“I feel like the best way to describe it would be nostalgic, but new-sounding at the same time. There are moments in some of the songs that may remind you of something you’ve felt, seen, or heard before. But the song as a whole feels like its own thing.”

Andrew Goes to Hell, a songwriter, producer and vocalist from the southwest suburbs of Chicago, is describing hyperpop—the term commentators have used to describe the new vanguard of electronic music taking shape across Chicago and around the world. According to Billy Bugara, co-founder of online label deadAir, it’s “just contemporary future pop… It’s taking pop music to levels it hasn’t been, as far as experimentation, creativity and embodying the modern sentiment in general.” But this can take a dizzyingly broad range of forms: as Chicago Reader writer Leor Galil puts it, hyperpop is “a frustratingly imprecise umbrella term that refers to a growing pool of stylistically disparate pop experimentalists.”

And if hyperpop’s sound is difficult to triangulate, then its origin is even harder to pin down. The mainstream stories that have popped up to explain this new genre typically attribute its founding to the Spotify playlist that coined the term in 2019, to the 2019 debut album from the band 100 gecs, or to the label and musical collective PC Music, which dates back to 2013. All of these groups share common sounds and production techniques, such as sped-up tempos, high-pitched vocals, blown-out synths, and other futuristic electronic flourishes—and much of it is popular in Chicago. But despite these connections to the city, one overlooked influence on—and predecessor to—today’s hyperpop music is Chicago bop, a type of rap music that was pioneered in the city in the early 2010’s by artists like Kemo, Stunt Taylor, and Sicko Mobb, and producers like DJ Nate, Mudd Gang, and the late LeekeLeek. Nine years ago, in a Pitchfork article on Chicago’s bop scene, writer Meaghan Garvey described the genre as “buoyant, upbeat and heavily reliant on autotune rap-singing.” Today, the description seems like it could double as an account of hyperpop.

“I imagine history will flatten what Chicago rap sounded like in the first half of the 2010s into top-to-bottom doom and gloom,” Garvey wrote in an email to the Weekly, “but that wasn’t really the case. In all the early tapes from guys like Keef and Durk, there’d be these moments of total exuberance, like ‘Save That Shit’ on Back from the Dead in 2012. That specific sound—which was sort of tinny and chintzy and to some people, probably really annoying—was popping up in tons of new Chicago songs I’d find while trawling Youtube, and I became a bit obsessed with organizing it into something coherent, because it was so awesome and because it fleshed out the narrative of what was happening in Chicago rap.”

If drill emerged as sort of a bastard offshoot of Atlanta-style trap, Garvey says, then bop picked up where the upbeat, chipper, sound of Atlanta artists like Soulja Boy and Travis Porter left off. “Basically, it was party music.”

The production on bop songs typically includes heavy bass, high-pitched synthesizers, and other electronic sounds that complement the autotune, as on DJ Nate’s “Gucci Goggles,” Ballout’s “Lean,” and Stunt Taylor’s “Fefe on the Block.” Hyperpop includes many of the same characteristics, especially the autotune and synthesizers, which are blown out to maximum effect on tracks like Nigo Chanel’s “Barbie.”

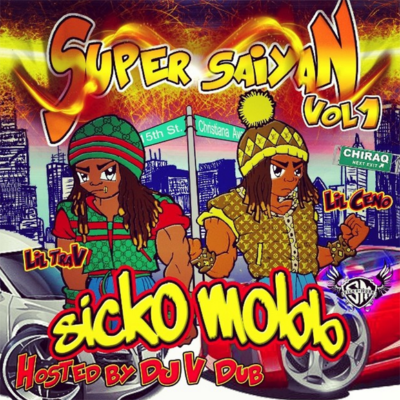

But as with many other genres which took root in Chicago—rock and roll, country, and house music, to name a few—the Black pioneers of bop are often overlooked in the mainstream media’s hyperpop conversation, in favor of discussion around white artists like 100 gecs or PC Music’s A.G. Cook. While Sicko Mobb did sign a record deal with Polo Grounds/RCA in early 2014, the deal did not live up to the group’s potential, and they haven’t released music as a group since 2016. This is despite the fact that Sicko Mobb did more to create the Chicago bop sound than any other artist—especially through their output in 2013 and 2014. As Garvey writes:

“To me, Sicko Mobb encapsulated everything I loved about the bop sound: it had these subconscious shiny pop impulses, but presented in this totally bizarro way that made it cool and interesting, with these giddy tempos and synth arpeggios and sugary melodies, on the more-is-more-is-more tip. I always thought of it like superflat art, i.e. the style of Takashi Murakami, bright and hyper-saturated with this flattened, exaggerated anime style of action. To me, the Super Saiyan Volumes 1 and 2 tapes represent a fully realized parallel universe to hyperpop, though I’d reckon that since they aren’t on streaming, a good deal of these young hyperpop producers have no idea they exist. No shade. But those kids should go listen to “Own Lane” and see what’s up.”

All the same, hyperpop is created by a diverse range of artists—such as quinn, midwxst, Aaron Cartier, and angelus—and many are intentional about the diversity of the scene they’re developing, especially in Chicago. Though the national (and digital) conversation can gravitate towards white artists, the city’s hyperpop scene is driven by many Black and brown artists, and LGBTQIA+ artists in particular. (Many hyperpop musicians name the late PC Music affiliate SOPHIE as a defining influence—not just for her bubbly, kinetic approach to sound design, but for the way she used this palette to explore gender and trans identity).

“When hyperpop was first conceptualized, I initially had an issue with it because it wasn’t racially inclusive and seemed to be the same popularized white artists in rotation,” Andrew Goes to Hell said, “but immediately after its inception, those popular artists took it upon themselves to ensure racial inclusivity.”

Andrew Goes to Hell, who grew up in the Southwest suburbs, became interested in music through his family. “My mom [played] house and RnB… and my Dad was listening to a lot of new wave at the time, along with all the other songs my older brother had on his iPod. I first started getting really deep into creating music when I first started DJing around sixth or seventh grade and started speeding songs up to a faster tempo and uploading sped up ‘remixes’ of songs on YouTube.” These fast-pitched remixes are sometimes known as “nightcore,” a genre that A.G. Cook and other hyperpop artists have cited as an influence on their music. Still, Andrew Goes to Hell describes himself as a “hyperpop-adjacent” artist. “I feel like some of my music could fit the criteria that meets hyperpop, but I don’t think all of it does,” he said.

Even Fraxiom—an artist signed to Dog Show Records, a label run by 100 gecs co-founder Dylan Brady—thinks that there’s no one definition for hyperpop. “I feel like when everyone talks about hyperpop, they have this idea of what it means in their head, and they won’t tell anyone else and they just expect everyone to get it. Because some people mean it like PC Music, Hannah Diamond-type stuff, and some people mean it like cloud rap, and then like you’ve also got like Caroline Polachek, and then there’s full on drum and bass, and just everything is so varied when you talk about the word hyperpop.”

“When I started making this type of music, before the hyperpop playlist was even around,” Fraxiom said, “I would just call it pop music, because what I interpreted all of this stuff as was like me formerly being an electronic artist, and now I want to make things that sound like my interpretation of the Top 40, but also I want to use that influence of like Brockhampton, Tyler, the Creator-type stuff … doing storytelling, and it’s super raw sometimes, like absurd. [But] by the time I started making vocals in 2019, I was really about the heavily autotuned Dylan Brady, Drain Gang, Playboi Carti [sound]…. the more synthetic stuff.”

In conversation with the Weekly, Andrew Goes to Hell also touched on a wide range of influences, including Chicago rappers like Sicko Mobb, Chief Keef, and Stunt Taylor, along with Chicago footwork and house artists like DJ Taye, DJ Slugo, DJ Deeon, DJ Funk, and DJ Trajic. For his part, Andrew Goes to Hell hears the influence of these Chicago genres within some hyperpop. “As time goes on, you’ll find that a lot more hyperpop music will have segmented elements of genres such as drill and alternative rock just in one song alone. It’s funny, because now there are new coined subgenres like ‘hyperdrill’—and it’s exciting to see genres cross and evolve, but [also] give recognition to the source material. I think on a local level, artists are making music with subconscious influences, like footwork or bop and drill, and are implementing them in this new way across different genres. And it really is a beautiful thing to see.”

Both Fraxiom and Andrew Goes to Hell agree that Chicago has an important hyperpop scene—“Casper McFadden, Chase Alex, Bean Boy used to live here, Ivy Hollivana, Hazelboy, Cam Stacey, TYGKO, Mohawk Johnson, Endo,” Fraxiom lists— and one that is growing larger, even if it’s mostly taken place online over the past couple years. Andrew Goes to Hell said that “since the pandemic, a lot of places really shut down and venues are a lot more scarce now, but a few people like Reset Presents are slowly trying to bring more shows with similar bills that once catered to the hyperpop music genre. Pre-pandemic there were many DIY venues always popping up in the South Side and all over Chicago that had diverse bills, but it is taking some time now.”

Fraxiom said that Chicago’s music scene was what inspired them to move from rural Massachusetts to Chicago, where they attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago before dropping out to focus on music. “The moment that made me realize that I needed to be in Chicago if I wanted to make music,” Fraxiom said, “was [when] I was one month into college and I was at this rave, Andrew Goes to Hell was also playing it … I ended up DJing shirtless smoking a joint at like three in the morning… Laura Les [from 100 gecs] was there, Casper McFadden played too. It was the best small show I have ever been to, and I was like, if this is how Chicago moves, I need to be at these like all the time.”

Chicago is the perfect place for hyperpop to take hold, especially given the city’s innovative bop scene, and the city’s penchant for electronic music like house, juke, and footwork. Basically, Chicago bop music—all of Sicko Mobb, Keyani’s “Bop Wit Me,” the late Edai’s “Clout Like Us,” the late Lil Jojo and Lil Mister’s “Episode,” the “Save That Shit” mode of Chief Keef and the “Mollygurl” mode of Lil Durk—is just forward-thinking pop music, as is the music coming out of Chicago’s modern hyperpop scene.

Andrew Goes to Hell, too, sees something special in Chicago’s scene. “In a time where it seems like a lot of people are moving to other creative hub cities like New York or Los Angeles, it is worth so much to take in Chicago for how special it really is. And if we allow a diverse creative community to grow here, we can really share that with the world.”

“I’ve been feeling really nostalgic lately about when I was little and started DJing, and how much I would daydream about moving closer to the city to make music,” he continued. “Whatever music I make in 2022, I really want to capture that feeling of how much I once loved, and still love this city.”

Bobby Vanecko is a contributor to the Weekly. He last spoke with sociologist and professor Forrest Stuart about drill music in Chicago.