Brian McCammack wants to push against the idea that the history of African Americans’ use of public space in and around Chicago can be summed up simply.

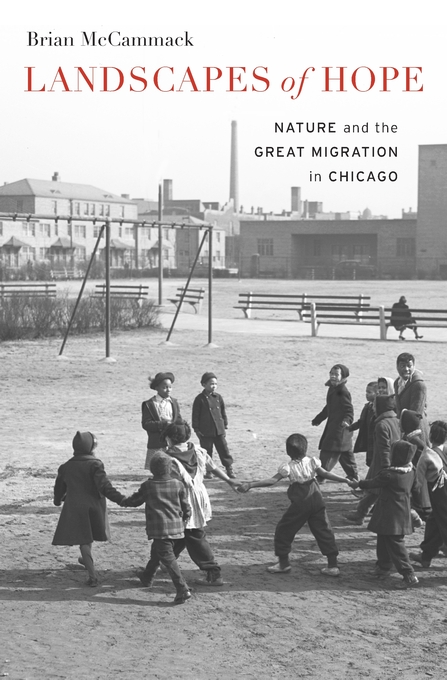

At the Seminary Co-op bookstore in Hyde Park last month, McCammack, author of the recently published history Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago, spoke to University of Chicago history professor Adam Green about the complex ways that African Americans coming to Chicago in the Great Migration interacted with nature.

McCammack’s study originated as his dissertation at Harvard, and has continued to pull at him as an assistant professor of environmental studies at Lake Forest College. He wanted to counter sharp binaries that have been constructed by scholars in both environmental studies and African American studies. The writer Richard Wright painted a picture of a greenless South Side in writings such as Native Son, while the Chicago School of Sociology draws a boundary between the urban environment and the natural. By contrast, McCammack wants to show how green space in and around the city was crucial to African American communities during and just after the Great Migration, from 1915 to the late 1940s.

McCammack writes that nature was not only “a political proxy for racial inequalities” but “a good in and of itself, freighted with multifaceted cultural significance that reveals black Chicagoans’ modern urban lives to be more varied—and more complex—than is typically understood.”

The term “landscapes of hope” is meant to highlight new attitudes towards nature for African Americans coming from the south, where nature was often defined by labor such as slavery and sharecropping, to an urban space where the natural came to be associated with leisure. One of the drawbacks of the book is actually the sheer number of times McCammack feels the need to use the full phrase “landscapes of hope,” which takes away from its impact.

The book’s parts are roughly separated by their theme, but also somewhat by timing, which can be disorienting as parts dive back and forth through timelines. McCammack begins with Washington Park, public spaces, and other local spaces before shifting into how black communities interacted with green space outside of the city itself. His goal is less to draw the timeline as a linear path, and more to complicate previous assumptions about the way that post-Great Migration Black Chicagoans interacted with their green and public space.

“One of the things I really try to get away from in the book,” said McCammack at the Co-op, “is what I feel to be a potential pitfall of a lot of environmental justice scholarship: it tends to at times victimize the African American community and rob that community of agency in a way that we don’t see that place-making happen.” This work to reestablish the narrative of Black communities’ agency and history of protest over their green space has earned his book the 2018 Frederick Jackson Turner Prize, an award given each year by the Organization of American Historians for an author’s first book on American history.

Holding on to accessible public space was not easy for Black communities of the 1910s, 1920s, and beyond. White violence in urban public spaces was common as the communities shared the use of spaces such as Washington Park and 31st Street Beach. In 1919, white gangs haunted African Americans for days of violence following an incident where a rock thrown by a white man drowned seventeen-year-old Black teen Eugene Williams, who had accidentally drifted over an invisible line of segregation between two beaches. Meanwhile, many of the spaces specifically for Black communities were poorly funded and maintained and were clearly inferior to those meant for white communities.

Ultimately, Black communities were able to establish their own institutions and get resources they’d been looking for, mainly through New Deal funding in the 1930s. But it was a trade-off. These institutions and resources came only after white communities ceded shared public spaces, and at the cost of increased segregation. When Washington Park opened the city’s largest public swimming pool, the community was thrilled—but some found it difficult to look past the fact that the suggestion had originally come from white communities as a way to keep Black communities from invading ‘their’ beaches of 57th Street or Jackson Park.

“Racial antagonism had simply changed addresses,” writes McCammack about this stage of the fight for access to public space. As the Black Belt expanded, white communities ceded space, and segregation increased. Black communities gained access to beaches as violence in Washington Park faded, but it was only because they were no longer shared. Improvements for 31st Street Beach were finally made—but by then, the Black Belt was fighting for use of the even nicer Jackson Park Beach, which was closer to where the Black cultural elites lived at the time.

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

Many Black Chicagoans attempted to avoid this fraught urban landscape all together. The final three chapters of the book center mainly on the areas outside of Chicago, where city residents encountered nature. McCammack said at the Co-op that while it may seem to some as though the majority of the book doesn’t have a connection to Chicago, Black Chicagoans “were in this ex-urban space, in southwestern Michigan, in downstate Illinois, experiencing environments beyond just the urban landscaped green spaces of places like Washington Park.”

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a national New Deal work relief program, attracted young men from Chicago by appealing to their love of nature and sports. But the CCC was not much of an escape from urban environments: while the men could send money home to the South Side, they had to do back-breaking, mind-numbing manual labor such as digging in often segregated, isolated camps.

The largest CCC camp in the nation was the one that built the Skokie lagoons, which were meant for flood control as well as to attract leisure seekers out to the North Shore. The labor was African American, McCammack said, “to an extent that I don’t think people realize,” and yet the communities that benefited were white, and the overseers that supervised them were white. Adam Green said it was reminiscent of the chain gang, and McCammack agreed, saying that this relationship to nature was more akin to a tradition of Black labor, of sharecropping and slavery—the traditions that these people or their parents had left the south in order to escape.

But Black communities did escape to the natural landscapes outside Chicago in a way that provided for leisure as well. Idlewild , Michigan was once such place, an enclave and resort for Black elites where they could escape to a natural landscape. Even this was not an escape, however, as it was surrounded by sometimes hostile white communities. These elites made sure to pass on that access to nature, particularly to children in working-class communities, by working through organizations like the YMCA and the Boy Scouts to create camping opportunities that would expose children born in the city to the wild nature outside of it. As Black children spent time at places like Camp Wabash, other working-class Black communities fought for their right to continued open access to the forest preserves that surrounded the city.

Intraracial politics were not simple at the time, and McCammack leans on Chicago Defender archives to reveal how Black communities struggled with respectability politics. When Washington Park was still used by white communities, Black cultural elites often criticized working-class use of public space that they worried would “confirm racist notions,” including baptisms in the Washington Park lagoon, fighting at interracial baseball games, and the playing of the banjo on tennis courts.

This came to a head in the 1930s, when the Great Depression hit and Washington Park became a center for political pushback. The Communist Party used the park as a radical organizing space, which made elites wary. The first Bud Billiken parade was a celebration of Washington Park, a use of green space that brought the community together and was meant to uplift Black youth—but McCammack writes that it had a tinge of the desire to pull the use park away from more subversive working-class protests.

During these protests led by the Communist Party, groups would gather, and if they heard an eviction was taking place nearby, they would go as a crowd to stop it from happening. In 1931, policemen killed three Black men at one such protest—in an event named the Chicago Massacre—which led to tens of thousands of African Americans protesting in Washington Park. A brief moratorium on evictions followed. It was, McCammack said, “the moment where you see that the working-class African Americans are able to utilize that green space of Washington Park and accomplish something politically.”

The question of agency is a crucial one for McCammack’s book, which ends with a rushed epilogue referencing the years after his study ended. The question of how Black communities have fought for their public green space over the years leads to the controversy over the future Obama Presidential Center (OPC). Many audience members brought up the issue, as did Adam Green. While McCammack’s epilogue ends with a positive note about the OPC, he was significantly more ambivalent at the event.

McCammack pointed out that if the Center had chosen to build on Washington Park, it would have been almost on the spot where communists and protesters once came together.

“There is an African American heritage there dating back decades upon decades,” said McCammack. “It’s tougher to make that case with Jackson Park only because that’s where white Chicagoans set that racial boundary in the 1930s.” But there was a counterpoint to that as well: McCammack thought there was a potential for great symbolic value in having our first Black president’s Center as “a mark of inclusion in spaces that African Americans literally had to fight for, that African Americans had been excluded from.”

Other aspects of the OPC made McCammack nervous, particularly the idea of “a private enterprise in a public space,” and the potential for inaccessibility. He also pointed out how certain spaces have been funded, noting that the park district has left tennis courts in disrepair at Washington Park as Jackson Park gets more investment. He wondered aloud if the OPC could have changed the amount of investment put into Washington Park. But as Adam Green pointed out, McCammack’s book suggests that African Americans have never been passive about the use of green spaces—so “at the very least there needs to be consultation of what community preferences are,” he said, referring to the Community Benefits Agreement that South Side activists are urging the Obama Foundation to sign.

McCammack agreed, drawing on the example of how Bronzeville’s Madden Park first came to be. While community leaders and Black cultural leaders like Ida B. Wells spearheaded the campaign for the park, in the end “the Defender puts it to the community as a whole, saying, ‘Where do you want a park? What kind of park should we have?’ And you eventually have people from all over the South Side signing onto this,” said McCammack. While many are worried that the Obama Center seems to be a very top-down process of decision-making, Madden Park was “much more of a grassroots movement.” He suggested that it would be a better model for the Obama Foundation.

McCammack’s comments at the event show how his research can be immensely valuable for debates on movements like the community organization around the Obama Center. Landscapes of Hope’s reflections on our historical use of public and green space, and on the way we choose to invest in those spaces, particularly in Black communities, is as relevant as ever.

Leah Rachel von Essen is a staff writer at the Weekly. She is a Hyde Park resident who writes for Book Riot and reviews books at While Reading and Walking. This is her first piece for the Weekly.