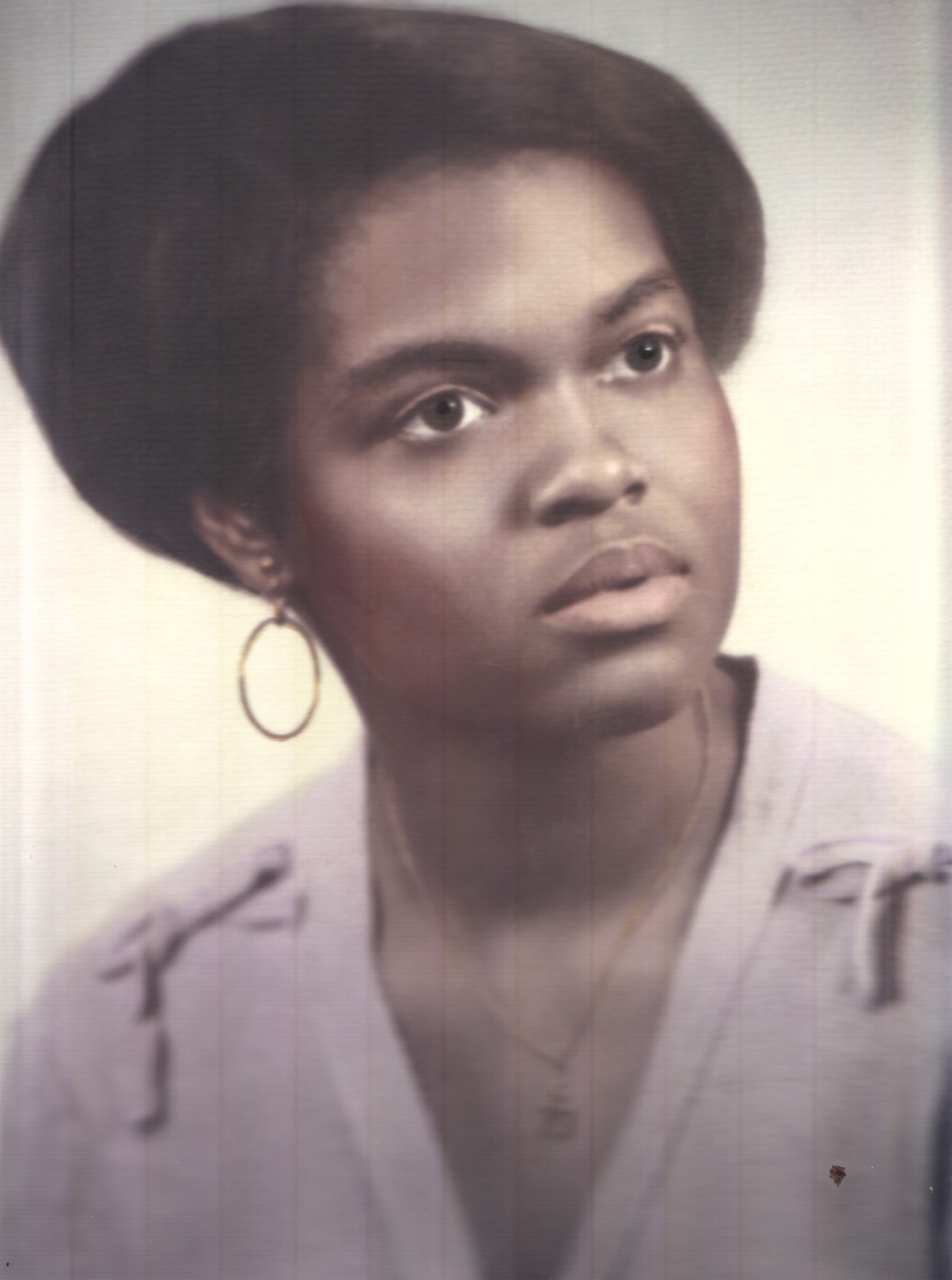

My first venture into the workforce in 1972 was as a secretary for the City of Chicago, Department of Water and Sewers. I was offered this job during my senior year at Jones, as all seniors had to work a half day. When I started working for the City, my father helped me in the only way he knew how. It was normally my mother to whom we went for advice, sometimes to just talk things out. But I remember before I started my job at City Hall he told me to say “yes ma’am” and “yes sir,” when I was addressing the white people downtown. When my father advised me to show deference to the white people with whom I would come into contact with at my first job, the first thing that he was referring to was that old Southern, colored idea of inferiority that he believed I should consider when dealing with white people. In that moment, it struck me that no matter how cute or smart I thought I was, wearing my nice little dresses and stockings and shoes, plopping on a nice hat and pulling on gloves, my father thought that I still had to make sure I kept my place and didn’t disrespect the white people downtown.

The comings and goings at City Hall were something to behold for a sixteen-year-old girl from the South Side. Powerbrokers would come through the hallways, dressed in nice suits, ties, leather loafers and pinky rings, while carrying leather briefcases. They would go for lunch at restaurants with such names as Mayor’s Row, Hinkey Dink’s Tavern and Counselor’s Row.

I was working at the City when the first Mayor Daley passed away in December 1976. Richard J. Daley had ruled the city for twenty-one years and afterward his body would lie in the hallways of the building that he had known so well. His son Richard M. Daley served as Chicago’s mayor from 1989 until 2011, when he decided not to run again. But before the son came into office, Chicago witnessed the election of its first African-American mayor, Harold “you want Harold, you got him” Washington. Washington ran a successful grassroots campaign and was adored by the masses. He was first elected in April 1983 and won re-election in 1987. Unfortunately, he died in office in November 1987. His personality was infectious and the city mourned his passing. It left many African Americans wondering just when we would see another black mayor. We weren’t even thinking at the time that we would see something more profound than another black mayor. We would live to see Obama elected to the highest office in our nation—not once, but two times.

Hanging out with my coworkers during this time meant discovering the upscale Marshall Field & Company (Macy’s), after I had been used to buying dresses and clothes at Lerner Shops and other stores in the downtown area. An older co-worker taught me about buying quality instead of quantity; therefore, Marshall Field’s seemed like the best choice. It wasn’t cheap and there weren’t many black salespeople working there at the time. As a matter of fact, at one time Field’s had a history of not being too welcoming to minorities, but I was too young to or get involved in political correctness by boycotting the store. I also learned about the Millionaire’s Club where you could get a good meal or a Sloe Gin Fizz or Tom Collins. We swore that they must have been mixing those drinks in the bathtub because you got free drinks with your meals. But they were not that strong. I ate my first lobster there, some time in my senior year of high school, and brought the shell home for a souvenir. I also discovered a club on West 87th Street, in Gresham that is still there now, Reeses. It wasn’t a matter of trying to be grown; it was more a situation where I was young and working with a slightly older crew, lunchtime and events right after work exposed me to what were then considered the finer or more exciting things in life.

There was a man who preached with a bullhorn and small amplifier. “You can’t get to Heaven smoking that reefer,” he admonished passersby. “And those of you who are living in sin won’t get to Heaven, either,” he proclaimed. I would see this man on the streets of downtown Chicago preaching the Gospel in the early 1970s and he is still there today. My buddies and I would also sometimes go to Flo’s, Beef and Brandy, and The Court to eat meals. All located downtown, these places welcomed the younger crowd, especially those who had money to pay for their meals.

It was so cool to be downtown working. It made me feel more mature and it certainly helped my parents since I had my own money. This first sadly opened my eyes to the discrimination that prevailed in Chicago. One of the disconcerting aspects about working for the City at that time was that many of my coworkers were from Bridgeport, a neighborhood made famous because the Daley family, which produced two Chicago mayors, came from that area. Another outstanding reference to Bridgeport came later in 1997 with the well-publicized beating of thirteen-year-old Lenard Clark, a black teen who lived in a nearby housing project, by a group of young white youth in an area bordering Bridgeport. He was just riding his bike in the neighborhood after playing basketball. He was targeted and kicked into a coma that resulted in brain damage.

Newspaper reports of the ensuing trial were graphic in nature and recounted sentiments from across the nation. An Associated Press article about the trial, written by Mike Robinson on April 19, 1998 and titled “Trial is putting racism in Chicago’s spotlight”, began this way:

When Lenard Clark was found crumpled and unconscious on a South Side street, the victim of a brutal beating, police had no doubt about the motive. The black thirteen-year-old had bicycled into a mostly white neighborhood one night last spring, and the color of his skin apparently sparked an attack so violent it touched a nerve across the nation. President Clinton asked Americans to pray for the youngster left comatose by a ‘savage and senseless assault driven by nothing but hate.’

Thirteen months later, the three young white men charged with trying to kill Lenard Clark are about to go on trial in a case that dramatically underscores the nation’s unresolved racial tensions. The scene of the beating, Armour Square, is at the edge of Bridgeport, a neighborhood of tidy blue collar homes that has given Chicago four mayors in fifty years—two of them named Daley.

When I was working and had associates from Bridgeport, that area was off-limits to blacks. A coworker having a baby shower was told by her landlord that he better not ever see her inviting niggers to her apartment or he would evict her. She was very apologetic. I just brushed it off, pretending or masking that I didn’t want to go anyway.

Originally published in Chapter Fifteen of Old School Adventures from Englewood—South Side of Chicago

Love the book. For those of you who have not purchased Elaine’s book, you must do so today. Congratulations E. I am proud of you! It is a privilege and and honor to say, “I Know Her”

Thanks, Val, I appreciate your support all the time. Yeah, what she said. Elaine