People from the South Side have a certain kind of DIY attitude to them. Decades of expropriation have made it so that we have no other choice. This attitude rings through chants like “Whose Streets, Our Streets!” and “We Keep Us Safe!” and it animates the countless organizations working to rebuild and remake our communities. In his short film The Sanctuary, Katon Blackburn shows us his own vision for this DIY spirit: that on top of building our own communities, we can create our own fun, and that if we’re resourceful enough, we can do it in the very spaces that were taken from us.

It started with Seamoss, Katon’s first street-skate film shot on the South Side. Katon’s mom recognized the voice of a shouting bystander in the video and connected him with Katon. Turns out, he had access to Anthony Overton Elementary School, which was among the fifty schools Rahm Emanuel infamously closed in 2013.

Winter was approaching, and Katon lobbed a request to use the space as an indoor skate park. His wish was granted. “It all just happened so organically…We finally had a little place to skate over the winter, on the South Side of Chicago—which was like the biggest deal for me and him, because that’s something we’ve never ever had growing up as skaters,” Katon said.

What followed was The Sanctuary: a 35-minute chronicle of the winter spent skating in Overton back in 2020, with graffitied walls adding new character to the hallways, songs from classic artists like Maze and Alice Coltrane, and of course, tricks like ‘krook nollie heel outs’ and ‘faker flip switch mannys’.

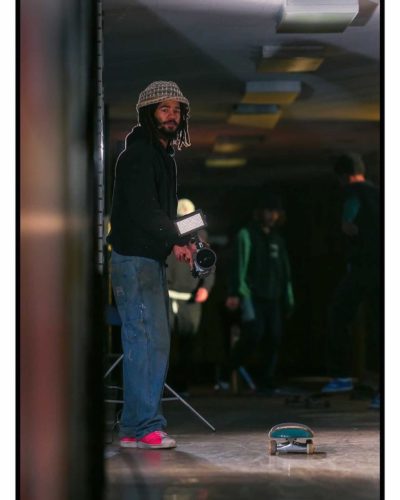

The life force of the film is carried by the fist bumps, the soothing sounds of trucks hitting cement floors, the pure joy for skateboarding evident on each face featured in the video, and the nostalgic grain of the Sony Digital Handycam and MK1 fisheye lens, reminiscent of something from MTV circa 2005.

The film opens with footage of Bronzeville and audio from news coverage of the school closures, followed by a clip of Eve Ewing dissecting inequities in the public education system across racial lines in this country. This combination of media sets the context for the set of the film: one of the schools that the district decided not to save.

In the winds of winter, Katon, Roland Wiley, and skaters from all over Chicagoland ventured to an abandoned school with no heat or running water to skate with one another. In the film, Katon asks them, “What do you love about skating?” Each answer revolves around skateboarding’s freeing qualities and its ability to bring people together, no matter their walk of life. A nation-builder in its own right.

Katon is no stranger to building communities. He is one of the founders of Natty Bwoy Bikes and Boards, a skateboard and bicycle repair shop that was housed at Boxville, a shipping container marketplace by the 51st Green Line station. When the weather’s nice, he teaches skateboarding lessons at Kenwood Park on Sundays to youth of all ages. The two ventures alone serve unique purposes—but together, they create an ecosystem, an entry point.

“When I was growing up as a kid on the South Side I felt like it was kind of hard to get into it,” Blackburn said. “So for kids who don’t have that access, I just want to make sure that there’s a space now on the South Side where, if you want to get into this thing, you can come and you can feel welcomed.”

The Weekly caught up with Katon to ask him more about his skate journey, how it led him to filming The Sanctuary, and what he hopes people take away from it.

Where in Chicago are you from? What are the spaces you frequented and how did you get into skateboarding?

I’m originally from the South Shore neighborhood of Chicago. I was born in my grandma’s house on 73rd and Constance. We lived there for a little and then when I was maybe like, around five or something, my mother bought a house at 81st and Euclid, and I spent ten years of my life there. How did I even get into skateboarding? I have two older brothers. And I just remember before I even started skating, we had scooters, like those Razor scooters. And riding around on them only was like, so fun for so long. So eventually, we started trying to do tricks on them and like, jump on them. And then I remember one day, my older brother Kahari brought home a skateboard. And I was just super enchanted and fascinated by it. So we ended up on a skateboard. My mom bought one for all of us. And in our backyard, my mom had this little court, like some cement laid down that we use as a basketball court—that’s where I kind of learned how to skateboard on those courts. And it was just like our flat ground area. And we would just build hella shit with like two-by-fours and sheets of plywood and bricks.

You were building stuff from an early age?

From an early age we were building our own little skate sets, and like our own types of obstacles to skate. And we would make little gaps and we would make ramps, we would make little rails—like the rails would be so sketchy. It would literally be like two bricks stacked on each other and then a two-by-four laid across some bricks. So the rail could fall at any moment, it wasn’t like drilled in or anything. We literally learned how to skate in that backyard.

Probably the most influential space after that backyard would be when we discovered 31st, the skate park over on the lake. Spent a lot of time up there. We kind of grew up as skaters up there. And going to 31st was when I had one of my first experiences seeing other skaters that looked like me. And one that I remember in particular is a big homie of mine—his name’s Billa and he actually has a clip in The Sanctuary. I probably first met him [at 31st] when I was like in second or third grade, and he had like the longest locs all the way down his back. He was always doing tricks on the manual pad. It definitely helped me envision or just made me feel like I could really be a part of this culture, this thing called skateboarding, because I saw myself represented so much in him.

Do you feel like skateboarding is unique in the ways it brings people together?

I wouldn’t say that it’s unique in that manner. I feel like sports in general kind of do that. But [this is] what I always say is kind of different about skateboarding: I do consider it a sport, but I also consider it an art form. I also consider it a lifestyle. A lot of people ask me what do I do? ‘Oh, what do you do? What do you do? What’s your job?’ And all the times I don’t have a job to tell people, I just say, ‘I’m a skateboarder.’ That is kind of how I identify myself.

One thing that I think is unique about skateboarding: with most other sports, you need someone else to do it with you. I mean, you can practice soccer on your own, you can practice basketball on your own. But, uh, to actually be good and understand how to play the game, you’re gonna have to eventually start playing with other people. And skateboarding is different in that manner. All you need to get better at skateboarding is you, yourself and that determination. You have to actually want to get on your board all the time.

And from the film you can see that it’s more of an individual pursuit in that way. Not all of you are doing the same tricks, you all have your own style.

Yeah. At the beginning of my part, I say this quote by Lance Mountain, who’s a skateboarder. ‘It’s not that you’re able to do it, but it is how you do it.’ And a huge thing just about skateboarding in general, it’s all about style. It’s all about how you see it. The course for the most part stayed the same throughout the video. But anytime I brought another person to the space, they would totally look at it differently.

Sometimes I compare skateboarding to cooking in the fact that like, you only have so many tricks or you only have so many things. I only have a tomato, a shallot and onion, and dry pasta. So like, what can I do with it? And what I think I can do with that tomato, onion, shallot and pasta might be totally different than what the next person thinks they could do with it.

Skateboarding is a super creative thing because everyone has a different brain. So I’m just going to look at the course differently. And we’re going to assess that course based on what it is that we’re capable of doing. So, yeah, that’s where you start to see the individuality of the art form.

What does it mean to transform a school that was closed into one where your community could come together?

It was a blessing and we were fortunate to be able to do it. And it was just sick that it became a place of education once again. This is the wintertime. This is a time where normally skaters, especially from the South Side of Chicago, wouldn’t be skating much. We would be losing tricks. So the fact that we were able to be in this space and cultivate it and create it, and continue to kind of progress in our own journeys on the board… it became a place of education, we would go there as if it was Skate High School.

There’s this one scene where we run into these kids on the street. Me and Roland, we see them outside the window and they had their skateboards, [so] we invite them into the school and we’re like, ‘Yo, like you guys skate? Come in here, blah, blah.’ They were super hyped. I ended up staying in touch with one of the kids and we made sure they were straight. I bought them a fresh pair of Vans and we would bring them decks and anything they needed in terms of skate supplies. And it was sick to just be able to do that because he literally stayed right down the street. He was living at his grandma’s house. So that would have been his neighboring school, had it still been open today. So the fact that he could go there those few times and actually learn something—it was pretty cool. It was like he was going to school just for skating.

Would you consider yourself an educator?

I would say that’s not far off. I mean, I’ve been giving skate lessons for like over a year now. So I mean, that’s the education in its own. And I mean, skating has made a huge impact on my life. It has made me more confident. It’s made me more fearless. It’s helped my social skills. It’s helped me understand and break down certain cultural barriers. I think skating is a huge educational tool and a huge tool that can be used to help motivate and teach kids things.

You can watch The Sanctuary here.

Malik is the housing editor for the Weekly. He last wrote a review of Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance.