Vida Cross’s Bronzeville at Night: 1949 is full of spells—spells to protect children, spells to blind ignorant sociologists, spells to aid in grieving and remembrance. The poet, professor, and third-generation Chicagoan’s debut poetry collection is a web of stories that, like spells, are small in scope and broad in impact.

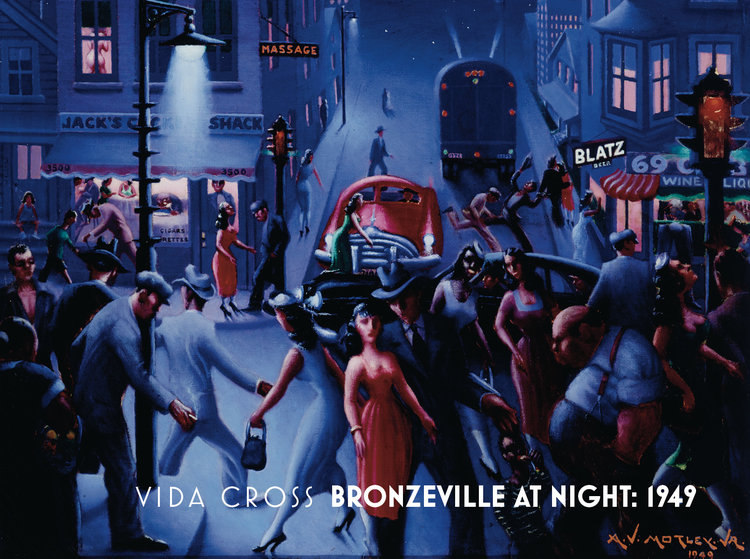

Cross’s stories move between living rooms, chicken shacks, and neighborhood churches, against the buzzing backdrop of the Great Migration and Harlem Renaissance. Her poetry is largely ekphrastic—inspired by visual art—and focused on the work of Black Chicago artist Archibald Motley. Motley’s bustling painting “Bronzeville at Night” serves as the collection’s titular inspiration, and this and many of his other pieces provide a basis for settings, characters, and tones.

Cross also cites the “poetic research” of Langston Hughes as a primary inspiration. In an interview with Awst Press, she described how Hughes centers his documentation of Black culture around blues music and blues humor. Like Motley and Hughes, Cross is a researcher as well as a poet, capturing a place in time and deftly weaving words with Black music and art. Her redux of Langston Hughes’ “Dream Boogie,” for instance, describes the Chicago “boogie-woogie” and its dancers with an improvisational, rhythmic cadence.

The people of Bronzeville and their idiosyncrasies and interactions drive the collection. We meet Bodacious, a bold, red-clad woman who lives in a greystone on St. Lawrence Avenue. We meet the witch doctor, who has no teeth but wears rose-scented cologne from the five-and-dime. We meet a drunken preacher and his wife, whose strained relationship breaks into blues melodies. Cross weaves despair and laughter through these characters’ stories, detailing sorrowful wakes in one stanza and pet chickens in the next. While these images seem disparate, their coexistence creates a bittersweet yet lighthearted tone—humor, in these stories, is a means of coping and community building.

Despite this, despair swells to the forefront of middle section “The Children / The Chitlins,” where the speaker explores her relationship with her two younger sisters, Marlene and Asunda. In these poems, the siblings learn to understand one another as they learn to accept death, loss, and their parents’ estrangement. In the Awst Press interview Cross explained that she wanted ‘The Children / The Chitlins” to emphasize the disproportionate impact of tragedy on children, who have to “be wise beyond their years” and “endure things that they should not have to.” “Asunda’s Story,” one of the section’s most subtle, chilling poems, describes the crossroads of trauma and innocence in the lines “I feel like climbing under the bed / leaving parts of myself standing / so’s I can ease-drop on what I have said.” How, if possible, can we prevent this dissociation? “Let child bathe in blackberries,” Cross urges. “Let child play in blackberries.”

Cross makes sure to address the ambivalent relationships that Bronzeville residents have with the place they inhabit. Some poems burst with fondness for the neighborhood while others express frustration with segregation and isolation, with “struggling to uproot / wanting to run.” Regardless, the South Side itself is an important character in the poet’s cast. The city juts into lonely moments and personal reflections, sometimes playfully, sometimes lyrically, but always sharply. In “Jitney on a Sunday Morning,” a church usher recalls one of the local preacher’s “drunken yarns” along the route of the King Drive bus. Announcements of “35th Street,” “43rd Street,” and finally, “47th Street” punctuate the yarn, a sad and surreal story of death, family, and memorial. Other poems equate urban noises with natural phenomena. “In city summers,” Cross begins in the titular poem “Bronzeville at Night,” “we wait for the breeze / from trains / rain / or slammed doors.”

Throughout the collection Cross positions observers as the observed and renders oppressors anonymous. In “The Witch Doctor,” Bronzeville residents curse and gawk at a “white social-science-social worker” studying the neighborhood. Later, in “A Story Told,” the quiltmaker omits the names of white townspeople from the tale of Leon, a Black man mistaken for a slave. The observed-observer dichotomy, however, also appears outside of discussions of institutional racism and provides insight into Cross’s authorial agency. In part two of “Bronzeville at Night,” “State Street,” the speaker watches Archibald Motley as he hovers under the blue lights of Jack’s Chicken Shack, sketching its patrons. She sits on the stoop, “hoping Mr. Mot would sketch [her] too.”

In Bronzeville at Night: 1949 Cross picks up the pen herself rather than waiting for Mr. Mot; she celebrates her artistic predecessors while building upon their work. The resulting sketch is an immersive and emotive portrait of a community—of its names, songs, and stories. Her words, like breezes from trains and rain and slammed doors, shake us into awareness of our surroundings.

Vida Cross, Bronzeville at Night: 1949. $16. Awst Press.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

I’ve enjoyed reading this book of poetry and I find that the reviewer spoke well to it’s nature and layers of the author’s life.

The well written review made me want to read this book of poetry; so, I have purchased a copy.