In early spring, three tenants in a Pilsen building got a notification that their property company was offering to renew their leases for the following year. The devil was in the details. The monthly rent for all three apartments would rise significantly—in one case by $725, a 55 percent increase.

The tenants had spent the better part of the past year organizing a tenants union and pressing the company, First Western Properties, for safer building conditions. They filed suit against the company for the rent hike, alleging that it was retaliation for their organizing. “We have done everything by the book, according to the RLTO (Residential Landlord and Tenant Ordinance), but we are still facing retaliatory rent increases,” said Tulsi McDaniels, one of the union’s members and one of the plaintiffs listed in the lawsuit, at a late May press conference outside the company’s West Loop office. (A lawyer for the company has said the new rent is “reasonable” and within the normal range of the rental market, and that the suggestion they were raised in response to organizing was “a bit ridiculous,” the Sun-Times reported.)

The lawsuit will take time to make its way through the courts; the first hearing isn’t until late September. But the First Western Tenant Union, a recent entrant into Chicago’s tenant organizing ecosystem, isn’t sitting around waiting for a judge’s ruling. Members are still canvassing and helping neighbors navigate the legal framework that dictates what tenants can do, what they can’t, when tenants can withhold rent for a lack of repairs, and how much is reasonable to withhold, McDaniels and co-organizers Cristina Miranda and Alex Wirt told the Weekly in an interview. Then the union will look to strengthen ties with other tenant unions based in other parts of the city.

The pandemic, its aftermath, and the growing crisis of affordability in Chicago have propelled a new surge of tenant organizing. At least a half-dozen unions, including First Western Tenant Union, have cropped up across the city in the last several years in response to evictions and poor or unsafe housing conditions. As they accomplish their primary goals—helping themselves and their neighbors through crisis—many are sticking around. Some are going nationwide: South Shore-based grassroots organization Not Me We recently announced it is joining a cohort of tenants unions from across the country to start a federation that will “bargain for tenant protections” and ultimately “guarantee housing as a public good.”

First Western Tenant Union

It’s crazy how quickly things got fixed in one year of us coming together, talking to our neighbors. It’s not hard to talk to your neighbors, especially when you’re talking about your landlord, who you’re all paying money to. If you’re in a situation where they’re not taking care of the building, you’re probably more likely to have a connection about this. So it’s really easy to talk to your neighbor, and then you actually see results because you’re acting collectively.

In our initial tenant meetings, we would talk about the issues that we wanted fixed. We included this in [our union] demand letter. We would meet on an as-needed basis. After that, we decided we wanted to start withholding [a small portion of our rent]. So we would discuss how we would withhold, and we would, you know, not have a formal vote, but essentially decide collectively on what our withholding percentages would be on certain issues. And we would do this for basically six months, meeting before we would send letters on certain issues.

We’ve done majority rules for a lot of our decisions. If anyone is feeling hesitant about something, we’ll talk it over and make the best decision that benefits everyone. It’s been really easy going. It has not been difficult to make decisions or or get things done.

With a lot of tenant unions starting out, you want to deal with your immediate needs before you can get to the rest of the stuff. And now we would like to build our base a little bit and obviously organize across other First Western buildings, and then organize across different organizations, working closer with [other tenant groups in the city], and then working with Just Cause [Chicago] and Lift the Ban. So we want to get these larger pieces of legislation passed as well, and be a tool for them to use.

The challenge we probably face the most is having consistently engaged tenants in other buildings. There’s an extremely high turnover rate with tenants. People are constantly cycling in and out of these apartments. We had a very successful canvassing campaign, but the people we were most engaged with, one was booted out of their apartment in May for no reason, and other tenants just moved out.

There’s a lot of inter-organization information sharing. We got a lot of information from NSRA [North Spaulding Renters Association, now known as All-Chicago Tenant Alliance, or ACTA] and learned our rights through MTO [Metropolitan Tenants Organization]. NSRA already had a monthly newsletter, or a bi-monthly newsletter letter, and some how-to guide books and stuff like that. Some of it is grassroots writing that we’re using. A lot of [tenant unions] have actually made their own material, like pamphlets and just like written material that has really helped us out. CUT [Chicago Union of Tenants] has already made a tenants rights handbook.

What’s scary is that Bring Chicago Home didn’t pass. I think people are even more angry and upset. And the Supreme Court makes homelessness essentially…I mean, they’re criminalizing it, right? So while we’re trying to move forward, there’s signs of things moving backward. But that’s not going to stop us.

What keeps us going would probably be small wins. This building that’s a couple blocks away from our building, their mailbox was entirely busted. They didn’t have access to their mail until we helped them fill out a withholding letter and they literally responded immediately to them. There was some mold in the basement. They painted over the mold, but they fixed the mailbox.

All-Chicago Tenant Alliance (formerly North Spaulding Renters Association)

There’s a few different legal campaigns going on right now. Some people are campaigning for rent control [and] Just Cause for Eviction. It would be nice to see both of those happen. But we also have experience with the existing tenant laws and that makes us skeptical. A Just Cause Eviction law without rent control lets landlords hike the rents; the other way around, they can just do weird evictions to get tenants out.

A lot of these laws that are meant to give rights to tenants, [but] they ended up sort of making it so that tenants have to go through the court system in order to do anything at all. We’ve had a heat case in the courts. And it still hasn’t been resolved, from two winters ago. And in the meantime, every tenant involved was pushed out of the building.

What we find is that landlords have a much more robust system of keeping track of everything, all their communications, because it’s their job. And that’s just the first inequality between tenants and landlords when it comes to the courts. Once they get into the court, the landlords typically have high-powered expensive lawyers, tenants have basically whatever [we can find].

We think that tenants across the city ideally would realize this, build organizations that are able to take control of the little bit of leverage that they do have, and really hold the landlords to it. In the 60s and 70s, there were activist lawyers who were willing to go to the courts with the intent of changing the law. But that’s secondary to tenants taking ownership of their building, being ready to rent strike, being ready to talk to their neighbors, being ready to do what they can to get changes.

We have three channels of reaching people this summer. One of them is the People’s Cooling Army [editor’s note: this is an ACTA initiative through which members source and distribute free air conditioners to West Side tenants for summer use.] The other one is doing our street team and tabling, which is just like running around and setting up and going into buildings. The other one is what we call “social investigation”—we go and meet tenants at laundromats.

Tenant organizing is basically the Wild West. There’s no formal union structures, there’s no agreements between tenants and landlords the way there is between labor and companies. This is what makes it very difficult, but at the same time, a place where a lot of creativity is possible, and different forms of experimentation are possible.

When it first started, there wasn’t very much structure. We sort of built a formal structure from our work that we were doing. We like to undertake structural processes as something where we experiment a little bit, and then we look at what has been working and formalize that—instead of immediately sitting down and cutting out like ten ground rules or whatever.

From that, we arrived at what might historically be called a cadre organization, where there’s an interior group that takes most of the work and responsibility. And then there’s a broader group that we pull in for smaller things based on their willingness. We formalized some ways of doing democratic votes. This structure remedies the [issue] that people have all different levels of involvement. We think that that keeps us going long-term. We have very committed people and they have responsibilities, and then other people can come and go as they please.

Our core has been kicked out of buildings and moved around and everything. In a lot of other unions this would typically cause it to dissolve, because it would seem that the point of the meeting was to improve the building conditions. And we see that as part of what we do. But we’re committed to a much larger tenant union as a part of a political project.

We can take seriously the idea that a union is a place where we can become new types of people and really address the maladies that we feel we are experiencing in society.

East Lake Tenants Union

We started in 2021. East Lake Tenants Union is for tenants residing in East Lake [buildings], past and current tenants. The majority of [East Lake’s] portfolio is low-income housing. And that is our audience. We organize them, educate them on their rights, try to change their mindset about being fearful of sticking up for themselves, and then mobilize them to action. And the end of what we’re trying to do is tenant ownership of these buildings.

We also have the Ella Flagg Tenants Union [editor’s note: a tenant union that is part of East Lake Tenant Union at a senior building that is owned by the Chicago Housing Authority and managed by East Lake Management].

So we have a meeting every month where we talk about things that we want to do. At the beginning of the year, we set a plan in place that we follow. And sometimes people come in and think, “Oh, we’re just here as a savior.” We are not—we are each other’s neighbors, friends, lovers, you know, everything. We come together as members. We’re membership driven. So the members are with it, we’re with it. If the members are not with it, we’re not with it. And that’s how we move.

Conditions, issues, that’s number one. And of course, retaliation and stuff. But it all stems from conditions. People are living in horrible, deplorable conditions: no hot water, mold, mildew, black mold, pest control, rats, roaches, broken ceilings. [Broken] elevators are a big thing.

Okay, you have a landlord, a property manager, she has an attitude or whatever. But you might put that aside if your elevator is working, if you don’t have rats and roaches.

[What would you say to people who are having issues in their building or thinking about starting a tenants union?]

I would say being resilient, knowing your audience, knowing what your audience likes, what your audience doesn’t like. I had the grocery giveaway at that building I used to live in, my neighbors love to party. Always sat out on the front lawn. So what did we do? We had our giveaway on the front lawn. Had some music. We brought people out.

I have this marketing mindset. They say you’re supposed to know your audience. If you say, “Oh, everyone’s my audience,” you have no audience. We know our base, so we have to be able to market to them. Yes, it’s challenging. We’re dealing with decades of neglect, decades of negligence, racism, all this stuff. So it’s going to take a little minute, but it can be done.

Seeing the community engagement, which is really important, seeing other tenants sharing their stories and sticking up for themselves, really overshadows the “I’m gonna get evicted” mindset that tenants have.

Ella Flagg Tenants Union finally got some good work with laundry machines. My seniors were out there in the snow, traveling blocks and blocks to do laundry so they don’t have to worry about that anymore.

Two days ago, I got a call from a woman, she was like, “Is this the tenants union?” I was like, “Yeah.” She was like, “Well, I live at such and such,” and I’m like, “The address is not in Chicago, where are you located?” She said, “I’m in Denver … my girlfriend gave me your information.” So that made me think about our reach.

The partnership and collaboration is really important. Yes, what we do is so hard, so we have to be able to be in community with one another, because there are folks who’ve been doing this for decades. I want to give a big shout out to folks that we’ve worked with, Northside Action for Justice, Alliance of the Southeast, Altgeld-Murray Homes Alumni Association, Uptown People’s Law Center.

I hope to see more tenants in control, and that is something that we’re doing right now. Next month, we will be hosting a community land trust training, also open to the public, about how to create a community land trust—because again, our overall end goal is to be in control and to be permanent people in the neighborhoods in which we are in.

Autonomous Tenants Union

ATU started in 2016. Many of the cofounders—it was eight of us, and more than half [of us] had already experienced an eviction, a mass eviction. We worked together at a community center in Albany Park. And when we left the community center, when we created ATU, we wanted to escape the nonprofit industrial complex. We wanted to not have staff, but to really create an organization that [builds] capacity by developing directly impacted tenants that were facing eviction.

When a new owner comes in and evicts everybody at the same time, that creates many crises. Not just for the individuals being evicted, but then it also saturates the amount of units that might be available in a specific area, because then you’re having thirty families that are having to move out. All of them want to stay within the community, because they have their kids in school, they have their grocery store, they have the networks in those communities, and ultimately having to relocate somewhere else, not only is costly, but it can also have other impacts, mentally.

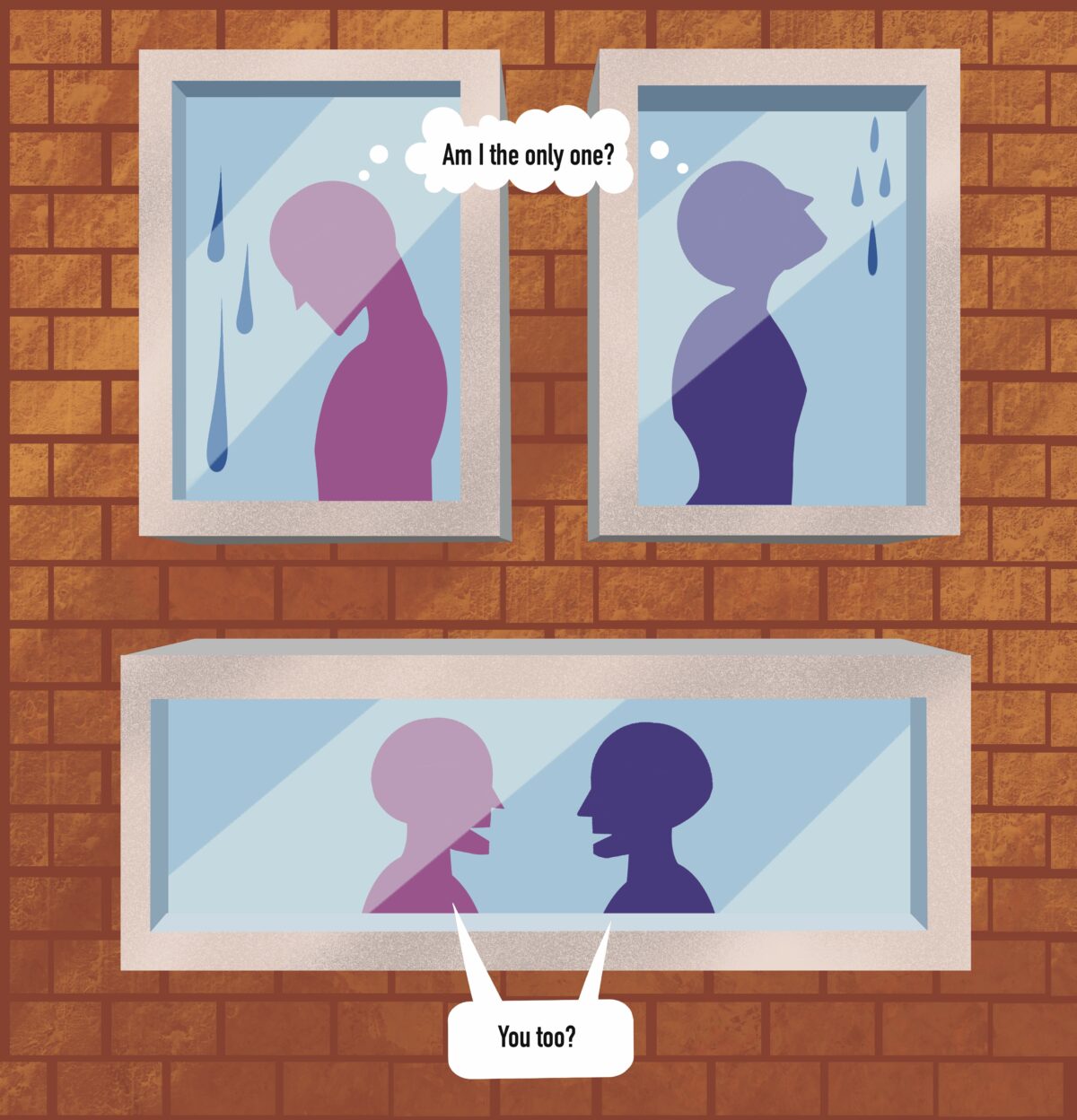

The main practice that we bring as ATU around making people understand the power of collectivity, or like working collectively and collaboratively with each other. And the tactic is to create a union…in order for them to feel like they’re not coming to the owner by themselves. Many times, it doesn’t work to go by as an individual to request condition repairs or cancellation of an eviction, but together, there’s a lot more power.

It is much more difficult than just forming the union in order for people to actually believe in collective power, especially when landlords tend to want to divide them.

The asamblea, that is our community assembly. That’s where all ATU members are expected to attend once a month right now. That’s also the space for like, if people know somebody that is going through an eviction, they can actually invite them there, and we can talk about what referrals, what support they need, resources that we have to offer collectively. Other members, especially tenants [who] have been [in] an eviction before, they can kind of sympathize with the individual and make sure that they get this fear out of the way which all of us, or ATU, has known.

We’re still volunteers. We have a very minimal budget that allows us to have money for direct action, for events.

We don’t have attorneys, we don’t have all those big resources that people sometimes are looking for. But we can offer something that we believe almost nobody else is offering, right? Like, the sense of self-determination, not just around housing, but in general, around other aspects of their lives. There are solutions that we can employ collectively, but we have to do it together, right?

Many of the people [we work with] end up leaving, sometimes months after they were supposed to—and those months were won because of the organizing that they did, or they got some kind of settlement from the owner. And so they take that settlement and they relocate somewhere else. The development of the skill set that we do for them, such as how to talk to the media, how to know your rights as a tenant—all of that, in a way, is great, because people are still taking the collective knowledge to their new communities or new neighborhoods, and a lot of the referrals that we get now after eight years, is really word of mouth. People talk about us, and they refer people to us…So we’re always trying to form a base and we see that as a creation of our power.

Emeline Posner is an independent journalist whose recent reporting can be found in the Weekly, the Investigative Project on Race and Equity, Illinois Answers Project, the Reader and elsewhere.