What happens when we do not learn from the past?

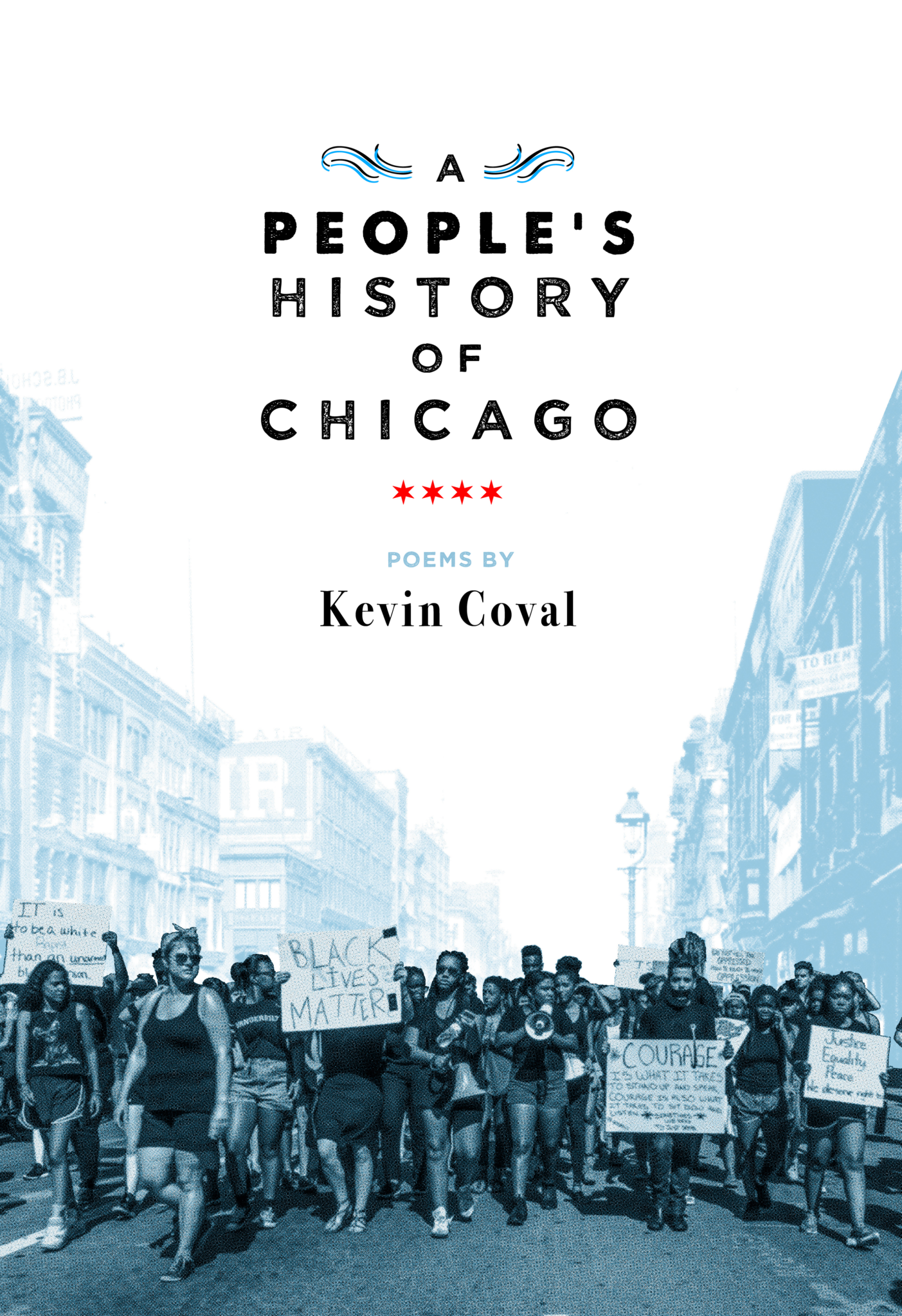

In the wake of the Department of Justice investigation of the Chicago Police Department, Kevin Coval’s honest look at the past in his new book of poems, A People’s History of Chicago, could be a reminder of how to move forward.

“I think that white people shy away from the reality of history,” Coval said when we discussed the DOJ Report and his book two days after the report was released. “But I think when we aspire toward justice and equity, that [to] claim where we’ve been and own it and apologize and do better….is how we ultimately strive toward a more equitable and just future.”

Coval’s book reflects this sentiment of reclamation, putting into verse over 525 years of Chicagoland’s existence in an effort, according to Coval, “to insist for a different kind of civic space and a different kind of civic narrative.” The collection of seventy-seven poems (one for each neighborhood in the city) begins before European arrival in North America and ends with the 180th anniversary of Chicago’s incorporation, on March 4, 2017. The book is slated to get its first public reading on that day.

Between these bookends, Coval seems to ask his readers what—if anything—has changed over the centuries. Though the poems are ordered chronologically, references to police violence, strained race relations, and an ever-culminating resistance appear cyclically throughout the poems. They suggest ways of seeing the present in the past as much as we see the past in the present. “Patronage,” dated February 29, 1992, demonstrates this well in the wake of the DOJ report: “when evidence of police torture / graced his [Richard M. Daley’s] desk in the early 80s / it was ignored. his ignorance made him / mayor.” The history that Coval constructs reminds, again and again, of a city that has yet to claim its past, fully and completely.

And for Coval, claiming the past does not—and should not—require any sort of embrace. It often requires the exact opposite, to stare unflinchingly at the “lakes polluted, the blood diseased, the people / rounded into prisons, reservations, Maywood.” To claim the city’s history is also to decapitalize the giants that have largely written the dominant narrative: the demotion of names like lasalle, richard m. daley, jane byrne, and barack obama to lowercase is a motif that Coval plays with throughout the course of the book. It’s another way that Coval picks and chooses his version of history, to instead memorialize figures like Ida B. Wells or Studs Terkel or Chief Keef.

But the collection is not merely a litany of historic crescendos. Another way to understand the collection of poems is as a meditation on Coval’s personal history and relationship with the city—or, at the very least, an open questioning of what it means to construct a history, and whom he can include in such a project. Many of the events and individuals he chooses to memorialize are already unquestionably seared into the city’s collective memory: the assassination of Fred Hampton; the death of Harold Washington; the election of Barack Obama. But others—small, introspective nods to his great-grandmother and grandfather, or to the housing development where his parents met—help carve out a small place for the personal and the individual, even in a project that bills itself as a collective history. Coval’s personal stake in these poems is actually subtler than the occasional invocation of his family members. “Don L. Lee Becomes Haki Madhubhuti,” for example, is a tribute not just to an acclaimed poet, but also someone whom Coval views as a longtime mentor. Allusions to his personal stake in the city remind us that Coval critiques Chicago not from a distance, but as a resident and a citizen, and as someone who hopes that reclamation can pave the way for change.

Coval hopes that his book can play its part: he plans to host 180 readings across all seventy-seven community areas in the coming year. Along the way, he says he will collect narratives and oral histories from audience members he meets to begin to construct what he calls “an ongoing oral poetic story of the city.”

“History is an essential component of movement making and building,” he told me.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.