On August 5, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers raided a gas station on Belmont and Milwaukee Avenues that has long been a hiring site for day laborers (jornaleros) in Chicago. A group of workers—most of whom specialize in construction and landscaping—gathered that morning, as they do every day. They waited for employers who regularly come by to make job offers and negotiate a pay rate. The workers who frequent this particular site in Albany Park are black, Polish, Eastern European, Latinx. Some are immigrants, and some are not.

Analía Rodríguez—Executive Director of Latino Union, the only organization in Chicago that visits corner hiring sites to educate and organize workers—is still working to piece together the events of that day. According to witnesses who spoke with Latino Union and the workers themselves, two ICE officers who did not immediately identify themselves as ICE pulled up in an unmarked car and asked everyone present for their papers and fingerprints, using a mobile fingerprint scanner.

“The ICE truck really just came straight to that corner, that space where the Latino men were standing,” said Rodriguez. “They’re like, ‘Show us your papers.’ They fingerprinted them and grabbed [them] by the arm.”

Three workers were detained, handcuffed, and taken into ICE’s custody at Broadview Detention Center, west of Oak Park. “The workers didn’t know who [the officers] were—they could be police, they could be ICE,” Rodríguez said. “They did not find out they were ICE until they were in the detention center.”

Of the three workers taken to Broadview that day, one had temporary protective status (protection from deportation) and was let go after seventy-one hours of detention over the weekend. The second was also let go for unknown or unclear reasons. The third was released on bail, after Latino Union and other community partners helped him get a pro bono lawyer from the Community Activism Law Alliance. He has a court date in March.

Rodríguez has big questions about the legality of the August 5 raid and how it was conducted. Latino Union has filed a complaint with the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties. Who ordered this raid in the first place? Is there a Fourth Amendment argument against those mobile fingerprint scanners? Was there potentially any collaboration between ICE and the Chicago Police Department (CPD)?

How did this happen in Chicago?

Chicago is often referred to as a sanctuary city, a city that protects immigrants. But as the August 5 raid showed, the specific parameters of those protections matter a great deal. Chicago protects immigrants through city ordinance, through CPD directives, and through public services. The primary mode of this protection is “non-cooperation”: the City of Chicago and its departments will not cooperate with federal authorities to arrest, detain, or deport undocumented residents. This is what the Welcoming City Ordinance ensures. But many in Chicago are demanding more.

On January 14, a week ahead of the inauguration, around a thousand people gathered at the Chicago Teachers Union to unveil a “Platform of Resistance, Unity, and Respect.” Community leaders from across Illinois stood together reciting chants and holding signs: El pueblo unido jamás será vencido. No Muslim Registry. $15 and a Union.

“We need to stop criminalizing our communities and our cities,” declared the two emcees, Maleeha Chughtai of Asian Americans Advancing Justice Chicago and Araida Palacios of SEIU Healthcare Illinois-Indiana, who led the entire program in alternating English and Spanish.

The Platform of Resistance, Unity, and Respect, released by the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR) and endorsed by dozens of partner organizations, unfolded throughout the morning as speakers came up to the stage to give testimony. Students and teachers, union workers and organizers, members of the immigrant community and those with refugee status all spoke out that day. Each speaker related a personal experience with the immigration enforcement system, and called the crowd to action around the issue.

The speakers put forth a very clear set of policy demands, directed specifically at Governor Bruce Rauner and the other local, state, and federal elected officials who have yet to take action or even speak up to affirm the rights of immigrants and refugees since the November election. Only a few elected representatives were present that day, including U.S. Senator Dick Durbin, State Representative Will Guzzardi, and Cook County Commissioner Jesus “Chuy” Garcia.

Absent from the proceedings on January 14, both in physical form and in mention, was Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who has thus far been vocal in support of Chicago’s immigrants. Emanuel stated in mid-November that “Chicago has in the past been a sanctuary city [and] it always will be a sanctuary city.” In addition to ushering through public funds to support legal defense for immigrants, he has since the election called on Rauner to back Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance.

These displays of support in rhetoric and in much-needed funding are welcome to groups like ICIRR. But the mayor’s record on immigration (both recent and not so recent) deserves a closer look.

On December 7, Rahm Emanuel sat down with then-president-elect Donald Trump, presumably looked him in the eye, and delivered a letter signed by seventeen other municipal leaders. The letter asked the incoming administration to recognize and preserve Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which grants temporary lawful residency and work permits to young people who immigrated to the United States as children and meet a certain set of requirements. Established by the Obama administration in 2012 through executive action, the program was born out of failed congressional efforts to pass the DREAM Act, and was the product of years of organizing and political agitation on the part of immigrant communities. Tens of thousands of young people in Illinois have become “DACA-mented” over the past four years.

In the letter to Trump, Emanuel and the other signatories make the compelling point that “DACA is good for our nation’s economy.” What’s more, the letter says, “Ensuring DREAMers can continue to live and work in their communities without fear of deportation is the foundation of sound, responsible immigration policy.” The mayor also reportedly relayed a firm message to Trump that Sanctuary City policies would remain in place. Emanuel told the Tribune, “I talked about how all mayors and all cities that are sanctuary cities will stand by that principle.”

Out of all the mayors who could have delivered this message to Trump, it’s somewhat surprising that Emanuel was the one to take the meeting at Trump Tower and make the plea for the bare minimum of respect for young immigrants and their communities. As an advisor to the Clinton administration, Emanuel recommended that President Bill Clinton enact a series of extreme and aggressive measures on immigration enforcement: a month-long moratorium on naturalization, heightened border security and surveillance, an expansion of the National Guard’s role in policing the border. In a memo to Clinton, Emanuel notoriously wrote, “You will need such steps to get ahead of a bad story.”

This memo, written in 1996, coincided with the passage of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act. To its many critics over the years—including the thirty-two members of the House of Representatives who signed a resolution condemning the law in April of last year—the act was anything but “sound, responsible immigration policy.” Making it easier for the authorities to fast-track deportations and harder for immigrants to attain legal status, the 1996 law laid the foundation for the Obama-era deportation machine.

This is the immigration legacy that Emanuel brought back with him to Chicago. When the emcees at ICIRR’s January 14 rally called out, “We need to stop criminalizing our communities and our cities,” and demanded that Rauner stand up to protect immigrants, they were referring to an ongoing process that began with the Clinton administration, continued with Bush-era encroachments on civil liberties, and peaked with over two million deportations under President Barack Obama.

Trump himself has promised to deport two to three million people upon taking office. (He has also signaled that he would get rid of DACA.) According to the Department of Homeland Security’s own estimates and other independent research, there simply are not two or three million people in this country with serious criminal records who currently fall under the criteria for removal.

“One of the things that we are very concerned about, and this is an ongoing thing, is this criminalization of immigration and the movement of people,” says Mark Fleming, National Litigation Coordinator at the National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC). Speaking on the Trump administration’s deportation plans, he said, “How do you reach the two to three million? You morph and you fudge and you transform people into criminals who are not.” That means people with decades-old moving violations or shoplifting arrests—nonviolent offenses that can qualify as a felony (or a serious misdemeanor) depending on where you live. That also means people with prior deportations and reentry offenses.

And for all of Emanuel’s rhetoric around continuing to protect immigrants, these new targets of the Trump administration may not be protected here: even though Chicago is a sanctuary city, the Welcoming City Ordinance in its current form does not guarantee safety for all Chicagoans.

Predating even the Clinton years, Chicago had some kind of welcoming policy in place towards immigrants. Senior Policy Counsel at ICIRR Fred Tsao explains that Chicago has had a sort of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy concerning immigration status, dating back to Harold Washington’s administration in 1985. City departments, including CPD, were forbidden from asking about immigration status or conditioning receipt of public services or benefits on immigration status.

After Mayor Washington, Mayors Sawyer and Daley reaffirmed the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” version of Chicago’s attitude toward immigration. Daley and City Council wrote it into ordinance in 2006. In 2012 Rahm Emanuel and City Council passed the current Welcoming City Ordinance, Chapter 2-173 of the Chicago Code. Amended a few times since, the Ordinance now expressly prohibits threats made by police officers and other city agents based on immigration status or national origin, as well as most instances of collaboration between U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and city agencies.

But Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance also contains four carve-outs or exceptions that the Cook County companion ordinance (widely considered to be one of the more protective sanctuary ordinances in the country) does not. ICE and CPD can collaborate, share information, and conduct joint operations under four key circumstances of Chicago’s city ordinance: when someone is currently being prosecuted for a felony (a circumstance that ordinarily should not give rise to an arrest), has an outstanding criminal warrant, has a prior felony conviction, or is in the Chicago Gang Database. By contrast, the Cook County Sheriff will only communicate with ICE if given a signed criminal warrant.

Taken individually, these four carve-outs in Chicago’s ordinance are a tangle of legal and policy problems. But they often get tacked on the end of cities’ Welcoming Ordinances as a concession to federal deportation policy.

Many of these ordinances, including Chicago’s, passed in response to the federal Secure Communities program. Secure Communities was an initiative by ICE and the Department of Homeland Security—lauded by Trump, and consistently carried out under Obama—under which federal authorities had access to fingerprints that municipal police departments were routinely sending to the FBI. Federal agents could compare that local data to immigration databases in order to identify people who were in local police custody. ICE would then request that those individuals be held by the county jails and police departments past the time they would ordinarily be released. This request is called a detainer.

“[This practice] is, by the way, unconstitutional,” says Tsao. “So Cook County basically said, ‘Well, ICE, you can send whatever requests you want to, we’re not going obey them.’” Chicago said the same, with the exception of the aforementioned carve-outs.

The Supreme Court has not issued any final decision on the constitutionality of immigration detainers. But an October 2016 federal court order, which arose from a class-action lawsuit co-counseled by Fleming and NIJC, deemed them, at the very least, unlawful. A detainer is not a warrant, nor is it an order signed by a judge—it’s a request for an unlawful arrest. Fleming estimated that there are 31,000 of these unlawful detainers outstanding in the Midwest.

“I don’t think people appreciate how much the last decade is unlike any other period for immigration enforcement,” Fleming said. Through Secure Communities and its successor, the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP), ICE has “co-opted and coerced local law enforcement to be front line immigration officers,” he said.

In 2014, Obama axed Secure Communities through an executive order. PEP took its place. PEP relies less on detainers—ICE now encourages local police to notify them when people with felony convictions, three misdemeanors, or one significant misdemeanor (as well as people on a gang database) are being released, rather than extending their custody. Federal enforcement priorities line up very closely with the four carve-outs in Chicago’s ordinance.

“They rebranded it,” Fleming says of PEP. “It’s Secure Communities Lite.”

Tsao drew similar conclusions: “PEP is still in place and will probably remain in place, and possibly even jacked up further by the new administration,” he said. “They’ll find some way to dragoon local law enforcement into cooperation or collaboration with ICE.”

Between PEP and Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance carve-outs, both federal and local policies leave a lot of room for serious error—and for raids like the one on August 5. Analía Rodríguez has serious concerns about all aspects of how this raid was conducted, particularly on the legality of the mobile fingerprint scanners used by ICE—Fourth Amendment concerns.

“This is a very, very dangerous situation,” she said. “You may just find yourself just hanging outside of the park, outside your house with your family members, and ICE can just fingerprint you. Not looking for specific people, just fingerprinting everyone.”

Rodríguez emphasized that corner hiring sites are established places of work. Some have been around for twenty years. “People should know about it and this tradition,” she said. “We still don’t know about this specific raid…but the police also surveil this corner hiring spot. Patrol cars will stand there all morning, sometimes the police car will just pull up and keep harassing workers there throughout the day.”

Rodríguez knows that CPD knows where traditional corner hiring sites are. “They know there’s Latino men there,” she said, “and a good possibility there will be immigrants there. The question is: Is there collaboration?”

Rodríguez also knows that ICE has tried to justify their detention of the three workers by citing the fourth carve-out in the Welcoming City Ordinance: the gang database. Local police may share information or conduct joint operations with ICE if someone is identified as a known gang member on the CPD’s “gang database.” However, the CPD gang database is notoriously classified; it’s nearly impossible to find out who’s on it, how they got on it, and how they can get off. Things as arbitrary as “wearing red” could be enough to land people on the database.

Rodrigo Anzures, who works with the undocumented-led Organized Communities Against Deportations (OCAD), shares Rodríguez’s concerns about the August 5 raid. Through the Community Activism Law Alliance, Anzures is familiar with the particulars of the case and how the third worker ended up in ongoing proceedings. “If you look at his profile in the gang database, there is zero justification,” he said. “There’s places where you can put where they frequent, who they associate with, like all this information about why they’re in the gang database. And all those fields were blank. He’s just in the gang database.”

OCAD works on individual cases like this one, often in partnership with groups like Latino Union, and always with a community organizing model. Rallying support from friends and neighbors—encouraging people to show up at someone’s court date or make calls to the ICE field office—can mean the difference between a person going through full deportation proceedings or returning home to their family.

“We understand that the majority of our cases are won because we have the community organizing aspect,” says Anzures. “So just having [legal] representation isn’t enough, because I don’t think anyone will argue that if there’s a community organizing aspect to a case, [it] has a better shot of winning.” He added: “But then also, you need community organizing to change the laws that are in place.”

In describing the kind of policy work that OCAD does, both independently and as part of the broader Chicago Municipal Immigration Policy Working Group (which also includes ICIRR, NIJC, and Latino Union), Anzures stressed that the mayor and City Council can always do more, even with the threats coming from Trump and his administration to pull some or all federal funding for Sanctuary Cities.

“Even if [the City does] not want to move forward with getting rid of the carve-outs, there are more services they can provide,” Anzures said. “And there’s more that they have control over locally that they can do for immigrants in Chicago. Scrubbing the gang database is not going to affect their federal funding.”

OCAD has many of the same goals as the larger Working Group: getting rid of the four carve-outs in the Welcoming City Ordinance, limiting the sharing of sensitive information and data within the forthcoming municipal ID system, and designating public buildings as sanctuary spaces.

“[But] I think OCAD as an organization is willing to go much further than that,” Anzures added. “And I think we will in 2017. I think a big thing will be around criminalization, because we do work closely with a lot of Black Lives Matter groups, namely BYP100.”

It’s difficult to argue that Chicago police officers routinely driving by the corner of Belmont and Milwaukee, ordering workers to disperse, is making the community more secure. It is a symptom of over-policing. It is a tactic that signals to the jornaleros who gather there for work every day that they are being watched—by CPD at least, and in collaboration with ICE potentially.

But even on its own, ICE relies on public institutions, public databases, and public trust in the criminal justice system. Going over all the ways ICE conducts operations in Chicago, Mark Fleming explained that “ICE will troll public databases, for example, when someone has a bond hearing in traffic court. They will look for names that they…I mean, I don’t know how they do it, but from the description I’ve seen in documents, it sounds like they racially profile.” ICE officers will run searches on individual names and go from there, stopping someone as they go for a bond hearing in traffic court, outside their home, or at the corner where they look for work.

Fleming continued, “And to be honest when thinking about a Trump administration, I wouldn’t be surprised in a locality like Chicago, that they would try to have a high-profile raid sort of thing. It’s a very effective way to scare the hell out of a lot of people.”

After the first few days of the Trump administration, immigrants and advocates are still waiting to see if Trump will deliver on the many promises he has made: eliminating DACA, defunding sanctuary cities, restoring Secure Communities, restricting refugees.

But everyone has an idea of where things could be headed. The Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), the union that represents law enforcement officers in the United States, released a memo in December about the Trump administration’s first one hundred days. A disclaimer at the bottom noted that the memo “does not represent the FOP’s agenda…It is an advisory to our members as to what may happen when the new Administration takes over.”

In any case, almost half—eight out of eighteen—of the policy items listed in the FOP’s memo are directly related to immigration enforcement. The memo lists things like revoking federal funds to sanctuary cities, ending DACA, an expansion of the 287(g) program that essentially officially deputizes local law enforcement as frontline immigration officers, a reversal of the “Bush-era ban on racial profiling by all or some Federal agencies,” and use of mandatory minimum sentences for immigrants with prior deportations.

Chicago’s FOP Lodge 7 did not respond to requests for comment on the national FOP’s memo.

As these exceptionally aggressive shifts in federal policy loom closer every day, Anzures and OCAD want to see some equally aggressive changes happening locally to protect immigrants. There is more Chicago can do. “In our conversations with the City, we [say we] want to get rid of the carve-outs. And they’ll say, ‘Well, we don’t actually enforce the carve-outs in any way. We don’t collaborate with ICE in any way, so you don’t need to worry about it,’” Anzures summarized. “But if there is a new administration that starts using a bully pulpit to get cities to cooperate with them, we need to codify these things.”

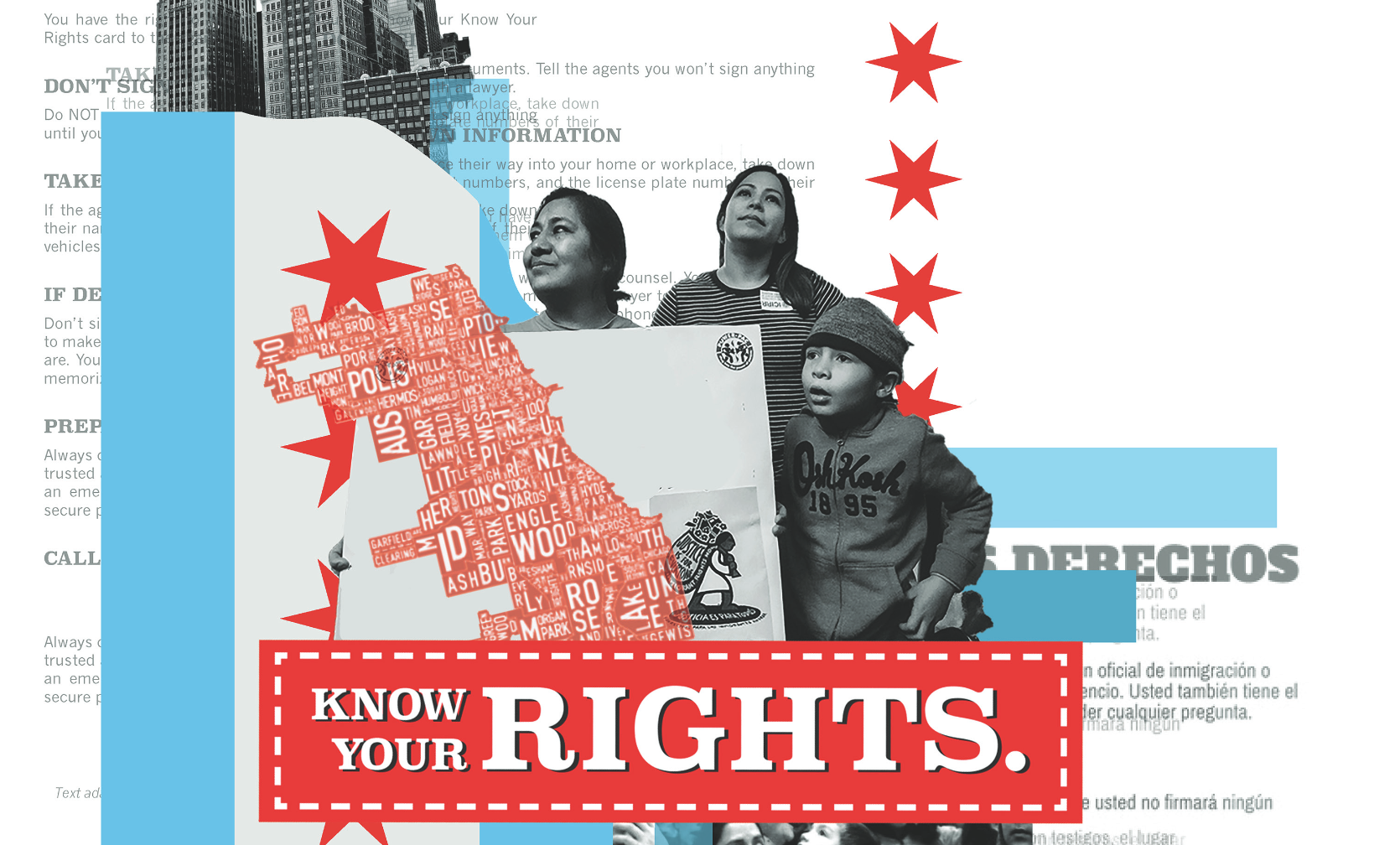

For printouts detailing your rights and information about what to do when confronted by ICE or police, click here for English and here for Spanish.

Glossary

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)

The policy started by the Obama administration in 2012 that allows certain undocumented immigrants who entered the United States as minors to receive a renewable two-year period of deferred action from deportation and eligibility for a work permit. As it is an executive order, DACA is under threat of being discontinued by the Trump administration.

DREAM Act

Federal legislative policy first introduced in 2001 by Representative Luis Gutiérrez and later debated in 2007 and 2010 that would have granted conditional or legal residency status to young undocumented immigrants who met certain requirements. Given that the federal DREAM Act has never passed, several states including Illinois have passed their own state DREAM Acts, generally aimed at granting in-state tuition rates to qualified undocumented students.

Chicago Municipal Immigration Policy Working Group

A group that includes Asian Americans Advancing Justice Chicago, the National Immigrant Justice Center, the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, Organized Communities Against Deportations, Southwest Organizing Project, the Korean American Resource and Cultural Center, Chicago Community and Worker’s Rights, the Chicago Religious Leadership Network, Comité de Trabajadores Unidos—Immigrant Workers Project, Mujeres Latinas en Acción, Latino Union of Chicago, Enlace Chicago, and others.

Welcoming City Ordinance

The city ordinance passed in 2012 that ensures undocumented residents of Chicago will not be detained by local police at the request of federal authorities. CPD will not communicate and/or cooperate with ICE under most circumstances.

The “carve-outs”

Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance currently has four carve-outs, or exceptions, that allow CPD to communicate and/or cooperate with ICE in cases where someone

• has an outstanding criminal warrant;

• has been convicted of a felony in any court of competent jurisdiction;

• is a defendant in a criminal case in any court of competent jurisdiction where a judgment has not been entered and a felony charge is pending; or

• has been identified as a known gang member either in a law enforcement agency’s database or by his own admission

Corner hiring site

Any place (a park, a gas station, a Home Depot) where workers gather and make themselves available to employers who come to negotiate a job and a pay rate.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.