Chicago Hip-Hop Heritage Museum cofounder Darrell Roberts often finds himself having to set visitors straight when it comes to the focus of the Grand Boulevard-based institution, which opened in 2021.

Roberts, a Roseland-raised graffiti writer nicknamed “Artistic,” says some tour goers are expecting that rap legends Notorious B.I.G. and Tupac Shakur are prominently featured in the museum. He kindly reminds them that the building is a Chicago hip-hop museum—not a New York or Los Angeles one.

“When people come in and see the entirety in one space, people say stuff like: ‘We didn’t know Chicago had this much history.’ They’ve never seen anything representing us,” Roberts said. “We went ahead and decided to convert this thing into an actual continuing exhibit and then we created the name Chicago Hip-Hop Heritage Museum. We’ve been rolling ever since.”

Roberts doesn’t blame those folks for their “conditioning,” as he put it. After all, he remembers New York’s iron grip on hip-hop in the public imagination and its effect on how other cities see themselves in the battle for respect.

“My room was filled with New York, and I knew the history. I knew more about New York than I did Chicago. And I didn’t realize that it had conditioned me because [Chicago] hip-hop wasn’t readily available.”

Chicago hip-hop got no love from the media. “You couldn’t access ours as easy as you could New York’s. New York’s was everywhere, right? Front cover of magazines, books, TV, and the movies. Chicago doesn’t have a hip-hop movie.”

Locally, househeads often looked down on hip-hop, Roberts says. He recalls the early subculture clashes between househeads and hip-hop purists stemming from the former genre being created locally, while the other traced back to New York.

“I didn’t realize this back then, but I feel that people from the house community [enjoyed] having ownership of house being created in Chicago, whereas hip-hop wasn’t,” said Roberts. “[Househeads] pretty much saw a predominantly New York thing—so people rejected that.”

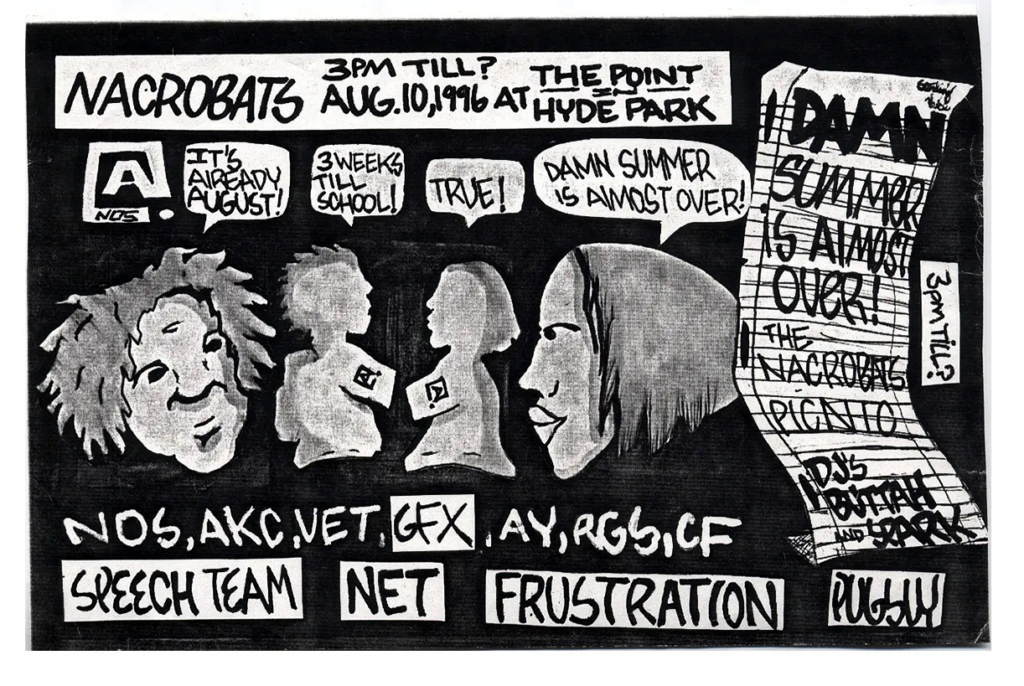

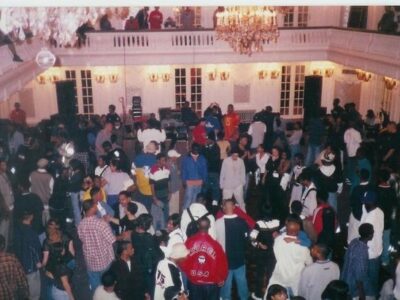

The Chicago Hip-Hop Heritage Museum is the most comprehensive space celebrating and preserving the city’s hip-hop scene to date. Throughout the two-story building, visitors can see party flyers (known in the day as “pluggers”); concert posters; mixtapes and CDs; graffiti pieces; photos of Chicago rap legends like Common, Twista, Chance the Rapper, and Da Brat; newspaper and magazine articles featuring these artists.

Perhaps most importantly, it features a timeline detailing Chicago’s contributions to not only the genre, but to music in general. (Full disclosure, one of the writer’s articles is framed in the museum.)

Roberts and his team do something rarely seen this year during hip-hop’s 50th anniversary: the museum gives the city—its breakers, emcees, DJs, and graf writers—their flowers. After all, Chicago’s contributions to hip-hop are often reduced to passing mentions or a quick, backhanded acknowledgement of drill, a controversial subgenre now imitated by other cities and international artists.

The folks who fondly remember the South Side ’90s hip-hop scene are fiercely protective when preserving their history—so much so that many continue to keep their lived experiences in mind when contributing to their communities today.

Whether they’re advocating for the responsible consumption of marijuana, preserving local hip-hop heritage, or co-founding a youth organization that’s leading the conversation on self-reliance within intentionally divested communities, hip-hop remains front and center for the people who spoke to the Weekly.

Arianne Richards is the executive director of Chicago NORML, a marijuana advocacy organization, and a member of Euphonics, a South Side hip-hop collective that was well-known for its parties at Chicago venues. Later, she was instrumental in forming Euphonics’ all-girl offshoot, Euphoria.

“A lot of times, being a young girl in the culture could be challenging, you know? Just because it was almost like we were looked at as [if] we had to prove ourselves harder just because we were women,” said Richards. “One of the things that was birthed out of that was us forming the Euphoria crew.”

Having lived in Bronzeville and Beverly, Richards was one of the co-hosts of “Whatz Up Show,” a ’90s CAN TV call-in talk show where Euphonics/Euphoria members brazenly discussed the city’s subculture.

“Why do we feel like we have to answer to these guys all the time? [The guys] don’t put that same pressure on each other,” Richards said. “But now when I look back, I look at it as it was, a safe space for us as young women figuring ourselves out and who we were. [And] it’s funny because we were looked at as this subculture, and it’s interesting how it’s developed into something that is definitely not a subculture anymore. Hip-hop is embedded in everything now.”

Kofi Ademola, the cofounder of youth organization GoodKids MadCity, credits Chicago hip-hop for saving his life. Ademola says the genre pulled him out of tense situations in the streets and allowed him to build a community with the hip-hop scene.

This is top of mind when advising GKMC and the Peace Book, a public safety resource that sets up neighborhood-based peace commissions. The Peace Book also aims to assist community-based groups who will train young people to become peacekeepers, violence interrupters, mediators, and restorative justice practitioners.

“When I got introduced to hip-hop, it brought me a community and relationships with people who would otherwise have been my opps [opposition],” said Ademola, who is also an Euphonics member. “It taught us more of our similarities than differences…. It made us put a lot of our flags down to really build a community together.”

Related story

People like Richards, Roberts, and Ademola often give credit to community elders who provided spaces for youth like them to navigate the world.

Nancy Cobb, the mother of Euphonics member Krsna Golden, thought of her community organizing background when allowing her son and his friends to utilize the basement of her Washington Heights home—as long as Golden agreed to her strict terms (graduate from high school, get a job, pay rent, etc.) Virginia Cobb, Nancy’s mother and Golden’s grandmother, who bought the home in 1966, co-signed Euphonics’ use of the space.

The collective now had space to strategize, breakdance, and write raps, among other activites. “As they were creating Euphonics they were meeting at my house and Krsna was at that stage of wanting some independence, but he wasn’t grown; he’s still in high school. I said, ‘Well, here’s what you got to do,’” Cobb said. “I have an appreciation for the culture as it was a way to persuade not just the kids themselves, but the adult communities of parents to be involved and support these kids in their artistic endeavors.”

“The kids are going to run their world eventually, so let’s give them a good start. There were a couple of kids where hip-hop saved their lives, because they sort of went the other way; the gangs were recruiting them. I let [Euphonics members] stay in the basement. They always thought they were sneaking in or sneaking out, or staying late. I knew what was going on [laughs].”

Richards reflects on the significance of Cobb’s basement as a gathering and creative space. She passes down the lessons learned back then as she raises three daughters ages fifteen, ten and eight.

To some, saying hip-hop saves lives may sound corny. Others will say the genre is rife with violence, sexism, culture vultures, shattered dreams, and broken promises. However, many call bulls–t on any blanket statements—including Chicago’s erasure.

After all, several of our city’s community leaders found their footing in hip-hop: a genre that prefers honesty over perfection.

Evan F. Moore is an award-winning writer, author, and DePaul University journalism adjunct instructor. Evan is a third-generation South Shore homeowner.

O hip-hop está ficando esquecido, muito triste ver a história se acabando

Brilliant take on Chicago’s footprint in the annals of Hip Hop

I appreciate this article I truly stand firm and believe in the culture can make a difference in our society or society itself I believe that in Chicago we all deserve opportunity to grow to learn and to educate and to lead more articles like this need to be made about Chicago hip Hop for all of the states of America can learn about Chicago creativity and it’s rap scene. Thank you and ✌️