In the 1980s, the Near North Side’s Cabrini-Green Homes, a public housing project that was once synonymous with “urban blight,” became home to Free Street Theater, a company with a mission to challenge the persistent and violent segregation that divides the city. The ensemble moved into an abandoned funeral home adjacent to the Homes and worked with residents to help them tell their own stories. The critically acclaimed musical that resulted, Project! became one of Free Street’s defining moments; the show toured the country, and even made its way overseas to perform to sold-out London audiences.

Free Street has been at the forefront of radical theater in Chicago for over five decades. It was founded in 1969 with the mission of making art accessible—both financially and physically—by offering free or pay-what-you-can admission and bringing performances to Chicagoans in their own, often underserved neighborhoods.

You could then—and still can—find Free Street shows in public parks, plazas, and other nontraditional spaces. These diverse locales often mirror the multiracial, multigenerational make-up of the company itself. Prioritizing inclusion from its inception and making affordable live theater available outside of downtown has been a strategic way to challenge the racial and economic inequities that define and divide the city.

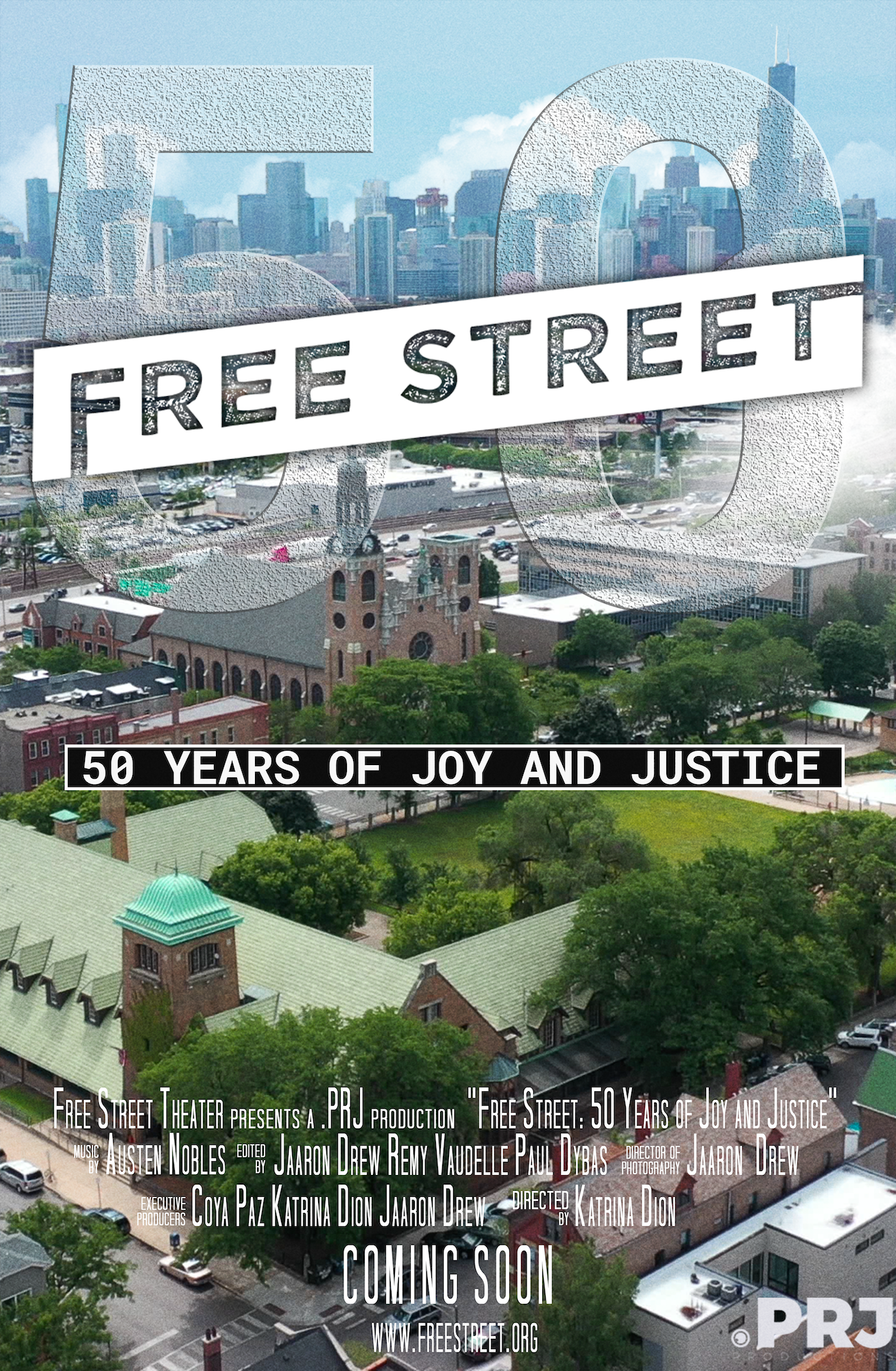

On February 17, Free Street hosted its annual anti-Valentine’s day fundraiser, “Radical Love,” at Columbia College Chicago’s Film Row Cinema in the South Loop. The event doubled as the world premiere of the documentary Free Street Theater: Fifty Years of Joy & Justice. Originally conceived as a way to connect the theater’s alumni across the years, the documentation of live performances resulted in a snapshot of the living, breathing ecosystem of artists that define Free Street in its fiftieth year. The documentarians stitched together raw moments with intimate interviews to capture a comprehensive history of each era of the company’s growth.

The centerpiece of the film is “50 in 50! A City Wide Celebration,” a daylong event held in the summer of 2019 that featured free fifteen- to twenty-minute performances in each of Chicago’s fifty wards. This massive and symbolic undertaking was the company’s way of making sure that no corner of the city is forgotten—but Free Street is invested in doing more than simply showing up.

Free Street’s work is predicated on the idea that live theater has transformative and healing potential, and that engaging audiences through the arts can also open the door to education on matters like harm reduction, community care, disability justice, and prison abolition to name a few.

In an op-ed published in the Reader, Free Street artistic director Coya Paz recently wrote, “Isn’t this the promise of the arts—that we can create new worlds, new relationships, new ways of understanding each other?” This kind of alchemy is theater’s most powerful tool. “There are not a lot of opportunities to come together in joyfully and complicated ways,” Paz said in an interview with the Weekly. “In the digital era, this opportunity to come together live is crucial.”

More broadly, the Reader op-ed addressed the lack of diversity at the then-imminent Academy Awards, and how that kind of industry gatekeeping can be found in Chicago’s theater scene as well. Awards and reviews from local institutions and media serve as a “cultural archive,” she argued, and when institutions and media concentrate their attention on productions in white, affluent sectors of the city, those outside that narrow scope are erased. This pattern, said Paz, creates a “closed circuit” that keeps resources like funding from reaching those that need it the most.

In the op-ed, Paz provided a thorough economic breakdown of Chicago’s arts scene, but ultimately brought her points back around to the larger national conversation. When institutions fail to include diverse stories, she wrote, it distorts the idea of “who and what is American.” At a time where the Federal government is redefining laws and policies to restrict who can be a part of this country, art is meant to serve as a conduit for expansion in the face of exclusion.

Whether local, national, or international, storytelling is important, and documenting and amplifying stories through media and other mechanisms immortalizes them. When the archives contain the same story regurgitated four times (see: A Star Is Born), it sends the message that certain narratives are all that is possible. When it comes to leveraging financial resources, original stories become a risky investment.

Do artists have to compromise their stories, bringing them into a conservative, commercial nexus—whether Hollywood or Loop theater—in order to be seen? Or do they keep doing the imaginative work they’re doing in the corners where they’ve been doing it for years, and demand to bring the conversation to their own turf?

Free Street did just that in 2018 by opening its Storyfront Theater in Back of the Yards. Housed in a storefront rented from a local family, the Storyfront serves as a local nexus for South Side communities to come together to experience experimental performances, take an acting class, or attend a “know your rights” workshop. In 2019, the Storyfront hosted a series of participatory workshops led by artist-in-residence Quenna Lené as developmental work for a piece called “Re-Writing the Declaration,” which invited participants to collectively reimagine the Declaration of Independence as a modern tool for social justice.

Fifty years is a long time for a theater company to not only have survived, but to continue thriving in accordance with its original mission. By creating and maintaining spaces where people can come together to reconsider the language, motives, and intent of a document that once brought freedom from tyranny, Free Street continues its campaign to be an agent of social change.

Jeremy is a Bolivian-American artist, writer, and performer. They are currently working on House of Worship, a television series that dramatizes the rise of house music in the queer Chicago underground. They are actively looking for collaborators with lived experiences that can help build this story. They last wrote for the Weekly in February about a day and night celebrating the legacy of Frankie Knuckles.