Andrea Miroslava Ramirez’s room is adorned with sketches, prints by other artists, a toddler bed for her great dane, Zuko, and a makeshift workstation with shelves and tools galore.

Ramirez is a Mexican-American artist, visionary, art teacher, part-time volleyball referee, and my friend. For a while, she was just my college roommate’s little sister who was studying science at Loyola. But after many smoke sessions, Ramirez became one of my friends too.

“In an environmental science class, I started making scobies…it’s basically vegan leather that you grow out of cultures. And I was really excited about that and the design aspect, and making art with it,” Ramirez said. “I was bringing it up to my professors and they wanted me to focus more on the science part.”

Instead of following that advice, she realized her interests lay elsewhere. It was a pivotal moment that eventually led Ramirez to switch her major to art. However, her relationship with art and creating began from a young age through her grandmother and great-grandmother.

Ramirez comes from a line of matriarchs. She fondly remembers sitting at the kitchen table and sewing napkins with her great-grandmother. Her grandmother followed suit by also handing her crafts to keep her occupied.

“She gave me a bunch of Tupperware and scissors and glue and sponges. And I would just go to town,” Ramirez said. She recalls having intimate moments like these since the age of two.

Now twenty-four, her art has been continuously cultivated by her family. Ramirez’s mom owned a papeleria, or stationary store, in Mexico, and her dad’s resourceful inventions would later inspire her to make due with unconventional tools like borrowing plastic putty knives from family and friends who work construction.

Through the years, Ramirez has grown into her artistry while remaining intentional. She describes her work as “socially engaged and unapologetic.”

Ramirez’s work delves into cholo culture, and more broadly her experiences as a Mexican-American daughter of immigrants. Mexican Americans have for years created subcultures of their own while holding close cultural references.

A commonality that continues to thread her work is the theme of deviance. Street culture can be looked at as deviant by first-generation immigrants, but some Mexican Americans have adapted a distinct urban style going as far back to the 1940s Zoot suits era, which was characterized by oversized suits with exaggerated proportions. The suits were a form of cultural resistance that also created a sense of identity. That duality also holds true to the core of the cholo lifestyle.

“I’m coming at it through that lens of: I want to see the history of where this garment comes from,” Ramirez said. “I want to see why people are thinking this way about it.”

Through research and her own experiences, Ramirez began to create by referencing the myriad Mexican-American experience. As an undergraduate, Ramirez’s piece “Mi Baile es Mi Llanto de Guerra,” or “My Dance is My War Cry,” was showcased at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, It features a hand-embroidered flannel typical of the cholo wardrobe.

The flannel opens to reveal two messages: “sé que solo así luchando triunfaré” and “con mi color hasta morir” which translate to “I know that only by fighting like this will I triumph” and “with my color till death,” respectively.

To accompany the clothes, Ramirez made a video of herself dancing cumbia, a genre with deep roots in Mexico City, the home of her parents.

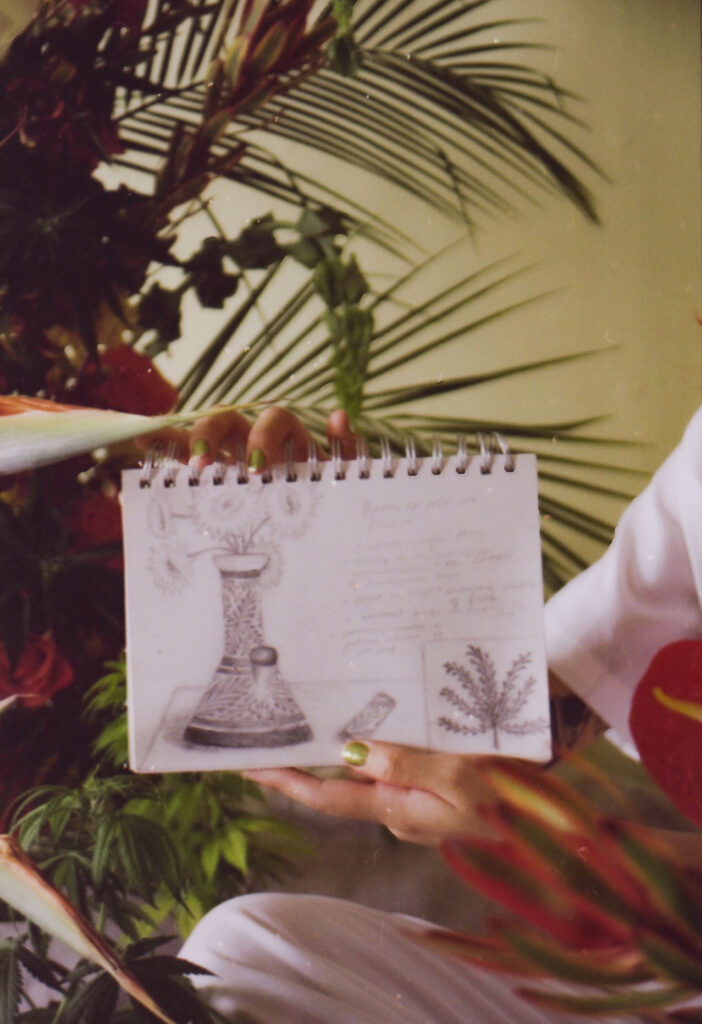

“It’s literally just trying to navigate living in between cultures,” Ramirez said. Part of her extensive portfolio is a Mexican ceramic pottery, or talavera, set of a bong, ashtray, and rolling tray titled, “Hierba Mala Nunca Muere,” which translates to “Weeds Never Die”—a common saying with double meaning.

Through tears and a broken voice, Ramirez recounted the vision behind “Hierba Mala Nunca Muere.” “What if I make something really beautiful,” she thought about cannabis critics, “and they can’t look away from it?”

For generations, cannabis consumption in the Latinx community was heavily stigmatized, and it’s still largely frowned upon today. Ramirez remembers her uncle being ostracized for his open use of the plant when she was younger.

“Making that was for my grandmother, for my grandfather, and for them to, again, self-reflect on all the fights they have with him, all the bullshit they put him through.”

The smell of weed and incense burning to mask it transports Ramirez to the times her grandmother tried to hide the obvious. Making the set in traditional Mexican talavera ceramic style was purposeful. The working title was, “Mamá, solo es un florero” or “Mom, it’s just a floral vase.”

“It’s just a really fucked up convoluted mess of emotions that I feel looking at that because it’s like, everybody says it’s beautiful, but let’s talk about what it is,” Ramirez said.

Ramirez meticulously pours her soul into her craft, and everything she makes says—if not screams—a larger message. Her artwork is conversation-provoking and treads through complicated themes of generational trauma and, in some instances, bridges the gap between generations.

“[Cannabis] is something that shouldn’t be demonized,” she said. “This is something that, again, is literally growing out of the earth.”

The creation of “Hierba Mala Nunca Muere” led other relatives to reach out and commission bongs for themselves. Her artwork was displayed in Loyola, which gave her artwork validity to her parents. “I think the fact that it was holding space in Loyola, in this institution, I think meant a lot more,” she said.

Ramirez plans to continue her path in higher education and is headed to the University of Illinois on a full ride for an MFA program in the fall.

“I think for me, pursuing higher art in higher education just means that my work is going to be conceptually stronger,” she said.

Education has always been at the core of Ramirez’s upbringing. Her grandfather was a long-time director of El Valor in Pilsen that serves the community as early education and daycare. Now, Ramirez has followed in his footsteps as an art teacher at Queen of Universe elementary school.

Ramirez creates art that speaks to women like me with all its uncensored complexities. And I have watched Ramirez make sacrifices and be ingenious as a teacher with little to no budget. Her students are largely Latinx and her lessons revolve around giving their culture back to them.

“I just want them to make what’s important to them,” she said.

Ramirez’s “Mi Baile es Mi Llanto de Guerra” will be coming to the Chicago History Museum next year.

Jocelyn Martinez-Rosales is a Mexican American journalist from Belmont Cragin and the Weekly’s music editor.