisible in plain sight—that is, invisible to the civic body in which one continues to exist[.] Someone turned into a walking shadow, with the dimensionality of a person but without the possibility of recognition.”