Tea is a social glue or excuse for us to sit down, know a little bit of each other, and find the right words to share,” said Shaolong Jiang, the owner of an authentic Chinese tea house in Little Italy, as he deftly prepared small cups of tea at the counter. “That was the idea of a tea house in the United States.”

Whether you’re sipping oolong while catching up on assignments or savoring a scoop of tea-infused gelato, Living Water Tea House is a relaxed environment enlivened by a sympathetic owner keen for good conversations. The tea house is lit up brightly and features a lush bonsai centerpiece, with small tea cups and instruments tastefully arranged across a set of shelves. The negative space of the white walls brings out the soft happy chatterings of tea enjoyers.

Jiang was a Chinese pastor at New Life Church in Bridgeport when he had the idea to create a community through sharing tea and deep talks. He first had the concept for Living Water when he visited a tea house in China that incorporated the Daoist principle of wu wei (無爲), or “doing nothing”. This seemingly contradictory philosophy encourages followers to be at peace while engaging in intense actions. An American equivalent may be something like being “in the zone.”

At the Chinese tea house, Jiang became drawn to the lively community of youth sharing personal stories. He started simulating that setting while in seminary in Chicago in 2018. Jiang began in a local church space with a group of twenty regular church attendees, before moving into a brick and mortar location in Little Italy in 2020. The name of the tea house, Living Water, is a reference to a passage from the Bible in which Jesus Christ says, “whoever believes in me, as Scripture has said, rivers of living water will flow from within them”.

“I always have this quest for identity as a Christian or as a Chinese, and I always felt like I need something to make myself feel settled,” Jiang said.

Jiang has realized that quest through the tea house by creating a culturally inclusive space for Chinese international students.

Since its opening, the Living Water Tea House became a wellspring of imported Chinese teas and a welcoming space for Chinese student artists. The tea house first started selling milk tea to attract customers. Once Jiang secured a footing in the neighborhood, he incorporated traditional, authentic tea culture. Today, Living Water offers puer, oolong, jasmine, and green tea, as well as tea cakes and gelatos with corresponding flavors. Jiang said there are even some ideas underway for tea beers to appeal to local tastes.

“We find our way to be local and blend in with Chicago culture,” Jiang said. “We became a Chicago rather than a Chinese thing.”

While serving tea, Jiang likes to praise the tea from his hometown Qingdao—Laoshan green tea. Grown in the coastal region, the wind from the sea imparts the tea with a sweet melon aftertaste, Jiang says. Besides his gusto for the variety of tea, Jiang emphasized the importance of developing relationships with people in the supply chain in order to get the best teas.

“Tea is like wine, whiskey and cheese in that you must deal with a person [for your] personalized, small business to have a character,” Jiang said.

In the U.S., tea consumption is dominated by black tea—around 86 percent—followed by green tea at 13.6 percent, with less than a percent of other teas, according to the Tea Association of the United States Inc. Still, over the years, Jiang has observed more American clientele who are just as equally interested in tea houses.

“A lot of Americans want cultural exposure or seek something outside their commercialized coffee, right? So that’s where we show up” he said.

Every other Friday night, Jiang also leads a small tea group in the Zhou B Art Center in Bridgeport.

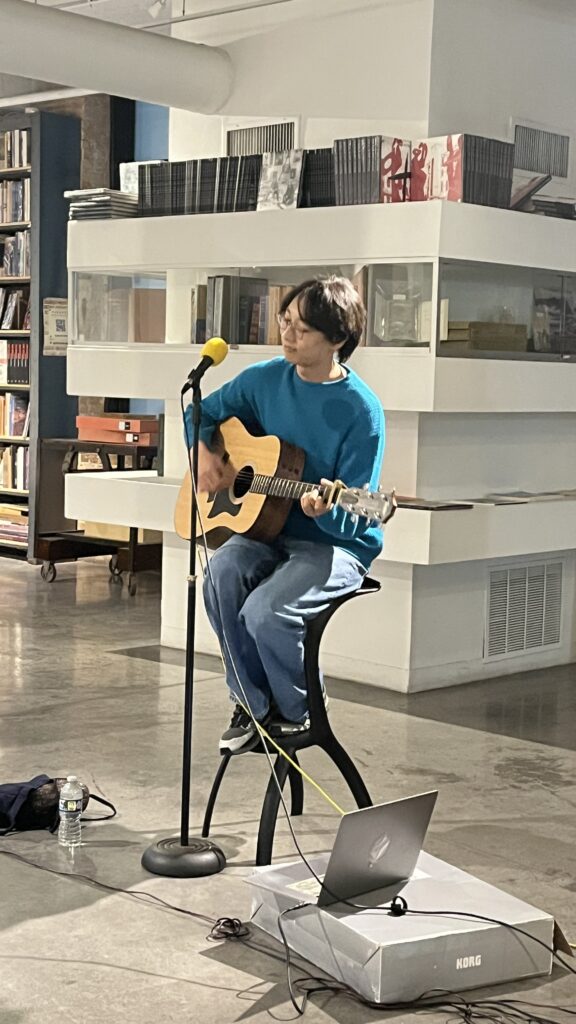

Haotian Wang, a master’s student of sound arts at Northwestern University, has performed some of his compositions through collaboration with Living Water. At the Zhou B Art Center, he plays acoustic guitar and hulusi, a Chinese instrument made of a gourd and flute.

Wang said he first heard about Living Water through an online post that commented on the owner’s flair for storytelling and profound anecdotes. This piqued his interest to visit, and eventually to become a part of the music scene at the tea house.

Wang said what he enjoys most about Living Water is the opportunity “to connect with people from different backgrounds, and see how my music communicates about my culture, my identity, and to share them with people here in Chicago.”

At one such performance on November 15 at the Zhou B Art Center, while listening to Wang’s meandering and melodious music, tea enthusiasts gathered as Jiang swiftly boiled and cleaned the tea, then poured it into small cups while talking about its heritage and the tea culture. He handed off cups of tea to an occasional passerby at the gallery and asked for their feedback.

Chelsea Zhao (she/her) is a contributing writer at South Side Weekly.