We believe that if you have a whole system problem, only a whole system solution can transform it,” announced Naomi Davis, founder and president of the grassroots community development organization Blacks in Green, to an auditorium full of Chicago Humanities Festival patrons on Sunday afternoon.

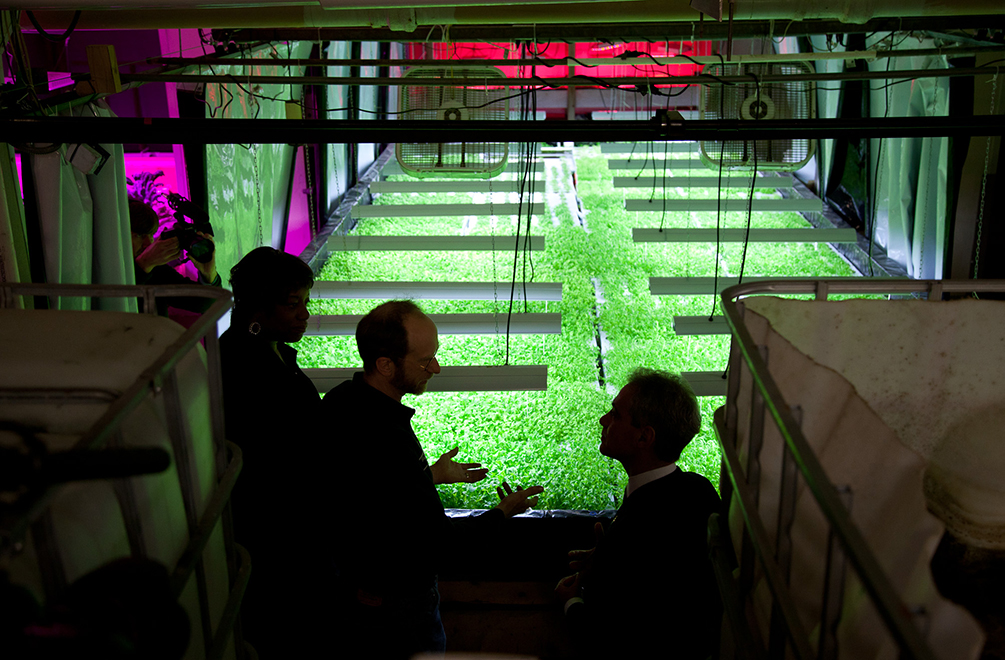

Davis’s co-panelists and fellow South Side community leaders, John Edel of The Plant and Harry Rhodes of Growing Home, presented a similarly passionate case about the “Farm in the City,” as the event was titled. They envision urban agriculture as a remedy not only for what Chicagoans eat, but also for what goes on on our streets.

Rhodes characterized Growing Home’s urban agriculture work as at the juncture between social enterprise, transitional employment, and community development. Between its four local farms, the organization generates 13,000 pounds of organic produce a year. But Rhodes believes an integral result of their urban farming operations is the job training they offer formerly incarcerated or homeless interns, ninety-five percent of whom never return to the prison system, as compared to the fifty percent average for released convicts in Illinois. Growing Home’s gardens and Englewood farmstand serve as safe havens in one of the city’s most violent communities. “When you bring people together in a garden, bad things don’t happen,” Rhodes assured the crowd.

When asked by moderator Lee Bey whether it was a coincidence that they all worked on the South Side, the three panelists quickly expressed a consensus answer: “No.” While the models are meant to be replicable in many Chicago communities, the legacy of deindustrialization and what Davis termed the “foreclosure tsunami” on the South Side have left acres of vacant land and a desire for community safe havens that make it a natural place to start. Davis explained her motivation for working in urban farming as a desire to spearhead holistic community development. There is, she commented, a “high cost of doing nothing in neighborhoods like mine, in West Woodlawn, where people die on the street, as surreal as that may seem,” she commented.

This starting point for the urban farms—abandoned lots, unsafe neighborhoods, and resource scarcity—was geographically far removed from Sunday’s discussion, in the high-tech auditorium of the Lincoln Park charter school that hosted the event. While the setting signaled the newfound trendiness of urban farming on the municipal level, the audience was keen to interrogate the larger institutional roadblocks that still limit this all-encompassing solution. One astute and wary audience member asked Davis whether the UofC is “just keeping quiet about this or are they hatching anything behind closed doors?”

In response she described the vacant lots in West Woodlawn that are not yet in community land trusts as “perched precariously within the talons of the University, which quite clearly has a plan for developing” the neighborhood. “The University of Chicago is six of one and half a dozen of the other,” she said, as Blacks in Green has also received support from the UofC and has many university allies in pushing forward their initiatives that don’t concern real estate development, such as backyard gardens.

Edel eloquently characterized the city’s equally ambivalent initial attitude towards urban agriculture: “We were being told ‘No. Absolutely not’…in writing. There were several signatures on that. But being told privately, ‘Do it, do it. We want you to do it.’ Well we did it.” And, seemingly due to all this grassroots work, zoning laws have changed. The mayor’s office now encourages urban agriculture—at least in writing.