Alongside federal funding, the result of the Census count that most directly impacts where we live is redistricting: the redrawing of electoral district maps for local, state, and federal offices that is often derisively (and correctly) referred to as “gerrymandering.” Much of the current attention to redistricting in Illinois has focused on the fact that, due to population loss over the last decade, we are likely going to lose a downstate congressional seat. But if recent history tells us anything, the redistricting process for state and city districts and wards will be a yearslong fight with no clear winners besides the political establishment.

In every decade since the 1980s—the first redistricting to occur after the passage of the 1971 state constitution—lengthy court battles have ensued over just about every aspect of the state redistricting process: the makeup of the commission tasked with creating state legislative districts, the facts taken into consideration by that commission, how ties are broken, and the racial makeup of the districts. Similarly, on the city side, the same fight over racial and ethnic representation on City Council, and racial and ethnic voting power throughout the city, has been fought from every angle. Latinx groups and officials claim maps on the South and West Sides are drawn to favor Black elected officials, Polish groups claim Northwest and Southwest Side maps are drawn to favor Latinx officials, and Black groups and officials regularly make claims of diluted political power. In a study of the 2010–2011 Chicago ward redistricting process, Northwestern University sociology and Latinx studies professor Michael Rodríguez-Muñiz described this as “casting Black and Latino political interests as a zero-sum game, [with] this juxtaposition help[ing] longstanding white overrepresentation escape public scrutiny.”

Part of this, many voting rights advocates claim, stems from the fact that the process of drawing both the state and city maps is an inherently political one, directly controlled by elected officials with a stake in the results, or their appointees. And while there are efforts to change this—bipartisan officials and advocacy groups have been pushing for a statewide “Fair Maps” amendment to the constitution for years, and last year Mayor Lori Lightfoot said she would push for an “independent citizens’ commission” to redraw the city maps—there always seems to be little legitimate political will from the city’s and state’s political leaders to do anything about it. Barring major changes in the political landscape, it seems unlikely that this round of redistricting will look any different than the previous four.

Since at least 1982, when Reader writer Steve Bogira examined state Representative Michael Madigan’s gerrymandering of state legislative districts, redistricting has been a means to consolidate political power and shut out rivals—political, ethnic, or otherwise. Bogira described how Madigan established a district boundary that ran south from Cermak Road to the city limits, politically walling off predominantly Black neighborhoods to the east from the then predominantly white Southwest Side. Although the segregated district map was challenged in a lawsuit from Black state legislators, including future U.S. Senator Carol Moseley Braun, the courts let it stand.

Nearly four decades later, Madigan—who became Speaker of the House (and chief legislative cartographer) in 1983 and chair of the Democratic Party of Illinois in 1988—is more powerful than ever. Governor J.B. Pritzker could present a problem for Madigan’s redistricting plans, however: the governor has voiced support for the Fair Maps Amendment. The COVID-19 pandemic prevented the legislature from voting to get the amendment on the ballot in November before a May deadline had passed, but Pritzker has pledged to veto any “unfair” redistricting map that comes across his desk, without defining what he would consider “unfair.”

Gerrymandering isn’t limited to state house districts. In the beclouted hands of Chicago’s mayors and city council members, seemingly picayune ward boundaries are battlegrounds upon which political favors are dispensed to the loyal and retribution is meted out to the faithless. And the process of redrawing them is as opaque to the average citizen as it is contentious among the power brokers.

To an uninitiated observer, the way a ward map can balloon, contort, and occasionally even shrink in size from one redistricting session to the next can appear almost arbitrary. It is anything but. In 2014, WBEZ’s Chris Hagan tracked the shifting boundaries of the 2nd Ward as it migrated northward over nearly a century. The ward underwent its first apparent bout of gerrymandering after the 1990 Census: it changed from a relatively regular shape to one that traced a ninety-degree angle that ran north from the 31st Street Beach on its southeast corner and skirted the Loop before turning sharply west to surround the University of Illinois at Chicago campus on three sides.

In 2002, the 2nd Ward got beefier, expanding to encompass more of the South Loop, growing a hefty nodule from the base of its western end and shooting a thin tendril from its southeastern boundaries down to 37th Street. According to Hagan, this was the result of a compromise between then-Mayor Richard M. Daley and Black and Latinx aldermen, but it also resulted in the 2nd Ward becoming the city’s most gerrymandered.

The ward shrank considerably in the 2012 redistricting, becoming leaner and moving far north, a shift Hagan (correctly) attributed to retribution by then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel for then–2nd Ward alderman Bob Fioretti’s lack of support. Fioretti lost his City Council seat as a result, and later ran unsuccessfully for mayor (and state senator, and Cook County Board president, and Cook County State’s Attorney). The ward’s current boundaries never venture south of Superior Street, and extend all the way to Wrightwood and Southport in Lincoln Park—some eight miles north of 31st Street Beach. The most significant contiguous land in the ward is the planned Lincoln Yards site; notably, most of the surrounding aldermen oppose the project.

Gerrymandering a ward is not as straightforward as it may seem: unlike other clout-heavy political maneuvers, ward map redistricting has to go through multiple rounds of approval before it’s adopted. (And in some instances, as with the 1992 redrawing, litigation can hold up adoption for years.) Elliott Ramos, WBEZ’s data editor, attempted to make sense of the process in 2012. He reported that potential ward maps have to be submitted to the City Clerk as an ordinance, something any citizen or community organization can do. But citizen-proposed ward maps rarely if ever get considered in the final redrawing of the city’s political boundaries. Because a new ward map is a piece of legislation, they need to be sponsored by aldermen. And—again, because they’re legislation—ward maps are actually written descriptions of what the boundaries will look like, rather than actual maps. Adding to the confusion, Ramos found multiple errors in ward map descriptions in the aldermen-sponsored ordinances. All of that adds up to create a system that, Ramos writes, “keeps the rest of us out of the loop and largely uninformed about the process.”

The independent citizens’ commission for redrawing ward maps that Lightfoot proposed last year could avoid the self-dealing, clout-heavy political retribution and overall lack of transparency that have plagued the process in previous decades. She faced immediate opposition from 28th Ward alderman Jason Ervin, who chairs the City Council’s Black Caucus, who stressed to WTTW that his primary goal is maintaining the number of wards with Black aldermen: “I know it’s not pretty, but we still have to create a map that could pass legal muster that represents the communities in the best fashion that can be done. The council has done a great job of drawing the maps that have been fair on the representation side.”

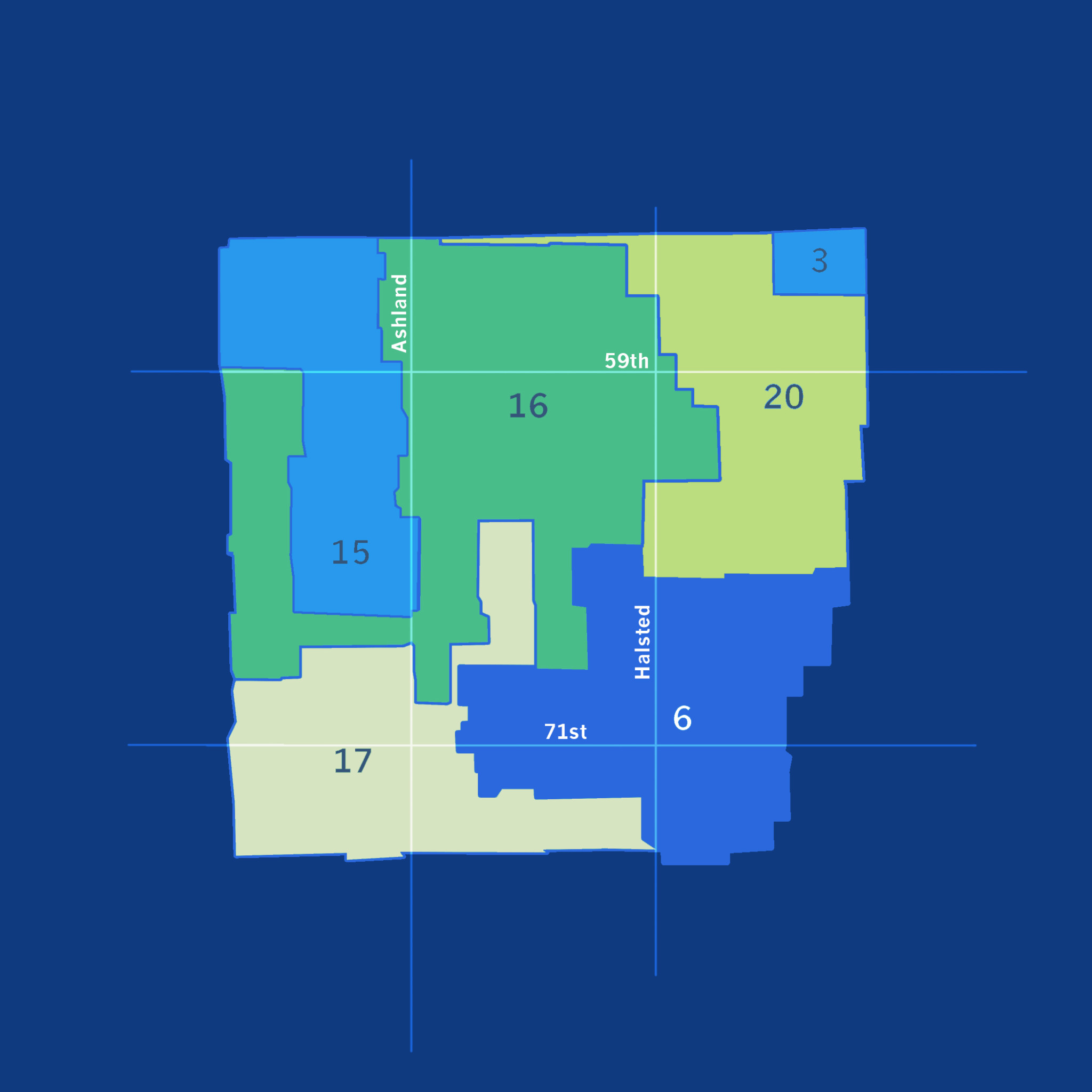

Until city mapmakers decide to draw lines according to communities, and not to play “racial arithmetic,” as Rodríguez-Muñiz phrased it in his study of the 2010 remap process, neighborhoods that are represented by multiple aldermen like Little Village, Belmont-Cragin, and Englewood will have to continue to find ways to overcome the political fragmentation that often prevents projects from moving forward and can contribute to increased violence, according to neighborhood advocates and researchers. University of Chicago sociologist Robert Vargas, who runs the school’s Violence, Law, and Politics Lab, found in his 2016 book-length study Wounded City, which considered the ward boundaries of Little Village, that the western portion of the neighborhood—contained within the 22nd Ward—enjoyed more stability and less violence. The eastern portion, split between the 12th, 24th, and 28th wards, lacks “access to the systemic social organization necessary for preventing violence,” he writes.

In a two–part series published last year on the political fragmentation of Greater Englewood, which has been split into five wards since the 1970s, neighborhood advocates interviewed by the Weekly described how needing to coordinate with multiple independent aldermen impacts the neighborhood. “No one really has a clear focus on the development of Englewood,” Residents Association of Greater Englewood president Asiaha Butler told the Weekly for that series. “When you have the luxury of the Obama library and the luxury of a university and the luxury of all this other development in Woodlawn, it’s really easy to forget a community like Englewood.” State Representative Sonya Harper, who ran the nonprofit Grow Greater Englewood before being appointed to her position in 2018, agreed. “When people look at the Englewood community and all the challenges that we deal with and how we’re portrayed on the news media, the one thing that they don’t know is that we’re split up politically and that lends itself to some of the dysfunction that we have. Englewood gets such a bad rap but I believe that that is one of the biggest reasons why.”

To their credit, the five aldermen who represent the neighborhood held a first-ever Greater Englewood town hall meeting in January, and have promised to increase their coordination. But 17th Ward Alderman David Moore saliently pointed out at the meeting, “Aldermen come and go, mayors come and go, but the people will be here. You all need to know your power, and your collective power and how to use it. No elected official is more powerful than you are.” Left unsaid is how the relative political strength of neighborhoods largely contained within one ward—Bridgeport in the 11th, or Chatham in the 6th—has contributed to the increased power residents of those neighborhoods enjoy.

Jim Daley is the Weekly’s politics editor. He last wrote about state grants distributed to boost Census outreach efforts. Sam Stecklow is one of the Weekly’s co-managing editors. He last wrote about the aldermanic response to COVID-19.

Thirty years ago when I was working on redistricting the then President of the state Senate asked what he was going to do with his incumbents when presented with census numbers that dictated increased black and brown representation. That, in a nutshell, is what political redistricting has become: protecting incumbents. The results of the 2020 census will be alarming for Black Chicago due to population loss and potential loss of Black majority wards. The gerrymandering may be as ugly as ever in the next go round.