Doing Time investigates the daily life of people navigating court and jail. We focus on Cook County, home to the country’s largest single-site jail, and the courts that order people’s release or jailing. Readers of this series will hear from insiders, formerly incarcerated people, loved ones, policy experts, and government actors to establish the forces that shape the everyday experience of doing time.

“No keys, no card, nothing.”

On a hot night last August, Antuan found himself standing outside Cook County Jail in Little Village, wondering how he was going to get home at 1:30am.

“The thought process at the moment was like, ‘Wow, it’s pretty late to be being released from jail,’” Antuan said. “Everything’s not running right now, like buses, the trains are shut down because it’s so late.”

With no other options, Antuan walked more than half a mile to Western Ave. and took the 24-hour bus south to his apartment on 35th street. There, another challenge awaited.

“You don’t have your car keys, you don’t have your door keys, you don’t have your debit card, you don’t have anything,” he said.

He knocked on a neighbor’s window. Despite it being the middle of the night, Antuan’s neighbor and property manager helped him back into his apartment.

As it turned out, getting home was the easy part. Since his debit card was still in the hands of the police, he had no way to get money. Withdrawing money from the bank or collecting his property required a photo ID, which the police also had. He had no way of paying the $200 ticket an officer had written during the arrest.

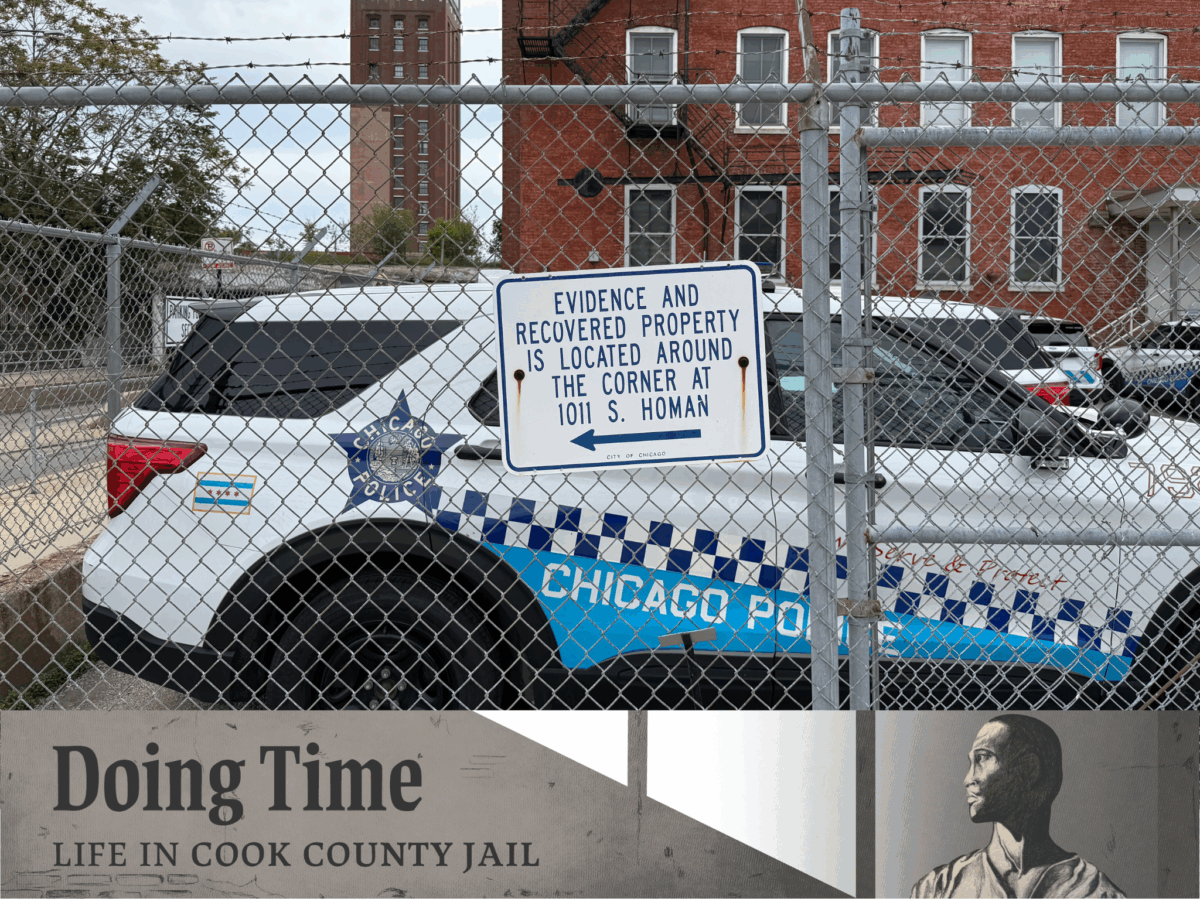

Antuan went to the police station where he was first arrested to collect his stuff. But getting it back wouldn’t be so simple. Since he’d been in jail for more than ninety-six hours, his property had been transferred from the precinct where he’d been booked to a Chicago Police Department (CPD) facility in Homan Square, six miles away on the West Side.

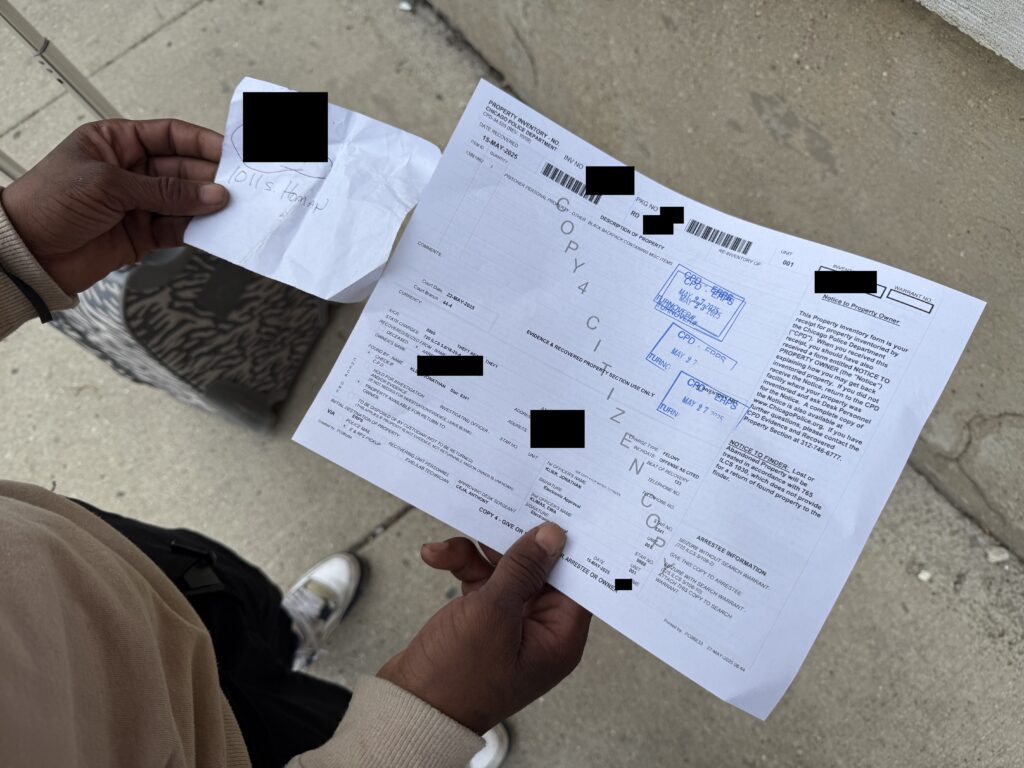

Like the tens of thousands of people arrested in Chicago each year, Antuan would have to navigate the labyrinthine property system to get his ID, debit card, and keys back. He’d have to do it quickly, or risk losing his personal belongings forever.

ARREST

During arrest, police officers confiscate people’s property, including medicine, keys, wallets, and phones.

Officers then take them to a police station for processing. For some arrest charges, people are released directly from the police station. For others, people are transferred to the Sheriff’s custody in Cook County Jail.

Chicago police and the Cook County Sheriff move people separately from their property.

The departments’ policy directives both instruct police officers to keep most property at the precinct but to send essentials—such as keys, credit card, medicine, wedding rings without stones—to the jail. At release, people are supposed to exit the jail with their essentials.

Everything else a person has on them when arrested is kept at the precinct where they were booked. Per CPD policy, this non-essential property should stay at the precinct for at least ninety-six hours before being moved to Homan Square. Suburban police departments have separate property policies.

That directive does not apply to evidence taken by police or property seized under civil asset forfeiture According to the Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts, 90 percent of asset forfeiture cases involve a vehicle and most underlying cases are for non-violent crimes like drug possession or driving without a license. For this story, we focused solely on personal belongings not considered evidence or asset forfeiture.

Interviews with people released from Cook County Jail and the Weekly’s review of property records obtained from CPD via a public-records request show that the police take a staggering amount of personal property from Chicagoans like Antuan. In the first six months of 2025, CPD took more than 89,000 pieces of property from Chicagoans during arrest. One out of every five pieces of property was not recovered—11 percent was destroyed and 3 percent sold. Most sold property was jewelry people were wearing at arrest.

In some cases, destroyed items included essentials like keys, government IDs, and credit cards.

The data shows that in just the first half of this year, CPD destroyed about 9,700 items they took from arrested people. Nearly half of it was clothing: 800 hats, hundreds of jackets, pants, and sweaters, and fifteen pairs of shoes their owners would never see again. Police destroyed nearly 900 cell phones and almost 500 wallets—along with twenty-seven food stamp cards, twenty Ventra cards, twelve government IDs, five inventory receipts for property from previous arrests, five social security cards, and five birth certificates.

There was also one destroyed button that read: “I Am Dad 365.”

Municipal police departments in Cook County such as CPD have slightly different policy directives from the Cook County Sheriff’s Office (CCSO). CCSO’s property policy does not place a limit on the number of credit cards, transit cards, and IDs that can be stored at the jail, for example. Meanwhile, CPD’s policy on essential items only allows for one public transportation card, one government ID, and one credit card to be transferred to the jail.

CPD did not answer questions about whether it violated its policy by keeping and later destroying essential items like government IDs.

“Chicago Police could easily address the hardship caused by people’s property not being transferred to the jail by transferring fewer people to the jail,” read a statement provided by the Cook County Public Defender’s Office. “People released directly from police stations with a notice to appear in court are in a far better position to consult an attorney and make plans for their employment and for childcare in order to appear at initial court hearings.”

COLLECTING PROPERTY FROM POLICE PRECINCTS

When people are released at the police station, they can collect their property before leaving. In Chicago, property desks at each police station are open 24/7, but suburban police departments can have shorter hours, with some closing as early as 2:30pm.

Jacob (whose name the Weekly has changed at his request), was arrested in suburban Maywood two days before his twenty-second birthday. His first stop was the hospital.

“I got stabbed before I got arrested,” Jacob said. “So I sat at the hospital for, not even a whole day, [almost] a day, and then they discharged me from the hospital. That’s when I took the ride.”

Jacob’s “ride” was police driving him from the hospital to Cook County Jail. At the jail, sheriffs said they could not take Jacob and his property. So the police drove Jacob over half an hour from the jail to Maywood police station, processed his arrest, and drove him back to jail.

Jacob was released at around 2am, two days after he arrived at the jail and four days after the stabbing and subsequent arrest. The street lights were out. He was wearing the same clothes that he was arrested in, cut up from being treated at the hospital, and by that time worn for four days in a row. Like the other interviewees, he had been released with none of his personal belongings.

“I didn’t have nothing. Not a phone, not a bus card, not a shoestring.”

Jacob waited for his ride to get there, concerned for his safety in the middle of the night in an unfamiliar neighborhood. All he wanted to do was get home and let his people know he was okay. When his ride found him, they went to the Maywood police station to collect his things, getting there around 3am.

But it turned out the Maywood property desk was open during business hours, from 9am–5pm.

“They told me I can’t get my stuff until ten o’clock the next morning.”

Exhausted, but with no other option, Jacob went home and returned the following day. He was able to get back his personal belongings—or most of them, anyway. In those three days the police had lost his shoelaces.

COLLECTING PROPERTY FROM HOMAN

“Open to the public, Monday-Friday, 8AM-3PM” reads a sign next to a plain, unmarked black door at the Homan Square police facility. Aside from a couple signs at the nearby high school and police parking lot pointing in the direction of the door, there is no other way to tell that this is the main property desk for the entire city of Chicago.

Just after 8am on a Tuesday morning in May, Zachary walked south from the Green Line towards Homan Square. He arrived at the unmarked black door only to find it closed.

A few minutes after 8:30am a woman holding a large pink slushie and wearing a Chicago Police Department uniform arrived, unlocking the door and letting the people waiting outside into the property room.

That morning, at least four people came looking for the property desk. Everyone needed help finding the door and figuring out how to get in. It took most people over thirty minutes to get their belongings.

Zachary emerged from the property room confused.

He had been arrested the previous week and released two days later. When he was arrested, Zachary, who is unhoused, had all his belongings and hygiene items in a black backpack that was processed as property by CPD.

Zachary started looking for his backpack around 7am at the CPD First District in Bronzeville, where he was booked. Officers looked up his property and explained it had been moved to Homan Square. Officers wrote out his property number and the address on a small sheet of paper, and Zachary took the Green Line train over an hour to Homan Square.

But at Homan Square, they told Zachary his property was at the First District. They printed out a new copy of his property receipt and sent him back south.

“I just came from there,” Zachary said. “I already been there. [Inside Homan Square] he’s saying it’s still there, but the lady at that front desk told me it’s here.”

According to CPD’s property records, Zachary’s backpack was destroyed.

Zachary was arrested for retail theft. This is the second most common charge for people whose property is destroyed after an arrest. People arrested for retail theft made up 4.7 percent of those whose property was taken and 8.6 percent of people whose property was destroyed.

GETTING SOMEONE ELSE TO GET PROPERTY

As of October 29, there were 4,502 people in Cook County Jail who had been incarcerated for more than thirty days, and 155 people who had been incarcerated before a conviction or trial for more than five years. When someone is in jail, their property is destroyed after thirty days unless someone outside goes to pick up property in their place.

CPD’s public directive on property seized by the department says incarcerated people can retrieve property by “sending a letter instructing [CPD Evidence and Recovered Property Section] to whom the property should be released, identifying the name of the facility where you are jailed or incarcerated, and providing a copy of your receipt and your photo ID.” The instructions do not include guidance on how someone in jail could print and mail a copy of their photo ID.

In Cook County Jail, people fill out a form that must be physically picked up from the jail by a visitor who can then go to a police station to collect property. “Any individual in custody at the Jail may request to have a person of their choice pick up their property held by the Chicago Police Department by simply letting their Correctional Liaison know when they visit the living unit in the morning,” read a statement provided by the CCSO spokesperson. “The Correctional Liaison will then have the [inmate in custody] sign a property release document and the release document will be in the lobby when the visitor arrives.”

After an incarcerated person finds someone to gather their property and shares this legal letter with CPD, their loved one has to travel to Homan and navigate the property pickup.

Losing property “creates a whole ‘nother hassle, another way you have to spend money,” Antuan said, “because now you have to try to retrieve birth certificate, ID and social security card all over again as well as your cell phone and whatever vital information that was in that phone…Everything is just meant to create more anxiety for you. For something that you own.”

“It’s like, wait, I own this stuff.”

PROPERTY DESTROYED AFTER THIRTY DAYS

Antuan was released without phone, keys, or ID on Friday night and made it to Homan Square first thing Monday morning.

Picking up property requires “owner’s copy of the inventory and proper proof of identity,” but Antuan’s photo ID was in his wallet. It took some back-and-forth, but he was able to convince the officers to return his keys, ID and debit card along with the rest of his property.

Despite the long bus rides and waiting, Antuan felt lucky his property was intact.

Chicago Police Department policy is to keep property for thirty days. After that, it is considered abandoned and can potentially be disposed of. According to the Chicago municipal code regarding seized property, it can be disposed of in three ways: property can be forfeited to the city for its use, it can be destroyed, or it can be sold through online public auction. The CPD superintendent makes that decision.

“Let’s just say you have to happen to sit in jail for maybe forty-five days,” Antuan said. “They’ll destroy your property, ID, social security card, cell phones, everything, your wallet, they’ll destroy it. They’ll say that you have to have, like, a family member come and pick it up. And there’s situations where people don’t have family members or loved ones to go pick their things up, and then your property will be destroyed.”

Micah Clark Moody is a PhD candidate in Sociology at Northwestern University. She has investigated pretrial jailing systems in Michigan, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

Maheen Khan is the Director of Technology at the Invisible Institute. She has been a part of the mutual aid group, Chicago Community Jail Support, for four years.