Hermene Hartman is a Chicago publisher who runs N’DIGO magazine, a publication focused on black perspectives and experiences. In 2005, Hartman honored Muhammad Ali with the lifetime achievement award at N’DIGO’s 10th annual gala. She spoke to the Weekly about how the event unfolded, what Ali meant to Chicago, his introduction to then-Senator Barack Obama, and how the Champ will be remembered in his once-hometown after his recent death.

We honored [Muhammad Ali] in 2005 at the N’DIGO gala. He received the annual lifetime achievement award. That’s where I got to know him up close and personal. That particular event we were celebrating our tenth anniversary. It was at Millennium Park.

I told him how pretty and wonderful I thought Millennium Park would be. I painted a picture, and I also painted the why: Because we love you. Chicago loves you. The people of Chicago love you. Let me honor you. You’ve earned it. You deserve it. Let’s do it.

There was a lot of turmoil when Ali was in Chicago, and when he lived here, he had lost his title. He’d never boxed here. He was so revered and so loved by the people here.

He was Ali. He was witty. He was charming. He was charismatic. He was on point. He was purposeful, he was meaningful, he was serious, he was playful, he was all of that. He was still the champ.

He came to the office two weeks in advance and came to that office every day to contribute. He came and met with us, brought lunch one day. He did magic tricks. The first day he came we were actually putting out a paper and he wouldn’t leave because he said he wanted to help. I kept saying to him, I’ve really got to do work today and I don’t have time for you. He was like, “There’s always time for me, I’m Ali. I’m helping.” And so we were printing out pages and we gave him pages to read and approve. After they were really, really approved we gave them to him. We made him part of our team.

One day I said OK, here’s a real job for you: I need you to go raise money. The next two or three days, he had lunches with friends and he raised money. He did it for the gala—sold tickets.

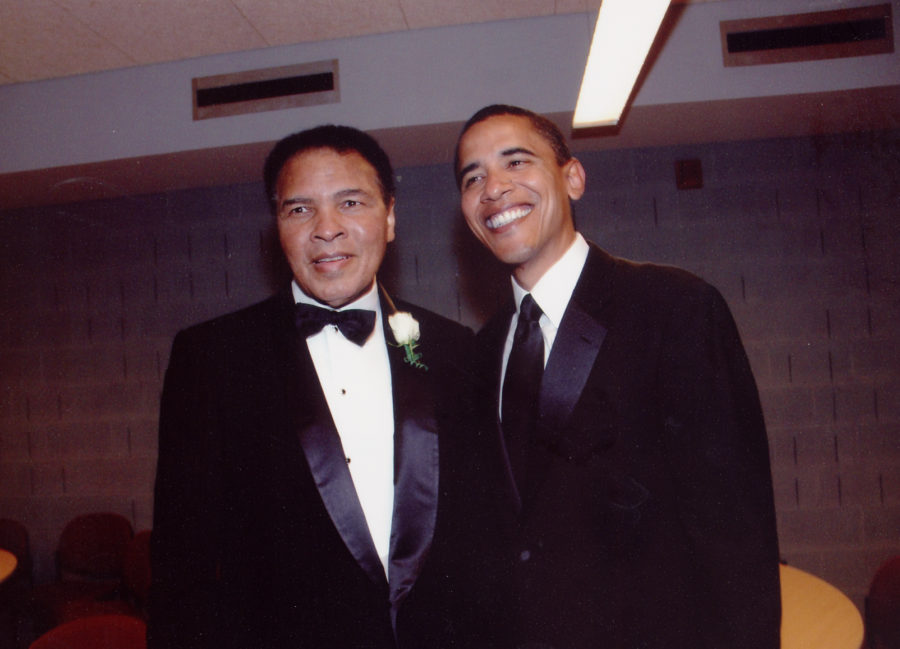

That year, Barack and Michelle [Obama] were the chairmen of the gala. I knew Ali was a hero for [Barack]. On his wall in his state senate office, he had a picture of Ali in the ring. The other picture on his wall was Abraham Lincoln. He was a real fan of Ali. So backstage we made sure that they met. They did and Ali started boxing with him. Ali was being gracious with everyone. He liked to box with the men. Reverend [Jesse] Jackson was backstage and he was boxing with him. That was the thing he liked to do.

The South Side is like a little city, really. Jesse Jackson, Barack Obama, Ali, and Minister Farrakhan all lived and worked in about a two-block radius.

[For Ali, the South Side] was home. He got married, had children, had a mansion in Kenwood. It was just home for him.

Chicago is a political, racial town. It was racial. Mayor Daley did not want Ali to fight here. He was not the kind of black guy that Daley liked. He was not subservient to Daley. So Daley did not allow the [professional fighting] license to be awarded. The Daley strategy in thinking was, “Don’t let anything mount on you. Don’t let anything grow. Kill it early.” That was part of the squashing of Ali in Chicago. Ali said, fine, don’t fight in Chicago? OK, fine. That’s the greatness of this man: He gave a punch but he took a punch. He took it in the ring, but he took it outside of the ring.

When Ali was in the throes of his discontent, not going to Vietnam to fight the war, that was very, very controversial. Some people understood it, some people didn’t.

White people have problems with black people who stand up and fight racism. Black people fight racism where they find it. White people don’t fight racism, they give racism. That’s a major psychological, philosophical difference. So the racial divide on Ali was the black people understanding it and white folks not. Why should I go fight for your imperialistic country for freedom for some people that have never done anything to me, and I come back home after the fight and sit on the back of the bus or be denied rights? Why should I do that? That was a very basic, fundamental question that Ali raised that no one could answer. Of course the answer was you should not be bold, you should not be brash, you should be docile and be the good American, and Ali rebelled.

As we look at history retrospectively, Ali was correct. But at the time, that was a most controversial decision.