Sarah Morris’s 2011 film “Chicago” opens with the assaulting beats of manufactured electronic music. Bright images of rainbow-colored programs on computer screens fill the darkened theater with an eerie glow. Morris makes the audience wait through several minutes of this visual and aural chaos before offering up a glimpse of the titlular city. She first shows Chicago’s fabled skyline from across Lake Michigan, letting us soak up the familiar jungle of steel, glass, and concrete from afar, before plunging right into the midst of the towering buildings themselves. The camera flits in between buildings, allowing a bit too much time for admiration of the architecture downtown.

The electronic music continues throughout the length of the film. This is the only sound the audience hears for the next sixty minutes; Morris includes shots of conversations, but all the audience can hear is the music’s constant pulse as the people onscreen speak unheard words. The film also uses beautiful close-up shots that evoke the intrusive feeling that Morris is revealing what is usually hidden to the everyday observer.

“Chicago” might have been more approachable if Morris had showcased images of what the average Chicagoan sees—and the average Chicagoan is not a businessman in the Loop. Morris neglects to explore the neighborhoods further south and west, where the workers she shows so prominently retreat when the day is done.

Throughout the film, Morris takes the audience on a journey through the offices of “Ebony” and “Playboy” magazines, inside the industrial inner workings of a meat processing plant, Fermilab, and the Chicago Tribune’s news printing machinery. The scenes—shot both during and after a typical workday—are remarkably similar in all three of these places.

But Morris’s focus on large-scale downtown industry overlooks the importance of the people who make these industries run day after day. Her heavy focus on business could have benefited from some variety, perhaps by showing some of Chicago’s artistic endeavors: escaping the factory and delving into a locally-run gallery somewhere south of the Loop.

Morris visits two different restaurants downtown to showcase the ways Chicagoans like to eat. Surprisingly, deep-dish pizza fails to make the cut. Morris instead stops by Manny’s Coffee Shop, a Jewish deli, during the lunch rush, and an unnamed experimental upscale restaurant at dinnertime whose kitchen looks like a chemistry lab.

The attention Morris pays to the act of sitting down to eat a meal—a rather common aspect of human life—reveals just how different this communal experience can look. At Manny’s, we see fluorescent-lit cases filled with pre-wrapped slices of pie and middle-aged men hastily slapping together sandwiches, which are then consumed by mostly lower-middle class customers in a bland beige room. At the high-end restaurant, the chefs meticulously assemble miniscule plates that look more like edible art than dinner; waiters dressed in black bring the plates to smartly-dressed diners waiting in a sleek black and silver dining room. Morris’s examination of Chicago food could have used some cultural variation, or at least a trip out of downtown.

It’s difficult to know exactly what Morris aims to accomplish with “Chicago” from viewing the film alone. Fortunately, on the night of “Chicago’s” premiere at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Morris agreed to talk about the film with Dieter Roelstraete, Manilow senior curator at the MCA. Morris, a slim woman in her mid-forties, was dressed in black pants and a blazer with a large black and white silk scarf blooming around her neck. A sleek brown bob framed her face. It seems as though Morris puts the same exacting scrutiny to her appearance that she does to her films and art—no element of her carefully crafted image was out of place.

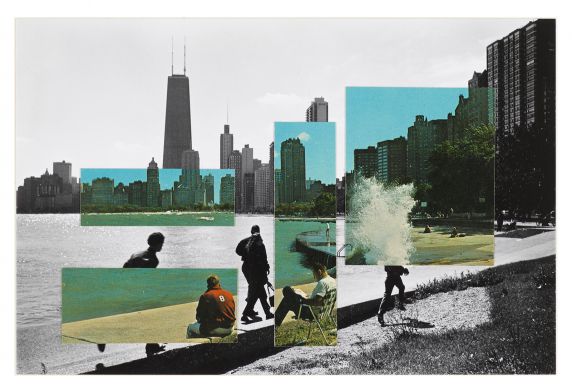

One of Morris’s first moves was to correct Roelstraete for calling her series of city-based films “portraits;” this is a term Morris herself doesn’t use, as it is “much too utilitarian.” Morris’s objection to this term is a rather interesting one. “Chicago” is a film that does seem to create a visual portrait of the city—or at least a portrait of what an outsider might think of when they think of Chicago.

Yet Morris stated that she based “Chicago” off of what first comes to her mind when she thinks of the Windy City—its political history, industry, meatpacking, advertising, publishing, and architecture. Specifically, Morris noted that Chicago is constantly filmed, so she wanted to confront her audience with a different filmed look at the city.

Still, many members of the audience were unsatisfied with Morris’s answers. One, in particular, asked if she was aware that Chicago is often called “the city of neighborhoods,” as Morris essentially ignored all neighborhoods other than the Loop. Morris said she was, in fact, aware of Chicago’s many neighborhoods, but wasn’t at all interested in filming them. “I’m not interested in creating portraits,” she reminded us once more. Morris said “Chicago” was guided by her “automated interest” in the city, so she only researched the aspects of Chicago of which she was already aware.

Morris showed no interest in learning about Chicago’s people, places, and things that weren’t already on her radar as an outsider. For Morris, these films are hardly more than “an excuse to investigate a place, meet new people, and talk to them.” A Chicagoan can hardly help but ask how much “investigation” Morris really did.

Chicago is bigger and more complex than Morris shows. It’s a shame that she runs from this diversity rather than embracing it and using Chicago’s beautiful complexity to deepen her storytelling. Morris’s purportedly “unified perception” of Chicago as a centralized, industrial powerhouse may have some truth to it—but there is more to Chicago than the Loop’s skyscrapers and the businessmen walking down State Street. Morris includes several scenes of a sports car driving into and out of the Loop, but she never asks us to wonder where the driver is coming from.

“City Self” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 220 E. Chicago Ave. Through April 13, 2014. Tuesday, 10am-8pm; Wednesday-Sunday, 10am-5pm. Suggested general admission $12, students and seniors $7, members free; free admission for Illinois residents every Tuesday. (312)280-2660. mcachicago.org