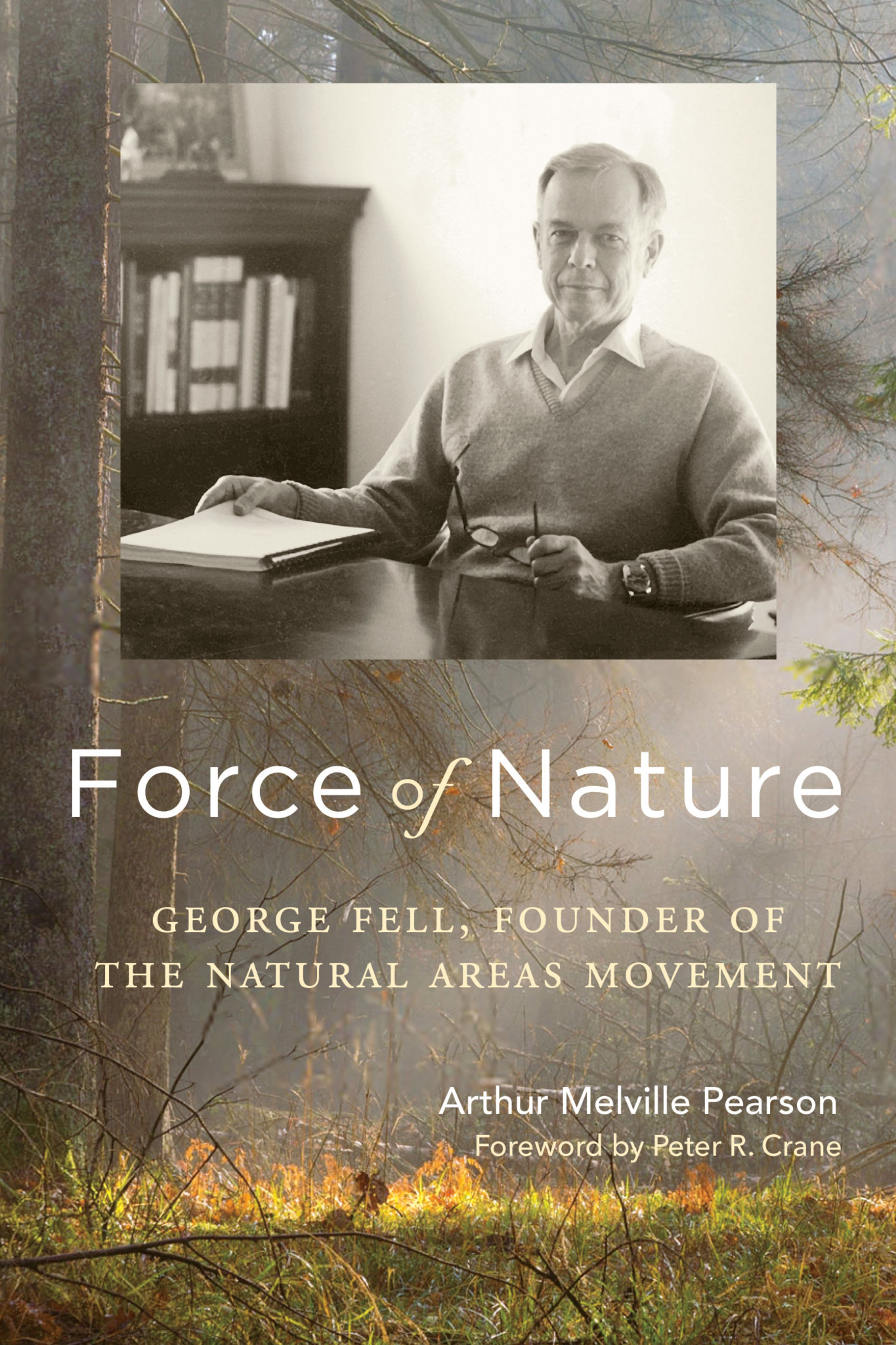

When it comes to the telling of a life, there are things that our surroundings know more than we will ever do. Arthur Melville Pearson, a conservationist, pays clear attention to this in Force of Nature, his biography about George Fell, the founder of the natural areas movement. This post-World War II movement initiated enhanced communication and collaboration among people concerned with the protection and study of natural areas and natural diversity. Through Pearson’s attention to place, the story of this obscure conservationist figure is told with the conviction that the inextricable force of nature drove all of his endeavors.

Pearson first learned of Fell when he was commissioned by the Natural Land Institute to write a short biography about him for inclusion in its fiftieth anniversary publication. Struck by the similarity of their interests, Pearson continued researching Fell, consulting archives and people in Fell’s life to put a longer biography together. The son of a botanist father, Fell was surrounded by the pleasure of caring for natural life his entire childhood. He went on to work in the Civilian Public Service during the war, then found his stride in conservation work at The Nature Conservancy, the largest conservation organization in the world.

Pearson writes the book with a removed, academic approach. “In this way, form follows function because it provides this particular individual the degree of distance he maintained from everyone in his life,” Pearson told me. However, Pearson allows room for Fell’s personal philosophy and sentiment to seep into his history by framing several chapters with details of the landscape Fell worked to protect at each point in the timeline. He particularly spotlights Aldo Leopold, a founder of the science of wildlife management who became Fell’s main academic influence. Fell took up Leopold’s notion of “a land ethic, or some other force which assigns more obligation to the private landowner” from Leopold’s essay “The Land Ethic.” Fell’s steadfast commitment to that obligation made him active and hardworking but put him at odds with several of his coworkers.

He was challenged by a fellow board member who was as dedicated to conservation efforts as Fell, but had a more hands-off approach. The board member ultimately pushed Fell out of his position, driving Fell to leave Washington and return to Rockford, Illinois, where he started the Illinois chapter of The Nature Conservancy. It was this chapter that allowed him to advocate for the Illinois Natural Areas Preservation Act and the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission, initiatives that sustained his need to serve until retirement.

Pearson’s own conservationist efforts reside in nature preserves as well as his neighborhood, the historic section of Pullman. To him, the connection between preserving natural land and historical sites is a “recognition of the full range of beauty,” a recognition he sees in both George Fell and himself. Between Pullman, his background in the arts, and his work as the Chicago Program Director of the Donnelley Foundation, where he oversees both arts and land conservation programs, he finds that “if there’s an invitation to go find your own way into beauty, then you can meet it on your own terms and define it in your own terms.”

Fell’s determination and unwillingness to quit after several setbacks in his leadership vision proves to be unflinchingly relevant to the challenges of achieving stalwart preservation that conservation organizations are facing today. In terms of environmental conservation now, the National Parks, originally a foil to the natural areas movement, are of particular importance. The Parks are able to educate people about difference in landscape and how to apply that knowledge to navigating a local nature preserve. This can be challenging, Pearson noted, since in urban settings, people often establish a psychological and emotional distance from natural areas they may also be physically distant from.

“It’s hard when things like this are fundamentally devalued and gutted,” Pearson said. “With the EPA and NEA being cut to bone, I think it is a powerful disincentive for people to go outside themselves to appreciate the most mundane and pedestrian things as opposed to enriching our lives in an expensive way. I think we’re seeing the pushback in the artistic community as opposed to the conservationist community, the drive to push back up from the grassroots to say ‘this is why this is important’ and ‘we’re committing to this to make sure this remains vibrant and alive.’ The more people put something down, the more we’re gonna invest in it.”

Pearson is no stranger to investment, as the writing process for this book took him about fifteen years. In his interviews with Barbara Fell, she painted George as a hero, which Pearson knew was not an accurate way of telling their story. With Barbara’s passing in 2015, Pearson could continue the more sobering story that was coming together. With the long-awaited publication of this book, he’s honoring its message by dedicating it to Barbara and visiting fifty Illinois nature preserves this year.

He’s already hit fifteen. “In each place, there’s something that tells us about George’s story. Most people don’t know about these places, they don’t care. But one by one, the rich biological heritage that we have just goes away. Every time you go to a preserve, there’s some element of the story that is referenced, so doing this accomplishes most of these things. It’s a way to keep the story alive. It’s also a living addendum to the book.”

In terms of where this book stands in the field of conservation history, Pearson thinks “there’s a gap on that shelf.”

“I think Force of Nature really slots in nicely ’cause there is an art to conservation history,” he said. “I think this was a smile with a missing tooth, if you will, and it’s nice to fill that smile in.”

Arthur Melville Pearson, Force of Nature: George Fell, Founder of the Natural Areas Movement. University of Wisconsin Press. 216 pages. $26.95. Out April 18.