Do black people read?” It’s 1981 and Turtel Onli is biting his tongue in a New York City office. “When black people read science fiction, do they understand it?” Onli is pitching a revolutionary idea for the industry, but the vice president of a big-name comic book company is confused: What purpose do African Americans have in comic books? No one could possibly want to read about a black Superman. So Onli leaves, empty-handed and determined. But he didn’t want just a job. He wanted an entire genre. So he didn’t get mad. He got busy.

As Peter Tosh once sang, “We’re sick and tired of your -ism and schism game.” Onli has dedicated his life to preventing “-ism schisms” from defining who he is. His projects have included coining the term “Rhythmism” to define his stylizations; founding the Black Arts Guild; teaching art classes in Chicago Public Schools; establishing art therapy programs at mental health centers; working as a major-market illustrator for magazines such as Playboy and Ebony; and teaching at Harold Washington College. It’s hard to imagine a New York executive disputing the passion pouring out of this man’s mind because of the color of his skin.

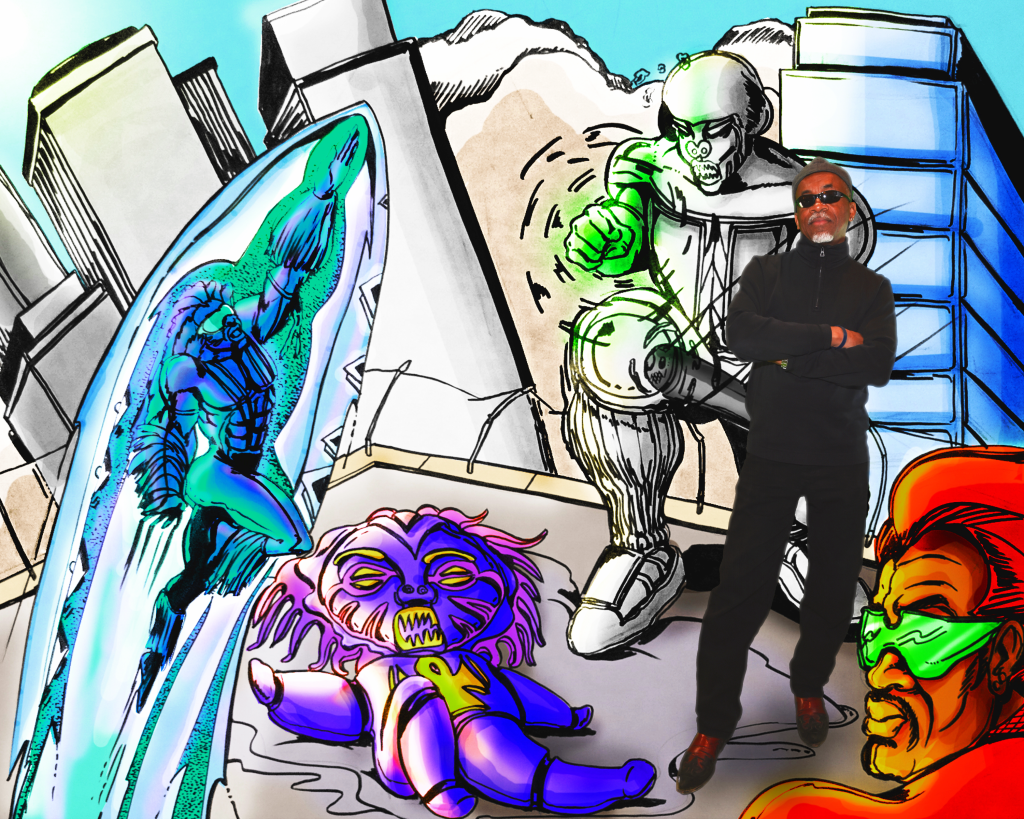

With the publication of his first comic, NOG: The Protector of the Pyramides, which focused on his character Nubian of Greatness, Onli pioneered the innovative Black Age of Comic Books. He describes the genre as exploring “material that comes from a black African independent or urban experience.” In 1993, Onli also created the first Black Age of Comics convention, which took place at the South Side Community Art Center. The back page of his comic Malcom-10 reads, “In this time of drift, where lack of integrity, rudeness, discourtesy, education ‘is a white thang,’ and ‘kicking back with a 40,’ are the definitions of Blackness, in this time where Super rude is cool, we are in dire need of black super heroes, to inspire and guide our youth.”

The Weekly sat down with Onli in his Bridgeport studio to discuss how he became a self-identified black-hippie, what’s wrong with the comic book industry, and how he launched the Black Age. An edited and condensed version of this conversation follows.

I grew up in Hyde Park before the Civil Rights Act. My grandfather, who is black, owned seven buildings, including a huge building in Hyde Park. There was an orphanage nearby that had white students in it. And Donny and Tommy were my friends. When we were about nine, they explained to me they had potato soup for Thanksgiving. I sneak them food. There was a wall around the orphanage, we used to jump up and down to play and talk to each other. That’s how we played! A lot of my playmates as a little boy were black, white, African, Japanese, Polish immigrants, Jewish immigrants.

Because of what I grew up with as a kid, let’s just say my peers, I was a little different than them. I got a job working downtown in the Prudential building. In 1968, when Martin Luther King got murdered, the city’s on lockdown because there’s riots. We couldn’t go home because the city was under martial law. I’m up there seeing what they’re not televising. People getting murdered. People getting their ass whooped. Police beating the hell out of people. I’m sixteen. So I had a little bit of a convergence. I decide America’s falling apart and it’s all going to dissipate into a chaotic revolution. I think in some kind of way being an artist can help that not happen. Magical thinking. Art to the rescue. So I want to start an artist’s guild.

I form an artist’s guild coming out of high school. The idea of the guild was to, one, help talented visual artists to make the transition from art student to creative professional. And internally, we were going to change the pickaninny into a positive icon, like the leprechaun. If the leprechaun could be drunk and claim he has a pot of gold and everybody think it’s cute and wonderful, why can’t the pickaninny chill out and smoke a joint and eat some watermelon and that be cool too, right?

My way of responding to a problem or an opposition is not to get mad but to get busy. I was at the Louvre, and I saw this exhibit. They had engravings from Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign and they had a garrison set up, and the sand of the Sphinx was up to its neck. So the guns were up, and they were blasting the face. Napoleon was offended that anyone could admit that black Africans had a civilization of that level at any time in history. So he, art historians, archaeologists, they don’t show you the black folks. We don’t want to tell THE story. And I’m sitting there in the Louvre and I’m like, mkay. So that’s when Nubian of Greatness was created.

The power of comic books is that it forces you to digest words and pictures. It is the process of pictures and words that has made us human. That has given us neurologically a big brain. The more art you did, the bigger your brain got. And the more your audience checked out your art, the bigger their brain got. So I looked at the comic book industry and I ran into things. Remember I said I don’t just get mad, I get busy? So I got real busy. I’m like, I’m gonna launch a genre.

I launched a movement. I gave it its name, and they had me come out to Temple University and gave me a lifetime achievement award. On the award, it said Father of the Black Age of Comics, which I’m still getting used to saying in a sentence. It’s one of those humbling honors that is taking a while to digest.

So a lot of things happen and I publish my first book, NOG: The Protector of the Pyramides. I wanted my copyright; I want to negotiate this sucker. What you’re missing is that back then, I was hard-core vegan. I used to wear sandals in the winter. I used to not use hot water unless I had an injury. I didn’t date meat-eaters—even if they were cute. I used to coat myself with olive oil mixed with special coconut oil resin. That ain’t really what they were expecting on the other side of the desk, least of all packaged as this.

We’ve come a long way. When we can’t say that, we miss everything. But there it goes. It’s so funny because when I conceived Black Age, one part of it was simple language: if you come from a black background that puts you in the Black Age. I couldn’t believe the pushback. In black circles. In black pan-African circles. In white circles. In Jewish circles. I was like, mkay, this is going to be a long-ass whooping, but I’m in it to take it.

It was new, and they could not conceive of it. No one had put those two words together. I had people from all those points of view tell me those words don’t go together. Because there is something empowering when you call it a Black Age. And how dare you, who gives you the right to call it that? I’m not going to trademark it. You can’t trademark a movement. So I’m just going to throw it out there. I’m just gonna throw it out there, because it’s not a movement if I own it. It’s a movement if you can participate and say, well, I want to do this with it. Well, honey, go for it, and let’s see what you do. That’s a movement.

I could tell the success of the Black Age of Comics, because the industry has responded with hiring more black people, more women, more Asians, with diversifying this product line. [But they’re far behind.] They’re very archaic, very unenlightened. And people haven’t challenged it, so I’ve been taking a hit. We’ve been growing. It’s been slow. It’s been hard. It’s not like food. Say you go down the street and you see a sign that says “Chinese food,” you don’t turn to your friend and say, “Oh we’re not from China, they must not want our business.” You don’t say, “Maybe they only want Chinese people there.” You say to each other, “Let’s check it out.” But when we call something black, because your mind is messed up, the first thing you say, you think it must only be for black people and they don’t want us there. Who did that to you? Because we didn’t. When we say black, we giving you an idea of what it is. So you can check it out. And not in intolerance, but in appreciation. So we don’t get this “do black people read?”

If I’m gonna take on a fight, let me take on a fight to grow fresh instead of rehabbing stale. I know what you’re doing. But more importantly, I know what I’m doing. And it’s changes like this that I let flow through me, and I keep pushing that ball uphill. Because people don’t like a pioneer. If we have any tradition in this country, it’s called growth and change. We’ve come a long way. When we can’t say that, we miss everything. We miss everything. But there it goes.

Alex Harrell is an amazing writer. I look forward to reading her articles with each publication

What a great article by Ms. Harrell

Loved Father of the Black Age! Great job Alex