I first met the artist, writer, bibliophile, and shapeshifter most commonly known as Krista Franklin in January of 2019. We were gathered in celebration, about twenty or so of us, at a tapas bar in the West Loop after the opening of a mutual friend’s exhibition. I’d arrived just shy of being late. As I was quickly reconnecting with and giving my love to the host, our party was seated, and as we continued to talk we took up residence at the far end of a long table. Franklin and another mutual poet friend joined us, making a raucous foursome of Black poets. Part of what made her so memorable that cold January evening was a quick wit and an irresistible laugh, but most of all was her voice, deep and rich like butter on a Sunday biscuit.

It’s July 2019. 1104 S. Wabash. Franklin and I are at Columbia College Chicago, in the studios of the Book and Paper Arts Programs. She’s only in this studio for a few days, and so tonight she’s planning on staying until the building closes at eleven. This week she will spend ten to twelve hours on the grueling process of making paper. “I’ve been doing it for about five years straight… It’s not backbreaking but it is laborious. And it’s heavy work—you’re picking up a lot of weight. Wood. And water too.“ Today she is working with abaca, a fiber from the Philippines. “I don’t really have a lot of access to it except for here. It’s really translucent, especially when bleached. It can be semi-translucent when dried. It’s one of my favorites. I use it as a laminate.”

As we sit on stools near the studio’s large loft windows, Franklin looks at me with the intuitive intensity of an artist in anticipation, her mind coiled tight before the lunge. Franklin, who is originally from Ohio, has been living in Chicago for eighteen years. She came here on a whim: “my best friend lived here.” The two women had made a pact that they were going to apply to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago for grad school. Franklin didn’t keep her end of the bargain, and when her friend applied and got accepted, Franklin stayed in Dayton, Ohio. A year later, her best friend was still working on her masters and needed a roommate. “I was thinking, sitting…, chilling, and I was like, ‘I am not doing it.’ And the next day I was like, ‘Okay, I’ll move.’ I sold off everything I couldn’t fit in my little car. Lived with her for a year and then struck out on my own.”

Once engaged to artist Stephen Flemister, she came to the South Side for love, but when that relationship ended, she stayed. Franklin adores her home in Bronzeville because it is “emotional[ly] and physically charged,” adding, “to say that I live in Bronzeville… that space where all this Black history erupted.” She notes that “I won’t always live there, I won’t always live in Chicago, but it has been one of the most critical spaces for me to live in for many many reasons, including and up to some of the more violent things that happen in the city.” For this lover of Black history and story, this fighter city—constantly identifying itself in opposition to something else—makes an apt home.

For the better part of the past decade Krista Franklin’s work has spanned genres and media like light spans a dark room. In 2012, Willow Books published Franklin’s chapbook Study of Love & Black Body. In its title poem, she quotes André 3000 thanking mothers and fathers in the epigraph, while later in the piece effortlessly flaying your heart with truth—in hard smacking lines like “To the child her mother said: Children are like tiny anchors.” and “Not one thing can stand the weight of a chain.”

In 2015, Franklin exhibited the project “Like Water” at the University of Chicago’s Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture. “Like Water” combined writing and visual art to create a shapeshifter, a fictional young Black woman named Naima Brown. The exhibition examined how Naima moves through the world as she figures out that she can shift and change herself into anything—from an animal to another person.

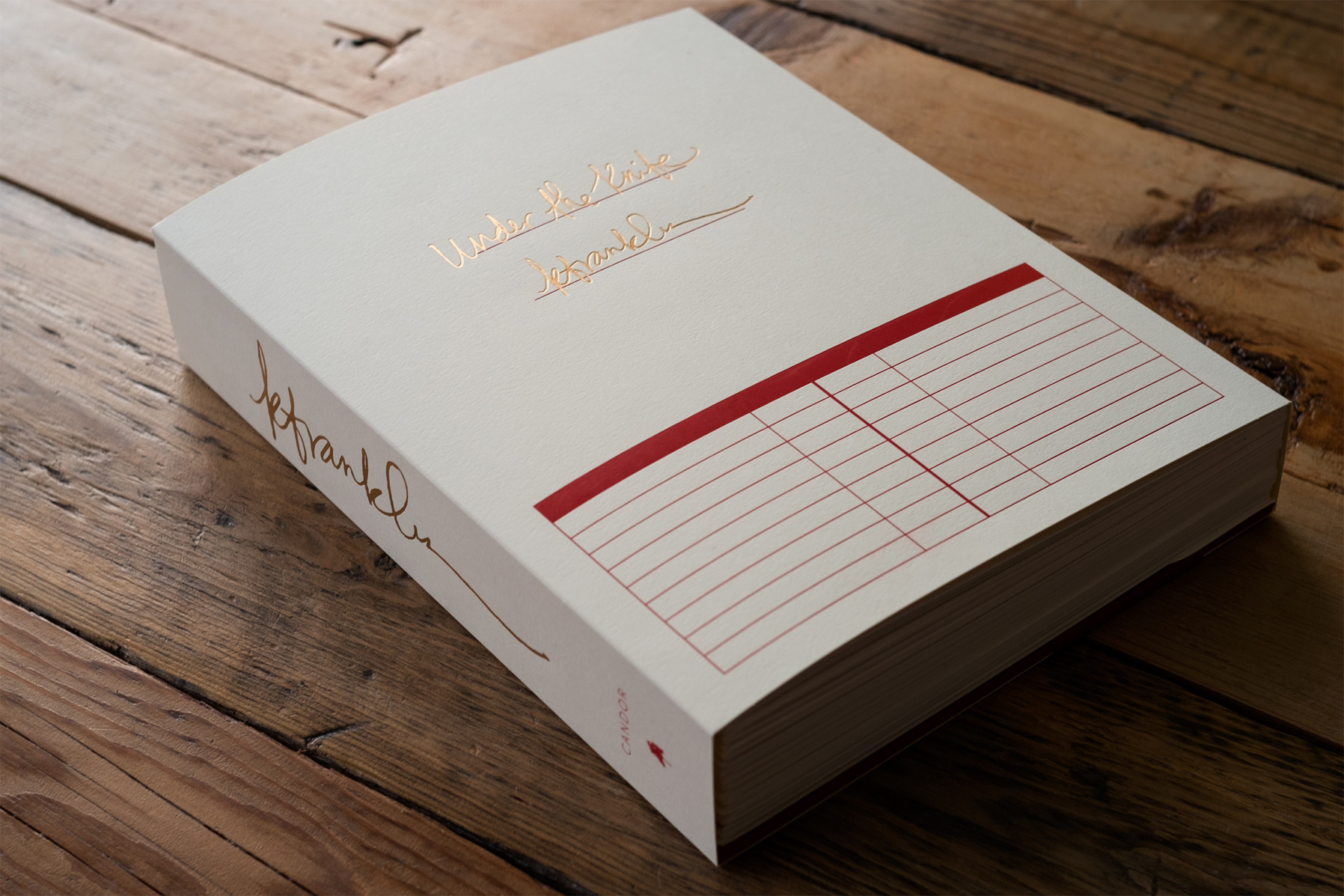

In 2018, Franklin released Under The Knife through the artist book publisher Candor Arts. The hand-bound book has a clinically stylized look; the cover resembles a medical file. “For me, the stitching was an aesthetic as well as a conceptual conceit around the stitching in my body,” says Franklin. “It is a non-traditional book in a lot of ways. It is designed to be many things: a memoir, a work of art, a family history, a photo album. It’s an art book, but it does tell a non-linear story about…my mother’s side of the family and some of the traumatic experiences around mothering and motherhood. Woven throughout that is my own story with reproductive issues as well, and…having had multiple surgeries to deal with that.”

Franklin’s new book, Too Much Midnight, was released by Haymarket Books in early April. It is a holy work in the canon of Black female liberation theology. A chronicling of Franklin’s conjuring. A culmination of horrors and histories told through the vulnerable lens of a life lived openly. In Too Much Midnight, Franklin draws from a gri gri bag of awakened realities—the larger canons of pop culture and art history, as well as the histories of the African diaspora and Afrosurrealism. The book features thirty pairs of poems and artworks, as well as an interview with the artist.

Franklin tells me that “the courage [to tell these stories] wasn’t hard, because I come from a family that’s very forthright. I won’t say most Black families, but I think [in] a lot of families in general there always seems to be this huge cloak of secrecy around shit. My family doesn’t have that. We definitely have stories that I don’t know. The women in my family have a right to their own privacy. But when it comes to their childhoods and the experiences they had to endure, they are really open. I remember when I was younger, my biggest question [for my mother] was ‘Is it ok that I am writing about this, that, or the other?’ Her question would be ‘Is it true? Then OK. Carry on.’” She laughs at the memory.

One of the things that touched Franklin’s life growing up was that her mother and aunts were raised in an orphanage in Xenia, Ohio. “They were taken to this orphanage [when] my mother was about six or seven. She’s the oldest of four. They were taken from the home because my grandmother could not afford to take care of them. It was a financial issue, poverty-related. Not abuse or anything like that.” Her mother grew up there until about the age of sixteen. She graduated from high school and then went home to help get her sisters out after that. “I would go back to that orphanage every summer. They have a reunion every year and my mother was just at that reunion this past weekend. So it was a part of our life story. It wasn’t this thing that anyone was ashamed of. Even my grandmother, she was kind of shameless, you know? May she rest in peace. Even if she did have shame around losing her children, she never showed that to me. Also, they still were in contact with her. So I was still very much a part of my grandmother’s life. It wasn’t this huge ordeal.”

Franklin’s creative process involves a lot of obscuring. “When I started writing Under The Knife,” she says, “I intended for it to be a straight memoir, just all the way through, starting at their [her mother and aunts] story and going straight through and then landing at my last surgery, which was a hysterectomy. My psychic grappling with this idea, this speculative notion that I had around my body going ape shit, because of the particular traumas I had in my imagination around what it means to mother a child. And the idea of loss. I recognize Under The Knife as being in a literary legacy of capturing the narratives of Black women. And I kinda wanted…this kind of echoing throughout the book, [but] I could only really achieve that by deconstructing the book. I wrote up to a certain point. I couldn’t really get much further, once I got better from my surgery…so then I took it to the cutting floor and chopped it up. Did a whole bunch of interventions in the writing—including painting over pages and obscuring certain passages. Digitally manipulating certain things and introducing family photographs, introducing medical records, just a number of different kinds of archival materials to capture the story that really can’t be told—or really fully understood.”

Critics have drawn connections between Franklin’s work and that of jazz musician Sun Ra. (“People talk about Sun Ra and my work all the time, and to that end, I’m very flattered because he was a master.”) But, she tells me, she didn’t come to these concepts that she explores in her work through him—instead, she discovered ideas of Afrofuturism through reading science fiction novels. “Octavia Butler is much more of an influence on me than Sun Ra is. The Neptunes are more of an influence. I mean, OutKast is more of an influence on me than Sun Ra.” Franklin was born in the 1970s, so she “didn’t even find out about Sun Ra until much much later in my life… I appreciate the legacy of Sun Ra, I was drawn to him because of his ability to myth-make a whole legend around himself creating his identity… I am compelled by his persona.” But her inspirations were sci-fi writers like Nalo Hopkinson, Tricia Rose’s book Black Noise, and Public Enemy—she’s a fan of what she calls their “sonic displays.”

When I asked Franklin about what it means to be an Afrofuturist, about the common marriage of her name and the term, she quickly turned the question on its head. “What are you talking about when you say that I am an Afrofuturist artist? I know what I am talking about, because I am making the work. I used Afrofuturism in graduate school [at Columbia College] and Afrosurrealism as a way of thinking about certain things in my work. The idea of the speculative, the idea of horror, the idea of the grotesque, the idea of the dream space, the dream state….How have Black people, African people, people of color, [Latinx] people—how have we used these systems that are very complicated—space, astronomy, metaphysics, astrology, Tarot divination systems…used shells to tell people’s futures. These are the things that rattle my cage, that I am excited to talk about and wish to talk about more than using these very reductive statements that—oh, her work is Afrofuturist. Why are you calling it that? Is it the outer space references that I am making? Is it the fact [that I am] referencing gods and spirits? What is it about this work that makes it Afrofuturist or Afrosurrealist?”

Krista Franklin is real AF. When I tell her of my own emotional response to her work, of my own seven-hour myomectomy, of waking up alone and undermedicated—she holds me with an overstanding gaze. After an afternoon of connecting through laughter, while sighing and bonding over the stories of our Black female bodies in the Western medical system, I leave Franklin to her work of constructing, examining, and intervening. She is sloshing through ephemera—piles of clippings and album covers, collected oddities of Blackness. The abaca sits ready for the next step in her process. An assortment of cut-outs and collage elements await her—scattered across a steel table—poised to be assembled and addressed.

AV Benford is a Food & Land editor at the Weekly. She last wrote about how marijuana legalization is off to a rocky start.