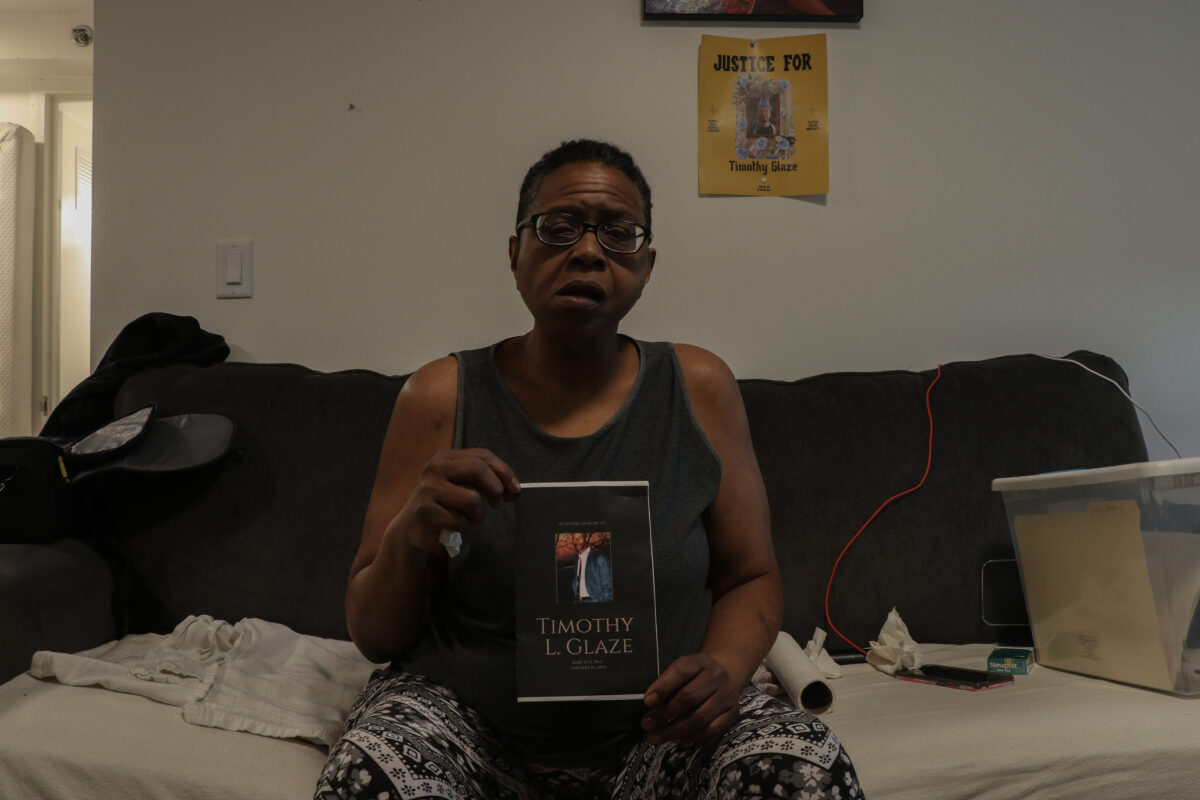

Charlotta Pritchett was four times married and divorced when Timothy Glaze asked her to marry him. And then he asked again. Both times she said no; she knew she did not want marriage again.

“Tell you what, can we be partners for life?” Pritchett recalls Glaze asking her. She agreed. “That was my partner. Little did I know, six years later, his life will be gone,” said Pritchett.

In front of the teal blue door that she used to walk through every day, eleven bullet holes served as a haunting reminder of the night this January when four police officers stepped off an elevator and shot Glaze sixteen times.

He was in the midst of a mental health crisis.

The officers were responding to a call for help, but when Glaze walked glassy-eyed into the hallway, a knife in his hand, officers backed up, three with guns already raised. Within a minute, he was dead.

In 2024, more than 250 calls on average were made each day to 911 in Chicago about a possible mental health crisis, according to public records. The vast majority of these calls led to police being dispatched.

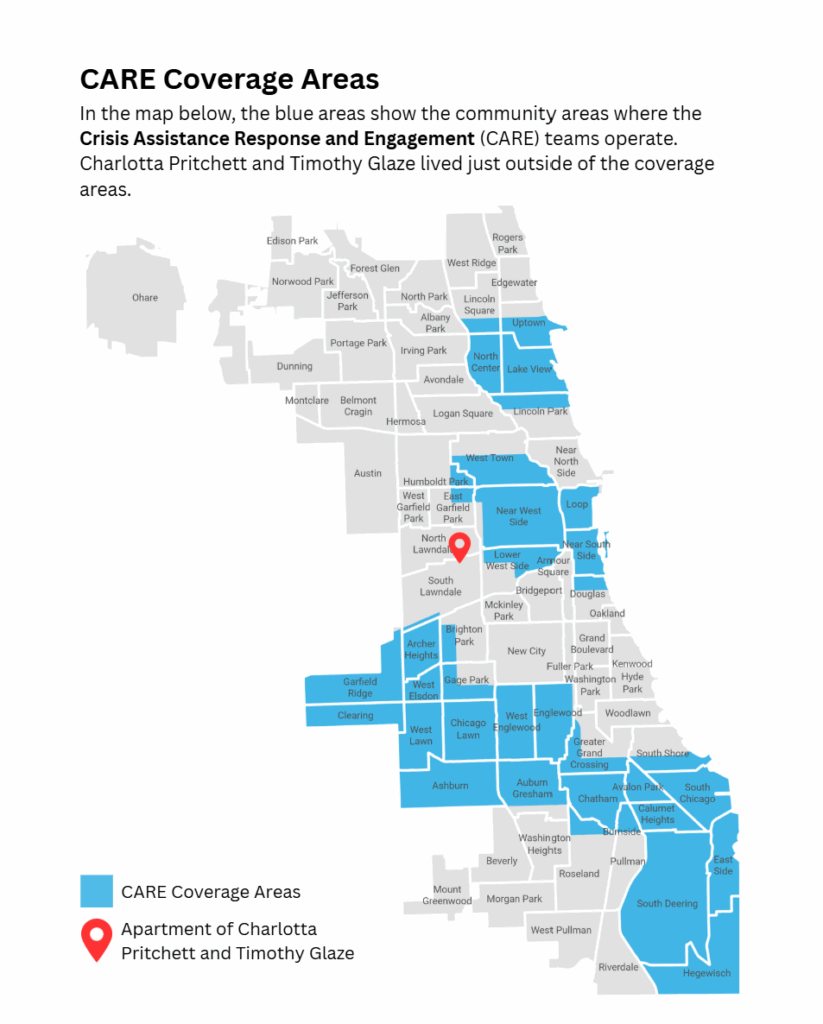

Chicago has sought to improve its response by sending mental health clinicians and emergency medical technicians through the Crisis Assistance Response and Engagement (CARE) program, instead of police, to mental health emergencies in certain areas.

However, recent reporting by MindSite News and the Medill Investigative Lab-Chicago found the CARE program serves only a tiny slice of the city’s needs and appears to be in a state of retreat, rather than promised expansion.

Pritchett’s apartment in Little Village fell outside of CARE coverage areas and her multiple 2am calls to 911 came after CARE’s 10:30am–4pm day had ended. Plus, Pritchett had never heard of CARE and didn’t request a mental health response.

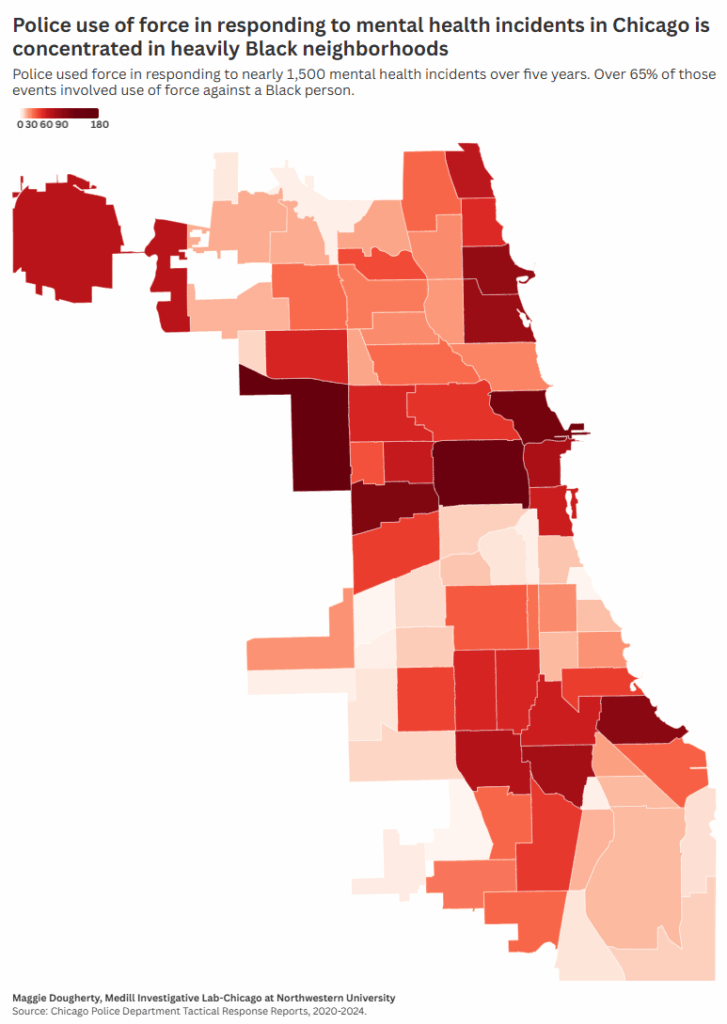

Data obtained by MindSite News and Medill revealed that Chicago police used force to respond to mental health crises more than 400 times in 2024. The encounters occurred disproportionately in Black and Latino neighborhoods, echoing previous national findings.

Although non-Latino Black residents make up around twenty-eight percent of Chicago’s population, more than sixty eight percent of mental health-related use-of-force incidents involved Black subjects in 2024. Another seventeen percent of these incidents involved Latinos. These encounters were concentrated in West and South Side neighborhoods, which are predominantly Black and Latino. Black and Latino people were also disproportionately likely to be arrested during mental health crises that involved force from police.

The Chicago Police Department declined or did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story. The department said they could not comment on Glaze’s killing because of pending litigation, and in response to questions about use of force, provided a link to policies for responding to people in crisis.

What the records show

Nationally, people with serious mental illness are eleven times more likely to experience force during interactions with police officers than those without mental illness, according to a 2021 article in BMC Psychiatry. In many cases, researchers say, police are ill prepared to recognize and address symptoms of mental illness. An individual in crisis may act in ways that are unpredictable or frightening, or that may appear hostile or resistant to officers’ orders.

The mental health advocacy group NAMI, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, recommends de-escalation—“reducing the intensity of a crisis or emotional outburst to achieve a positive outcome and keep everyone safe.” Intervenors should remain calm and use an even tone of voice, keep noise and stimulation levels low, move slowly and gently announce actions before initiating them, NAMI suggests.

“If officers come in running, whether it be guns blazing, aggressive, ‘we’re gonna stamp out this issue’ and barking orders to someone in crisis,” that can exacerbate the crisis, said Craig Futterman, a clinical law professor at the University of Chicago who directs the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project. “Those have been proven recipes for disaster.”

When Chicago police employ any degree of force—from handcuffing to lethal force—they are required to fill out a so-called Tactical Response Report. MindSite News and Medill obtained these records for all of 2024 and the first three months of 2025 via public records request.

Although these records are supposed to include information on the subject’s mental state, officers frequently omitted this information in several violent interactions identified in press accounts as mental health-related.

That was the case in the fatal shooting of Timothy Glaze. Though ABC7 Chicago reported within days of his death that Glaze was experiencing a mental health crisis, nothing in the case file and officer reports released by the Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA) or other documents obtained by MindSite News and Medill noted Glaze’s mental state.

The most common type of force used in mental health situations was handcuffing and other forms of physical restraint. While less harmful than a weapon, handcuffs can cause damage to the soft tissue, nerves and bone structures of the hands and wrists. They also imply that the person has done something criminal, contributing to potential stigmatization or shame.

Chicago police officers were more likely to use a weapon in encounters with a person experiencing mental health symptoms than with others. In more than half of the cases where police used weapons against a person in a mental health emergency, the person was unarmed.

Tasers were the weapon most commonly used against people in crisis. In some cases, such less-than lethal weapons are used in situations where officers appear to see no other alternative.

In January, for example, police reported a Black man in his late twenties standing in the middle of a West Roseland intersection with a knife. The man began walking toward a squad car, blocking its path. When officers exited the car and ordered him to drop the knife, he refused and asked officers to kill him. For the next fifteen minutes, a kind of dance took place—the man would advance with his knife, then retreat backward as officers tried to convince him to disarm.

Finally, the man approached one officer protected by a sergeant holding a shield, and another officer fired his Taser, hitting the man twice and causing him to stumble backwards and drop the knife.

A sergeant used his shield to hold the man on the ground until he could be restrained and placed in custody. He was transported to St. Bernard’s Hospital for mental health evaluation.

Police records indicated that a review found the use of force to be “objectively reasonable, necessary and proportional” and in compliance with the department’s guidelines.

A man in crisis

At the time of his death, Timothy Glaze’s body was riddled with cancer. He was rail thin, carrying only 137 pounds on his 6’1” frame, according to the autopsy report.

“I watched cancer eat him alive,” Pritchett said. “I would see him get out of the shower. It was a skeleton getting out of the shower with skin on it.”

Adding to the emotional turmoil of facing his mortality, Glaze struggled with his mental health in other ways. He told Pritchett that he’d been diagnosed with manic depression, better known as bipolar disorder. She described days when the two of them would be enjoying time together, and suddenly a cloud would come over him. And that, she said, is what happened on the day he died.

Throughout the day, he kept picking up a knife and carrying it around absentmindedly. When she would ask him why, a confused look would come over his face and he would set the knife down, only to pick it back up again a few hours later.

Eventually, he sat next to her on the couch, again holding the knife. But this time, he didn’t want to put it down and would not listen to reason. Pritchett grabbed a screwdriver, just in case. She didn’t think Glaze would try to hurt her, but recognized that he was not himself. And, she remembered, murder-suicide is a real thing.

By the Numbers: Chicago’s Use of Force in Mental Health Cases in 2024

The police department also logs encounters that result in force by officers, and notes whether they include a mental health component. These records show 402 incidents in 2024 where force was used in a mental health situation.

In 2024, 911 dispatchers in Chicago recorded 28,822 calls to 911 regarding mental health issues including mental health-related disturbances and suicide threats and attempts. They logged another 67,796 calls as “check wellbeing,” a category that signifies possible mental health issues.

The police department itself recorded 58,656 calls for service—an average of 160 a day—that it designated as eligible for Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) service, indicating a mental health issue.

That is likely an undercount, however; since officers don’t always note a mental health issue when one occurs. The Timothy Glaze case is an example. His girlfriend Charlotta Pritchett told MindSite News and other media that he had a long history of mental health problems, and he was acting erratically the night she called 911 for help. But the police report of Glaze’s killing by officers makes no note of mental health issues.

Medill and MindSite News analyzed reports on 402 incidents where police used force in responding to a mental health call. Our analysis showed:

- In forty-one percent of the occasions when police deployed force on people experiencing a mental health emergency, they arrested the person in crisis.

- Of the 166 people arrested, 143 were identified as Black, Latino or both. The vast majority of the 166—over eighty-five percent—were unarmed.

- In eighty-six percent of cases when police used force in a mental health situation, the person was hospitalized, often against their will. Officers are authorized to transport such people to a mental health facility with or without their consent to protect them or others from harm, according to department policy.

- When officers deployed a weapon during mental health crises in 2024, they used tasers 80% of the time. Past reporting by MindSite News and Medill has shown that tasers can cause long term damage, and in rare cases, leads to death.

- On at least fifty occasions last year, police data shows a person in a mental health crisis was injured by police before being hospitalized, by tasers or otherwise.

- Over eighty two percent of mental health force incidents resulted in use of handcuffs or other physical restraints. Of the 333 individuals handcuffed, only 139 were placed under arrest, meaning many were handcuffed when they had committed no crime. Of those people, forty-four were armed, generally with a knife or blunt weapon.

At 2:08am, Pritchett called 911 for the first time. At the start of the call, Pritchett primarily addressed Glaze, telling him, “The police are on the phone.” She gave the 911 operator both of their names and the address. “We’ve both been drinking,” Pritchett said to the operator.

Three minutes later, Pritchett called again. This time, she was yelling. She told the second operator that Glaze, knife in hand, had trapped her in a corner and would not let her out of her bedroom. She told the operator that she had a screwdriver.

At 2:18am, four police officers stepped out of the elevator onto the floor of Pritchett’s apartment.

Officer Salah Saleh knocked on the door and announced their presence. The door swung open at his knock, revealing an empty entranceway.

Glaze walked out from the apartment, knife hand coming up and into view as he approached the officers.

“Woah,” an officer said. “Step back.” All four officers quickly backed down the hallway; only one did not aim his firearm at Glaze. The two in front, Saleh and Officer Alejandro Urbano Mateo, fired their weapons eleven and nine times, respectively.

Within three seconds, the two officers fired twenty shots. Sixteen bullets hit Glaze. Four struck his chest. Others hit his thighs, both arms and his stomach.

Four stray bullets traveled down the long hallway—past the doors of eight other apartments—embedding in the wall.

Saleh and Urbano Mateo flipped Glaze’s unresponsive body over to cuff him, hitting his head against the wall in the process. Only then did they call for an ambulance.

“I got blood on my hands,” Urbano Mateo said in the body camera footage.

Eighteen seconds after officers entered the hallway, Glaze was dead.

Pritchett heard the shots from a neighbor’s apartment, where she had taken refuge to wait for police.

“My blood just turned ice when I heard all the shots,” said Pritchett. Her neighbor looked at her and said, “I’m sorry, but your friend is dead.”

Glaze’s body was transported to Mount Sinai Hospital and he was declared dead at 2:51am.

Decades of deadly force

Chicago has been under fire for decades for its history of deadly and non-deadly force against Black and brown individuals. In 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) opened an investigation into Chicago police practices following the killing of Laquan McDonald, seventeen, a Black high school student who was shot sixteen times in the back as he walked away from police while holding a knife and acting erratically.

The DOJ found a pattern of civil rights violations by Chicago police including unconstitutional use of force, and in early 2017, the department and the city agreed to develop a consent decree mandating reforms. A week later, Donald Trump assumed the presidency and his administration soon abandoned that effort.

Then-Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan stepped into the breach and sued the police department, resulting in the consent decree that tracks the department’s performance in multiple areas, including how it responds to people experiencing mental health crises. The decree also requires officers to de-escalate potential applications of force and encouraged the creation of an alternative to police response. Since 2019, the department has been required to reform how it trains officers, and to document and hold officers to account for their use of force.

“CPD officers may only use deadly force as a last resort,” the decree stated. It further required that officers using firearms take “reasonable precautions” to protect subjects other than the target. As of December 2024, the department is in full compliance with only sixteen percent of the consent decree’s hundreds of requirements.

After Trump reassumed the presidency this year, he signed an executive order negating other cities’ police-related consent decrees. The Chicago consent decree, however; remains in effect and is overseen by an independent monitor. Despite the decree, police use-of-force incidents involving mental health have increased nearly sixfold over the past decade.

Two lives for the price of one

Timothy Glaze’s death comes almost ten years after McDonald’s and the parallels are striking. Two Black men impaired by mental illness and intoxication, each holding knives, killed by Chicago police officers firing sixteen shots—although neither was an imminent threat to those officers.

Pritchett, who said she used to have a cordial relationship with police, no longer sees Chicago’s law enforcement system as serving her or other Black people.

“I will never call 911 again in my life, because they took Timothy’s life,” said Pritchett. “That’s not what it’s supposed to do.”

She now fears that if she leaves her apartment, she’ll run into the officers who killed Glaze. Both appear to be back on patrol in her neighborhood, since they appear again in police use-of-force data for March. Pritchett takes Ubers to the grocery store instead of walking and tries not to go out unaccompanied.

“I would want them to look in my face and know how you’ve destroyed me, how you’ve traumatized me,” Pritchett said of the officers.

Isaiah Jackson, an activist with the group Dare to Struggle, questioned why officers are allowed to return to patrol when COPA, the police review board, has not yet completed its investigation.

“If the investigation is ongoing, why are these people back on patrol?” Jackson asked. “What is the significance of an investigation if they’re allowed to return to work before you have the outcome?”

For months after her partner’s death, Pritchett was faced with the memories of the worst day of her life. For five months, the Chicago Housing Authority refused to move her to another empty apartment so she would no longer have to walk over the spot where Glaze was killed. She was finally moved to another building in late June after her attorney intervened.

Building management even asked her to pay for the damage to the hallway, Pritchett said, telling her that she was responsible for Glaze, as he was her guest.

Without Glaze’s income, Pritchett said, she is struggling to pay for groceries and other costs and relies on donations from a GoFundMe, which has had no new contributions since April.

In a recent interview, she described Glaze as a gentle soul and caretaker who would carry her groceries for her and do the cooking.

She played a video on her phone of Glaze dancing to music in the kitchen and showed photos of them together.

“He always did things like that to make me smile,” Pritchett said. “They’ve taken that smile.”

She wants people to remember him as she does.

A wrongful death lawsuit has been filed by the mother of Glaze’s two children alleging that “The City of Chicago has a custom, practice, and policy of ignoring the rights of individuals who are in psychological distress, escalating matters, and causing deaths.” Pritchett has struggled to find an attorney to represent her in a similar wrongful death lawsuit; she is not a plaintiff in the suit filed by his children.

Now, Pritchett has joined activists from Dare to Struggle demanding that the city and Mayor Brandon Johnson acknowledge and provide accountability for the killing of Glaze and other victims of police violence.

In April, Johnson’s administration placed flyers around Pritchett’s building advertising a planned visit by the mayor to discuss safety concerns with senior residents. The flyers did not mention Glaze by name. Dare to Struggle and residents of the building organized a protest, but the mayor did not appear. Since then, the group has continued to seek explanation from Johnson about why the two officers are back on patrol. They’ve confronted the mayor at community meetings—and were escorted out by security on at least one occasion. Although she does not feel listened to, Pritchett said she is not giving up.

“He would be so proud that I’m trying to fight for what’s right, and that’s justice for him,” Pritchett said.

“I could almost see him sometimes, when I’m at the State Attorney’s Office and I’m talking about his life, I can almost feel him next to me saying, ‘Way to go, babe.’ You know, ‘let me rest in peace, because I’m not.’”

Additional reporting by Medill students Hope Moses, Ashley Quincin, Sam Biggs, Margarita Williams, Jasmine Kim, Tyler Williamson, Mariam Cosmos, Emma Sullivan and Charlotte Ehrlich.

Maggie Dougherty is a freelance journalist based in Chicago specializing in data-driven investigative journalism. She is also a graduate of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, where she specialized in investigative reporting.

Skye Garcia is an investigative journalist based in New York City. She is a graduate of the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, specializing in data and investigative journalism.