Moratoria on evictions put in place by local, state, and federal authorities in the early weeks of the pandemic recognized an obvious truth: amid a public health crisis, having stable housing is vital to protect people’s health.

Despite that, we’ve seen familiar stories play out in the last year, perpetuating the painful reality that many of Chicago’s enduring inequalities are founded upon one fundamental force: residential segregation. With Black and Latinx communities home to significant concentrations of essential workers, these communities also saw the greatest numbers of COVID infections and deaths.

But if eviction protections saved many from losing their homes due to loss of income, childcare needs, or from the fallout of a COVID-related illness or death, we may soon see more than 20,000 evictions in the month after the moratorium is lifted, according to predictions from the Lawyers’ Committee for Better Housing (LCBH). Although state-level rental assistance is expected to reach thousands of residents, housing insecurity goes deeper than the pandemic.

We need policies to do more than cover up wounds that were deepened but not created by the pandemic; we need them to secure housing as a fundamental right for all.

One such policy is Just Cause for Eviction, which our coalition, the Chicago Housing Justice League (CHJL), has been advocating for since 2019. [The Weekly previously covered the Just Cause ordinance in an op-ed by Bobby Vanecko in April 2020.] The policy currently governs over 10 million rental units nationwide, including four states and more than twenty cities, and in all federally-subsidized affordable housing units.

Just Cause’s fundamental principle is simple: renters deserve the right to remain stably housed. Today, renters who are current on rent and are good neighbors are vulnerable to sudden displacement, whether due to eviction, non-renewal, or lease termination. Before the pandemic, LCBH estimated that 10,000 Chicago households typically faced these outcomes each year, creating instability and lifelong harm, particularly for children. Despite the eviction moratoria, some landlords have filed eviction cases, and some have illegally locked their tenants out, during the pandemic. Unless Just Cause is passed, tenants will be at risk of these unscrupulous practices well after COVID-19 has subsided.

Just Cause ends the practice of no-fault, no-cause evictions by establishing seven exclusive just grounds for ending the landlord-tenant relationship. On the tenant side, nonpayment of rent, disruption to neighbors or damage of property, or a refusal to renew a lease under similar terms remain present. The bill also recognizes four landlord-side reasons for wanting a tenant moved out: desire to substantially rehabilitate a unit, to move in a qualified family member, to remove the unit from the market, or to convert it to a condo. If a tenant is not at fault, renters must then be given relocation funds that will ease their transition into other housing, a much-needed change that recognizes the devastating impact of sudden displacement.

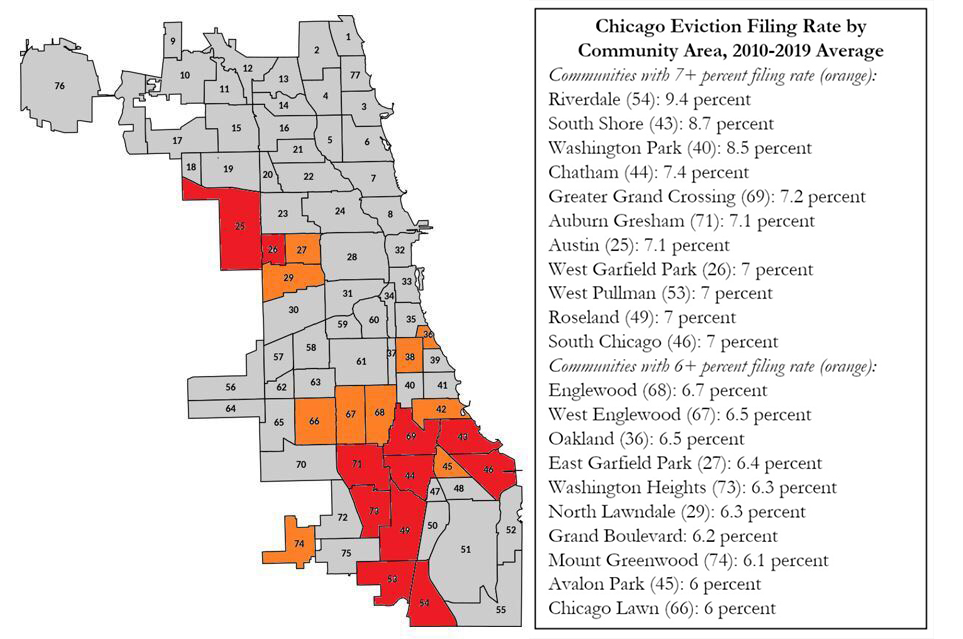

Examining a map of Chicago’s eviction filing rates over the last decade reveals a painful, unsurprising truth: each of the twenty-one community areas with average rates greater than six percent had a majority-Black population. The disproportionate toll of evictions falls in these communities, most acutely on Black women, who have previously been estimated to be about half of those who appear in eviction court.

While Just Cause cannot unsettle underlying issues like low wages, over-policing, and underfunded schools, it can protect renters, in part, from unscrupulous landlords like Pangea, responsible for thousands of Chicago evictions in the last decade. One of the most common reasons for no-fault eviction is as a form of retaliation against tenants demanding necessary repairs to their units. Rather than dealing with building code violations that cause harm to renters, particularly children and the elderly, those seeking repair are often met with an eviction notice instead.

This is exactly what happened to Sharon Norwood, an organizer with Working Family Solidarity, a CHJL coalition member. She had lived for eleven years in a rented house that had bad plumbing (which would sometimes cost her $1,000 in monthly water bills), and mold that threatened her family’s health. Norwood also ran a home childcare facility and had foster children, and when the state of Illinois told her the property needed repair, she was forced to invest her own money to deal with the issues when the landlord refused to repair.

After raising concerns, her landlord filed to evict her in early 2020, just before the pandemic. In court, Norwood struck a deal to move out without an eviction, leaving her savings drained. She was prevented from getting access to family photos and government documents when she was locked out by the landlord while moving.

“If Just Cause was the law, she wouldn’t have been able to retaliate against me,” Norwood said. “We don’t want to cause trouble, we’d rather stay where we’re at, because it’s hard to be uprooted from a place that you’ve been at for a long time.”

Norwood’s story is just one example of the urgency of Just Cause, reflecting the ongoing imbalance in landlord-tenant dynamics. Stable housing for renters should not come at the whim of a landlord who can remove them for no reason, especially when no-fault removals are often tied to retaliation, or to flip a building for higher rental incomes. Yet without Just Cause, this unconscionable outcome remains common for too many of Chicago’s 1.4 million renters.

The Urban Institute estimates that by 2030, Chicago’s Black population will decline to 665,000, almost half the city’s historic peak of 1.2 million. Chicago’s leaders have given Black residents ample reasons to leave, from shuttering schools and under-resourcing (and then demolishing) public housing to dealing with violence through more policing instead of funding mental health and other community resources. A right to stable housing is something else that many Black Chicagoans cannot take for granted, and countless displaced people are the victims of unfair rental policies that suggest their right to the city is less valued than others.

Until these families know that the basic security of continuous tenancy is present, how many others will leave our city, long after special COVID-19 protections delay the pain just a little while longer?

Annie Howard is the Equity and Operations Organizer for the Chicago Housing Justice League. This is their first piece for the Weekly.