On April 29, multimedia artist Luke Fowler’s exhibit opened at the Neubauer Collegium, the University of Chicago’s center for research in the humanities. The gallery is small—only three rooms—but somehow feels expansive with its sparse openness. The floors are sleek and smooth, but one feels hesitant to make too much noise on them in an environment that so clearly reveres and cherishes art.

The minimalism of the space complements the nature of Fowler’s work. The small room where the photographs hang, with its contemplative setting, could easily be one of Fowler’s own photographs. Within the exhibit itself, calmness emanates from both the quiet admiration of Fowler’s art and the art’s simplicity. Through symmetry and soft colors, Fowler’s work evokes a sense of meditative tranquility, of using one’s home as a resting place from all the turmoil in the world.

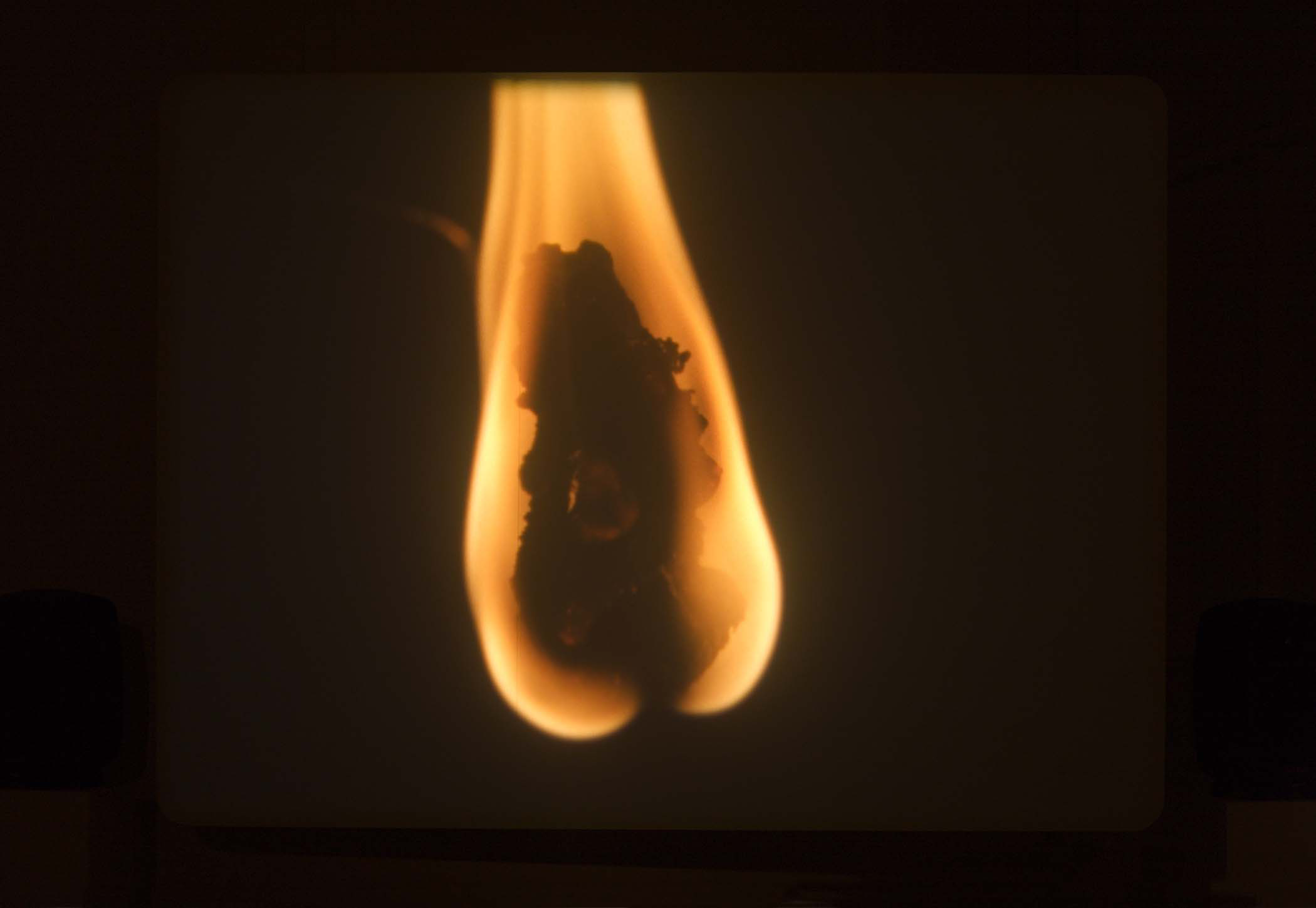

Based in Glasgow, Scotland, Fowler engages with several forms: visual art, music, and film. This multiplicity of mediums coalesces in one of the films on exhibit, For Christian, cinematically representing the New York School composer Christian Wolff. Shot in 16mm, the short film has a grainy, vérité quality reminiscent of 1970s New Hollywood or British New Wave cinema. Wolff’s music lilts in the background over a series of footage of nature scenes and animals; the editing is jerky, matching the staccato of the score. Fowler’s films, more so than the other art forms he explores, tend to focus on trailblazing intellectuals and creative types, oftentimes avant-garde in their cultural production. He gains insight into their creative processes, the impetus for their pieces of art. In the case of Wolff, though, he lets the music do most of the talking.

For Christian is accompanied by Fowler’s rarely seen Tenement Films, which follows four people—Anna, Helen, David, and Lester—dwelling in the same Glasgow tenement. Tenement Films does not employ any artificial lighting, giving the film a murky, textured quality. Also shot on 16mm, the project reflects Fowler’s usual fascinations with the intimacies of people and their homes. Fowler received a degree in printmaking; his background can be sensed through his specific attention to detail. Despite the film’s prosaic nature, Fowler’s use of close-up and the film quality give it a lush feeling. We glimpse the characters’ majestic view of Glasgow, beads of water on a window, the shadows of blossoms through an opaque curtain. For a moment, each of them looks like still photography. When the commonplace details of life are gazed at so deeply, they become something entirely new to the eye.

Fowler investigates similar themes in the color photography on display. One set of photographs was shot in the home of Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri, featuring crisp images of his meticulously organized books and magazines. There is a comforting sense of domesticity, the intertwining of work and living space. Fowler captures how artists reflect their aesthetic sensibilities in their domiciles: for them, there is no line between life and work. In honing in on the minutiae of daily life, a facet usually overlooked by the general public, Fowler both makes artists real to us and illuminates them. They are normal humans who go about their lives in domestic areas, but they also bring an artist’s eye to even the most mundane aspects of their lives (exemplified by the precise color scheme of the book spines in Ghirri’s library).

The other series of photographs was taken in the studio for electronic music at Cologne’s Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR), or West German Radio. In contrast to Ghirri’s organized, hazy-colored space, the studio is cramped with machinery and wires. The objects captured are in the midst of carrying out their obscure functions, lit up and blinking. Fowler is able to engage with varying kinds of milieus while still drawing from them the same type of effect—hushed, pensive. The bodies of the homes and working environments seem to speak more than the actual bodies that inhabit them: the latter are, in fact, oftentimes absent from the scene. Perhaps this is what he is trying to say: what is not there can be felt all around us, much in the way the gallery, and all of its unadorned space, interacts with the art.