This story was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism. It was also produced with the support of Blue Shield of California Foundation, working to change the conversation about domestic violence, and The Pivot Fund, investing in journalism by and for marginalized communities.

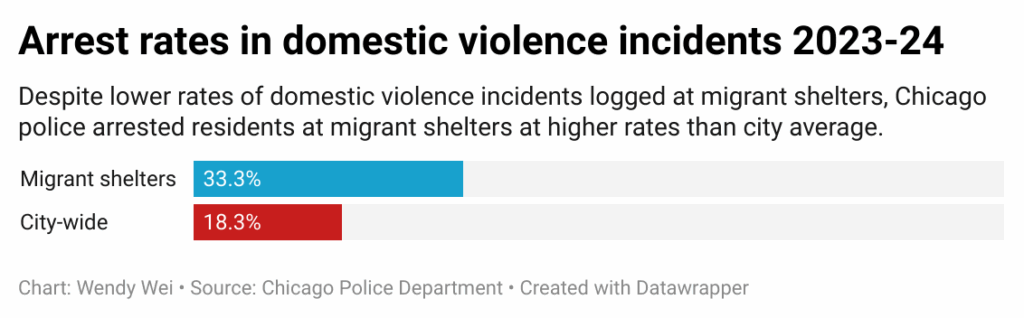

Residents of Chicago’s migrant shelters were arrested more often than average when police responded to domestic violence calls there, despite having a lower rate of incidents than the citywide average. Records reviewed by the Weekly show that in 2023 and 2024, police arrested residents in 33 percent of domestic violence responses at migrant shelters, nearly double the 18 percent arrest rate citywide during the same period. The city has since closed migrant-only shelters, but questions remain about how domestic violence is handled in its new unified shelter system.

Controversial policies at multiple levels contributed to the disparity. Our year-long investigation revealed that conditions in the city’s migrant shelters violated international safety guidelines, and, in a break from state policy, the Chicago Police Department prioritized making an arrest during domestic violence incidents, despite evidence that arrests do not keep survivors safe.

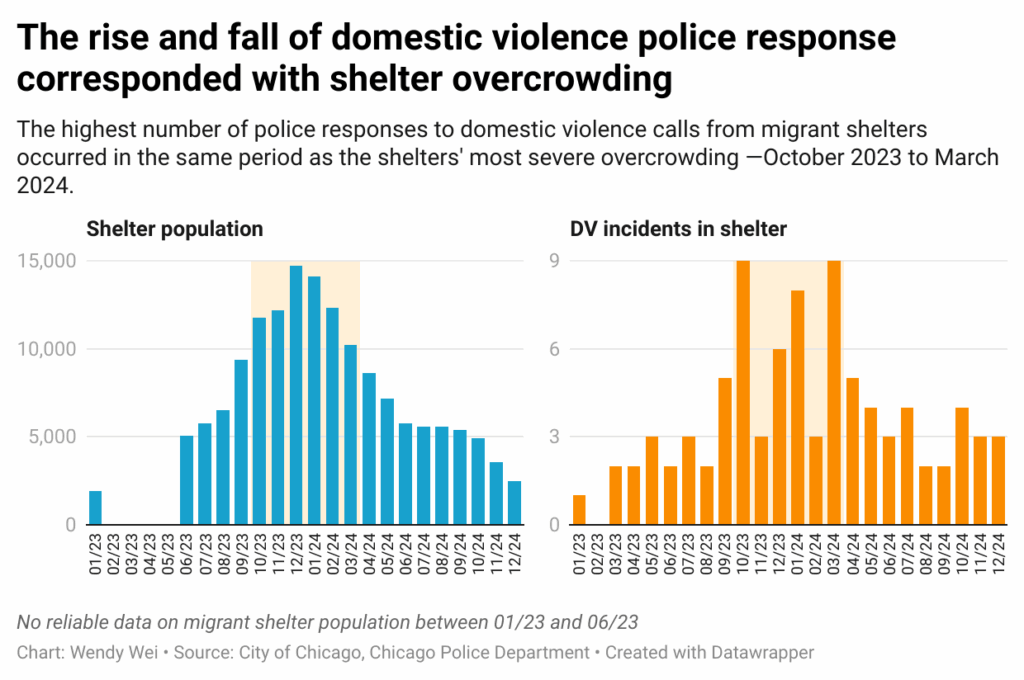

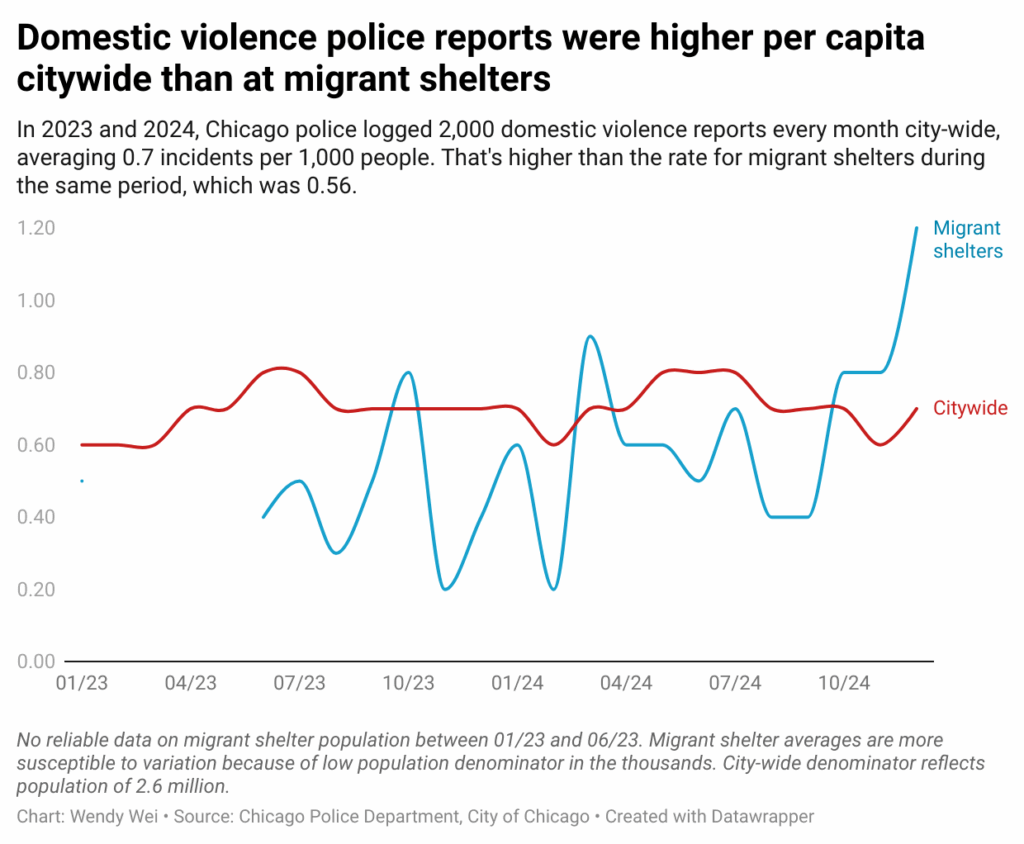

Domestic violence affects one in four women nationwide. Over the past two years, Chicago police responded to an average of 2,000 domestic violence calls every month. Due to the restrictive, crowded nature of the migrant shelters, residents regularly faced violence in them.

Carmen Medina, thirty-six, was barely asleep when her teenage son’s voice woke her in the middle of the night. She blinked her eyes open to the bright overhead lights that illuminated her room at all times. Careful not to disturb her husband, their other two sons, and the four families that shared the room, Medina gingerly got up to accompany her son to the bathroom, which she didn’t feel comfortable letting her children use alone. She didn’t have to worry about accidentally squeaking the door open; they were never closed so security could conduct rounds.

Medina, a Venezuelan mother of three who lived with her husband and family at a city-run shelter in a former Marine Corps building in Albany Park for four months, found it difficult to adjust to the stressful and cramped conditions.

“People were desperate, angry. The children were hungry,” Medina said through a translator. “It was a tragic and surprising experience. We weren’t used to it.”

The food was often bad. People fought frequently in the dining room. There was little reprieve from their crowded, loud environment. Residents’ movements were restricted so that only those with permission could come and go from the shelter with ease. Over the shelters’ two-and-a-half-year run, Borderless Magazine and the Investigative Project on Race and Equity uncovered a pattern of neglected complaints at shelters citywide.

Chicago’s migrant shelters had the kind of conditions that international humanitarian organizations warn will foster violence: overcrowding, lack of privacy, and restrictions on coming and going.

Cynthia Nambo, a community advisor to the City Council on best practices for migrant shelter, said that in such tightly controlled and tense atmospheres, violence was inevitable.

“People are scared, so whenever you’re in a situation [where] people don’t have resources and they don’t have their own space, [violence] will occur,” said Nambo, drawing from her work as a security advisor at volunteer-run shelter Todo Para Todos.

International humanitarian organizations have grappled with domestic violence in refugee settings for decades. Since 1991, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has issued guidelines on preventing gender-based violence, of which domestic violence is a form, in camp settings.

Many of the recommendations are specific: Mixed-sex family shelters should provide designated spaces exclusively for women and children, ensure adequate private space for families, maintain proper lighting in shower areas, and employ staff trained in gender-based violence prevention and response. The UNHCR notes that overcrowding can exacerbate tensions and contribute to domestic violence.

Chicago’s migrant shelters failed to meet several of these basic standards, especially those related to overcrowding and lack of privacy for families.

Physical and verbal fights between couples were common, Medina said. Though she’d never witnessed it herself, Medina heard many stories where a couple’s fight would end in police taking one of them away.

According to records obtained by the Weekly, at least ninety incidents of intimate partner violence were reported to police at city and state-run migrant shelters between August 2022 and December 2024. Most resulted in no prosecution, often because the survivor refused to press charges. However, a third did result in an arrest. Citywide, fewer than one in five calls resulted in an arrest.

Domestic violence survivors face unique challenges when interacting with law enforcement that differ from other crimes. Survivors often maintain economic and familial ties to their abusers. In many cases, they do not want their partners arrested. They just want the violence to stop.

Leigh Goodmark, the Marjorie Cook Professor of Law at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law, is the author of Decriminalizing Domestic Violence. “We have this picture of safety that says, once we make this arrest, the survivor is safe, and that’s just not true,” Goodmark said at a virtual symposium on domestic violence in September. Incarceration can worsen factors that contribute to abuse; the arrested person may lose a job or access to housing.

Couples living with high financial strain have a higher rate of intimate partner violence compared to those with low financial strain, a rate that some studies pin at three times more.

“So, the thing that we’re doing to intervene is actually going to create the conditions in which violence flourishes down the line,” Goodmark said.

The elevated arrest rates at city shelters reflected federal policy on how police should respond to domestic violence calls, yet broke from the Illinois Domestic Violence Act (IDVA) language that advocates for discretionary arrest.

The Weekly obtained eight versions of policy manuals distributed to shelter staff by the Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS) between August 2023 and July 2024. The documents show that while domestic violence procedures became more detailed, critical gaps remained.

What endured was the reliance on law enforcement to end domestic disputes. The manuals all required shelter staff to call 911 when violence occurred.

Before the 1990s, the criminal justice system considered domestic violence a private matter that should be settled between the couple. The 1994 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) required police to make an arrest whenever they had probable cause to do so in a case involving domestic violence, in what is known as “mandatory arrest.” As a result, arrest rates for domestic violence more than doubled in the decades that followed its passage.

“We don’t do that in any other kind of case; in no other matter do we say, police, you must make an arrest,” Goodmark said. Later iterations of VAWA in 2005 and 2013 softened the language to “preferred arrest,” which means arrest is encouraged but not mandatory. The Illinois Domestic Violence Act specifies that arrest is discretionary, leaving it up to officers to respond to domestic violence incidents as they deem appropriate and granting more autonomy to survivors to advocate for or against the arrest of their abuser.

“The preferred response of the officer is the arrest of the offender,” reads a CPD policy directive on domestic violence calls. “Although the IDVA does not have a mandatory arrest provision, officers are required to use all reasonable means to prevent further abuse…including arresting the offender when probable cause exists.”

For immigrant survivors of domestic violence, the stakes are heightened during encounters with law enforcement. Families navigate an immigration system where any police contact can trigger deportation—potentially for the entire family—or lead to family separations.

Fifty out of the ninety domestic violence reports we reviewed involved partners who had children living with them at the shelter.

“A lot of migrants do depend on their partner for stability, whether it’s financial or emotional stability,” said Joel Rivas, a court advocacy supervisor at Mujeres Latinas en Acción. “They do not want to jeopardize having the other person be arrested or deported for those reasons.”

For undocumented people in mixed-status relationships, domestic violence often involves additional forms of control beyond physical abuse. “It’s very common for abusers to weaponize immigration status and threaten law enforcement contact,” said Anna Hori, a research assistant at the University of Chicago Law School’s Immigrants’ Rights Clinic. “This is a major reason victims don’t come forward.”

Rivas has supported about twenty domestic-violence survivors from migrant shelters over the past two years. None had initially sought police help. While police reports capture cases where law enforcement was contacted, many survivors seek help through hospitals, domestic violence hotlines, and community organizations—pathways that don’t appear in police data. The documented incidents likely undercount actual occurrences of domestic violence in shelters.

The police records from the shelters were a mix of self-reports and reporting on behalf of the survivor by shelter staff or a fellow resident.

Despite the difficult living conditions, Medina said staff’s actions were appropriate. “They did a great job,” she said. “They tried their best and were attentive to the migrants who were not breaking rules.”

Police were often ill-equipped to serve survivors’ needs, according to Rivas. “The language barrier is probably the biggest challenge when communicating with law enforcement for Spanish-speaking migrants,” he said. “It’s common for participants to say that when they call the police, the first responders don’t speak Spanish.”

The couple in their late twenties arrived in Chicago together from Venezuela. For months, they lived with more than 200 other recent arrivals in the volunteer-run shelter Todo Para Todos, where they developed a reputation for having belligerent fights on a regular basis.

Despite multiple altercations, the woman never left her partner, and even helped him sneak back into the shelter after he was banned. But things escalated one afternoon in June 2023. What started as a disagreement grew louder, voices reverberating across their shelter’s common area. Residents had grown used to their arguments, but this time drinking glasses went flying, accidentally nicking a bystander.

By the time Nambo, the shelter’s security lead, arrived, other residents had stepped in, physically separating the pair. A few escorted the man outside to talk him down. The atmosphere remained tense as families with young children watched nervously.

No one called the police.

“We see police as responders of acute situations, and to prevent death or physical harm that could be damaging for a long time,” said Nambo, drawing on her experience as a principal at an alternative high school. Instead, volunteers at Todo Para Todos relied on community intervention to prevent violence from escalating to that point.

“There’s a power dynamic when we’re from the country, we know English, we know the systems, and our participants don’t know that,” said a volunteer who witnessed multiple domestic violence incidents at the shelter.

Central to the model was respecting survivor autonomy, even when volunteers disagreed with their decisions. “We cannot force her to be separate from him,” Nambo said.

The man returned to the shelter with the help of other residents several days after his ban. This time, things got really out of control. According to police reports and volunteer witness accounts, he hit his girlfriend in the face—an acute situation that rose to the point where police were called. The incident would eventually appear in CPD records in August 2023.

Todo Para Todos closed in September 2023.

Volunteers eventually found apartments for more than 260 people, including the couple. They do not know the whereabouts of the couple today. According to one volunteer, they eventually separated.

Chicago’s migrant shelter system closed in December 2024. The CPD’s domestic violence arrest policy remains. National policies under VAWA continue to tie essential community response funding to mandatory or preferred arrest approaches, despite research showing these policies may exacerbate the very problems they aim to solve. States receiving VAWA funds must allocate at least 25 percent for law enforcement and 25 percent for prosecutors.

In 2023, $3.4 million of Illinois’s federal funding for domestic violence prevention went to law enforcement and courts while $1.7 million went to survivors services.

Under President Donald Trump’s second administration, even these resources are in jeopardy, especially for migrant survivors of domestic violence. One of the first executive orders Trump signed prevents federal funds from being used for “illegal DEI,” which will make it more difficult for organizations that focus on immigrant populations, like Mujeres Latinas en Acción, to apply for grants. The National Domestic Violence Hotline removed migration-specific services and data this year.

In September, ICE detained two individuals outside Cook County’s domestic violence court, reinforcing concerns that seeking help might trigger immigration enforcement. Further, The 19th reported a significant decline from January to March in new applications for the U visa—the specific visa meant to encourage survivors of domestic violence and other serious crimes to come forward by easing their fears of being deported. Advocates say this reflects fear of deportation among those registered with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services agency.

Local funding is also taking a hit. Mayor Brandon Johnson’s proposed 2026 city budget includes a 43 percent cut in funding for gender-based violence survivors and service providers, according to The Network, a survivor advocacy organization. The Mayor’s Office disputed that, saying the 43 percent figure was not accurate.

Chicago’s new One System Initiative, which merged migrant and homeless shelters in January, has capacity for 7,400 beds—asylum seekers alongside other vulnerable residents across five locations. The Weekly found four additional domestic violence reports in the first months of 2025 involving residents of both foreign and American backgrounds.

City officials did not respond to requests for comment about whether training protocols have changed or what steps are being taken to address the policy gaps that led to higher arrest rates in the migrant shelter system.

“We need to de-emphasize the criminal system’s response to intimate partner violence, and we should look at it as an economic problem, as a public health problem, as a community problem,” Goodmark said. “As a human rights problem.”

Wendy Wei is an independent journalist and audio producer covering migration and interracial solidarity. She is the Investigative Project on Race & Equity’s training coordinator.