On Sunday, March 16, Jake Austen promised his fans that he would be staging “Chic-A-Go-Go’s” “weirdest taping ever.” This was a big promise to make for the long-running Chicago Access Network Television show, which is known for inviting fringe musicians to lip-synch and perform live in front of dancing, costumed “children of all ages.” Nonetheless, few were prepared for that Sunday’s scene, which had the “Chic-A-Go-Go” “kids”—whose ages range from five to fifty—boogie in floral- and animal-print pajamas. In their midst was Art Paul Schlosser, the legendary Madison, Wisconsin street musician; behind them, a green screen was calibrated to display various low-budget special effects and arrays of stars, planets, and galaxies. Schlosser performed his songs—“Purple Bananas on the Moon” and “Have A Peanut Butter Sandwich,” among others—in his usual spare, deadpan style, the same style he used to perform “Scott Walker Loves You” in front of the Wisconsin State Capitol during the state’s 2011 protests. On-screen, the cosmos appeared and disappeared behind the cap of Schlosser’s fluorescent beanie and orange kazoo.

Outside of view, Austen moved in a flurry, rushing back and forth from camera to television to stage as his mane of curly gray hair flew behind him. In addition to his technical duties, Austen is also part of the show’s entertainment act. Donning a sock puppet, he switched into the character of Ratso, the show’s rodential host and lead interviewer. The voice Austen uses for Ratso is a raspy falsetto, making him sound something like a helium-huffing Marge Simpson. When he announced that kids would have a chance to take their picture with Ratso, he was swarmed by children of all ages.

To those who weren’t familiar with “Chic-A-Go-Go,” or who didn’t know Jake Austen’s work, the taping may have come off as an exercise in kitsch, reveling in the haphazard, lo-fi aesthetics of local-access programming. More than green-screen pyrotechnics, however, the show has a core of sincerity, knowledge, and love—one that’s earned “Chica-A-Go-Go” a committed cult following.

“There’s a deeper reality behind that show,” says Barbara Popovic, executive director of CAN TV. “Jake brings in this vast knowledge of music and gives it back. He brings people together who might not otherwise socialize in this city and gives them a chance to all dance and have fun together. For me, it embodies the best values of public television.”

Part of Austen’s deep knowledge of, and commitment to, communal media comes from his childhood on the South Side. A long-time resident of South Shore and a prominent figure in Hyde Park, Austen says he became entranced at a young age by the music he heard growing up in South Shore.

“One of my favorite things I loved about growing up on the South Side was that you would go to a kid’s birthday party, and it would turn out that the kid’s dad or something was in the AACM [Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians], or Oscar Brown Jr. would be there performing ‘Signifyin’ Monkey’ for the kids. I always thought that was great.”

Austen would continue to form relationships with local musicians—including his Kenwood Academy classmate R. Kelly—throughout his career. Aside from a few years when he left Chicago to study painting at Rhode Island School of Design, he has lived on the South Side his whole life. “You want to be around people you know,” he says.

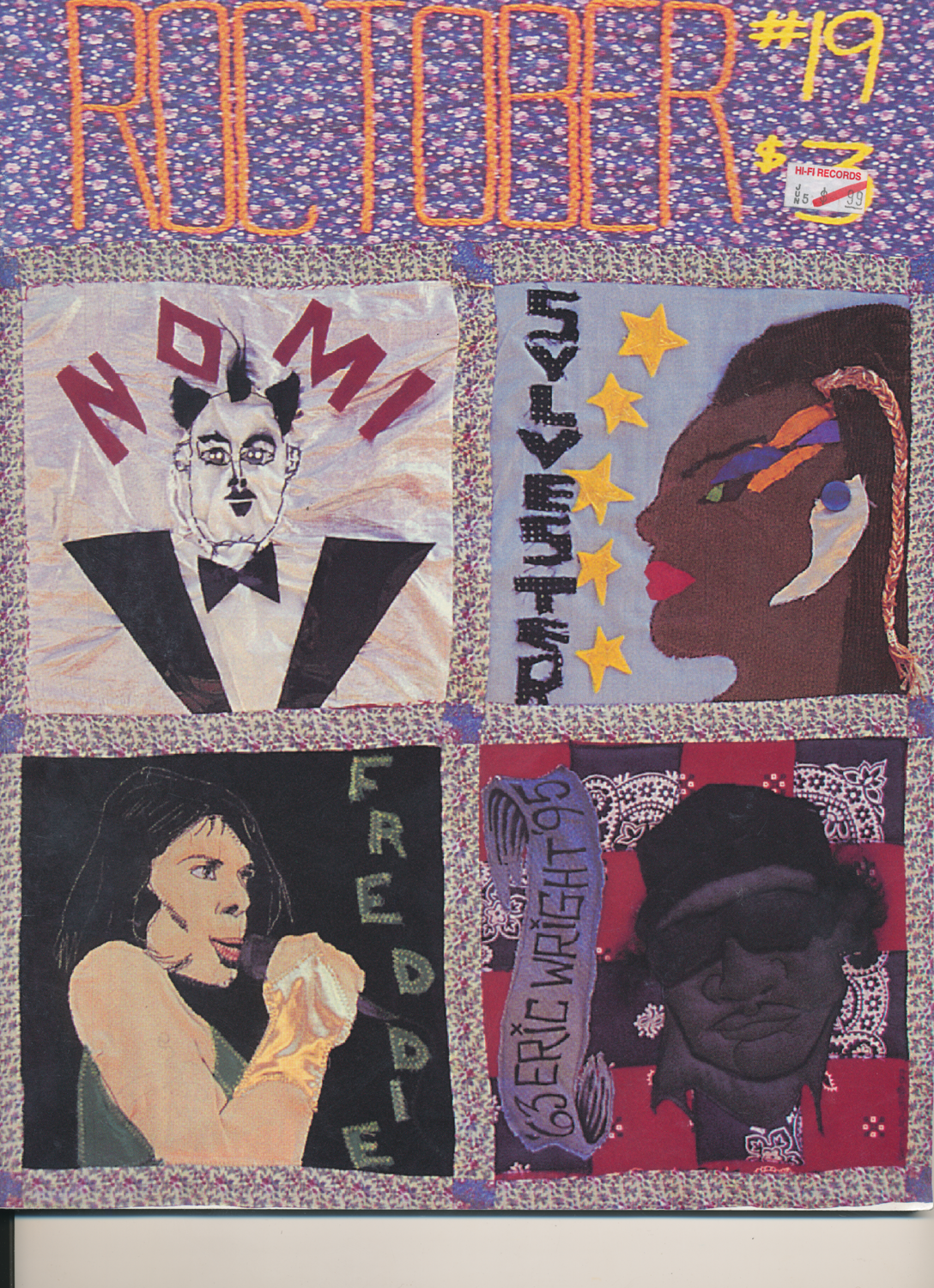

When he returned from art school, Austen began organizing and working with a tight-knit network of fellow music obsessives. One result of this network was Roctober, a music zine Austen founded in 1992 that publishes interviews, reviews, and stories on “unjustly obscure musical heroes.” Roctober publishes local music writers, but it has also attracted some international figures who share Austen’s taste for weird music and cartoon aesthetics. One such collaborator was Nardwuar the Human Serviette, a Canadian radio host who has become an Internet sensation for his eccentric mannerisms and exhaustively-researched interviews with rappers. “Nardwuar calls me for questions for almost every interview he does,” says Austen, “and we still feature Nardwuar in just about every issue of Roctober, so it’s a mutual thing.”

Yet while Nardwuar has developed his personal brand by embracing the Internet and viral sharing, Austen’s career is still very much based in local media outlets like CAN TV and WHPK, where he serves as the station’s talk-radio format chief. “Chic-A-Go-Go” in particular developed out of his deep love for local Chicago television, particularly the city’s old dance music programs. “Dance music television is one of my favorite things you can do with television,” says Austen, “because it’s one of the simplest: you just point a camera at people and watch them move around. But it’s also one of the most compelling: there are narratives you can make up about the dancers you know, and there is so much cultural weight to how different people dance, and so much joy in seeing a little kid who can do a dance.” Austen’s interest in dance television peaked when he was sent out to do photographs for a story on “Kiddie a-Go-Go,” a WCIU children’s dance show that was later replaced by “Soul Train,” a soul dance show that became nationally known, in the early seventies.

After doing some research, Austen and his wife, University of Chicago media studies professor Jacqueline Stewart, decided they would create a new show as a tribute to the old classics. “Jackie and I had always wanted to do something on local-access cable and were always really interested in grassroots and independent media.” Recounts Austen, “We met with Kelly Kuvo from The Scissor Girls, who in the nineties were a pretty dynamic Chicago band. Kelly was one of the really great eccentric artists on local access. She helped us get started.” With Kuvo’s help, CAN TV provided him with training in production equipment and gave him a time slot where he could broadcast his show. It premiered in May 1996, and has aired on a regular basis ever since.

Aesthetically, “Chic-A-Go-Go” evolved by merging the old-school cool of “Soul Train” with Austen’s own cartoon style, which he developed through Roctober. Ratso was lifted directly from Austen’s “Punk’nhead” comic strip, which first appeared in the zine. Initially, the rat puppet was joined on stage by the comic’s titular character, a skateboarding teen rebel with a jack-o’-lantern for a face. After a few episodes, though, Austen decided that having two cartoon puppets was “just too much. It didn’t work. Something was off and we knew we needed a human host.”

Austen turned to his friend Mia Park. She had been a drummer in various bands—Police Car, Hoo Doo Hoedown, and Lobstar, among others—and knew of Austen through the Chicago music scene. “I was just invited to come on the set,” she remembers, “and Jake comes up to me and says, ‘Are you a professional actress?’ I said no. Then he just says, ‘Good. We don’t want professional actors.’ Then after that, someone came up to me with a box of sequins and some safety pins and said, ‘Here, help put this stuff up.’ And that was it. I was never officially hired or anything, but I’ve been doing it ever since, for fourteen years, and I absolutely love it.”

Now in its eighteenth year, “Chic-A-Go-Go” has become one of CAN TV’s most popular entertainment shows. Much of its success is due to the chemistry between the ebullient “Miss Mia” and the cartoonishly sardonic Ratso. Yet the power of individual episodes often comes from how well the musical guest meshes with the absurd, gleeful energy of the show itself. “It usually works because the artists know what they’re getting into. You can’t really volunteer to lip-synch on a show with dancing children and not know what you’re getting yourself into.”

The show’s best episodes are unlike anything else on television. Nobunny, the rabbit-masked garage rocker, proved to be a natural fit for the show when he performed in 2005 using a carrot-shaped mic. An intricately choreographed dance routine by OK Go, which the band members acted out while Ira Glass and other WBEZ DJs pretended to play the instruments, wowed the CAN TV crowd. As Austen tells it, OK Go’s routine “was so charming they got invited on Glass’s ‘This American Life’ tour, which in turn helped them get signed to Capitol Records, and when they were about to get dropped by Capitol Records, they recreated that routine with that treadmill dance video that went viral online. If we hadn’t gotten OK Go to do this silly little dance, they might have never become big.”

Even when the show seems to go off the rails, it’s often too captivating not to watch. Once, after interviewing members of the experimental post-rock band Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Austen decided to play one of the group’s most droning tracks as a dance number for the “Chic-A-Go-Go” kids. The studio quickly turned into the set of a Lynchian zombie film, with children performing slow-motion prowls across the set. Another time, Austen invited AACM co-founder Phil Cohran to the studio and asked him if he could play a particular song. “He looked at me and said, ‘You know that’s in like 16/83 time or something. You can’t dance to that. And we said, ‘Just don’t worry about it.’ They love dancing to anything. They’ll always try.”

Ratso’s interviews often provoke surprisingly candid moments from guests. The squeaky-voiced Detroit rapper Danny Brown seemed so at ease when chatting to Austen’s sock puppet in 2012 that it was easy to wish Brown was a co-host of the show. Still, Miss Mia says that it was Andrew W.K., the party rocker and motivational speaker, who had the best “human–puppet interaction skills I’ve ever seen. He was so sweet and comfortable, even with the littlest Ratso.”

Often, though, the more obscure performers are the ones who really invest a serious sense of meaning in the show. “My favorite guest was this guy Alan Gilette,” says Park. “He’s this very peculiar character from Peoria who does karaoke versions of pop songs. He takes himself very, very seriously but he wears this huge cowboy hat, and it’s hard for some people to keep a straight face around him. But we took him very seriously and were very respectful. Then, when I asked him about why he [wears the hat], he went into this long, amazing answer about the meaning of his work, which you would never expect. I think that’s part of the beauty of the show, that you can get a response like that when you would least expect it.”

For Park, whose “Chic-A-Go-Go” position has been the most stable part of her varied career (drummer and musician, critic, part-time actress, yoga instructor), the show is ultimately motivated by joy. “None of us get paid. It’s all completely voluntary. We just get to facilitate joy. Unfiltered, pure joy.”

Despite the joy of the show and its volunteer staff, there are fears that “Chic-A-Go-Go” and many of the other CAN TV programs may be in jeopardy.

A city contract with Comcast, the cable company, is currently up for a ten-year renewal. Comcast has one of three cable franchise agreements with the city. (The other two are held by RCN and WideOpenWest.) The sticking point in negotiations between cable providers and the city is often public-access television, which is rarely profitable for cable companies. So far, Comcast has been hesitant to pledge its full, continued support for CAN TV. Instead, the company has opted for a three-month extension, which began in March, on its negotiations with the City Council’s Committee on Finance, with an option for an additional three months to be granted at the discretion of the city’s Department of Business Affairs & Consumer Protection. As a result of the extension, the financial future of CAN TV remains unclear. Austen suspects that Comcast may be buying time to lobby the city in an attempt to downgrade its funding commitment to public access. (A spokesperson for the company declined to comment on its negotiations with the city.)

According to Barbara Popovic, if Comcast downgrades their funding agreement the station will also receive significantly less funding from RCN, a smaller provider. The contract between RCN and the city, which was negotiated in 2012, includes a “most favored nation” clause that guarantees the company will provide no more public-access funding than Comcast does. “If both Comcast and RCN downgraded their funding agreements,” says Popovic, “seventy-five percent of our operating budget would be affected.”

The suspicion that Comcast may downgrade its support is not without precedent. In 2009, legislation in California allowed Time Warner to cut its funding to Los Angeles’s fourteen public-access stations. (Time Warner is in the process of merging with Comcast.)

“We don’t want to become California,” Austen says. With Gordon Quinn, artistic director of Chicago documentary studio Kartemquin Films, and a few other dedicated activists, Austen has formed the Committee for Media Access. The group is organizing a call-in campaign to bolster public-access support from aldermen.

Austen insists that for Comcast, the issue is “not a lack of money” (by revenue, Comcast is the largest communications company in the world). Productions costs are low, and Austen and other CAN TV producers are not paid. “They just don’t want to have this extra stipulation to provide us with funding,” he says.

“Any time local access is under threat, we share that threat,” says Park. “If CAN TV lost its funding, our show would probably continue somehow, but it wouldn’t be the same”

Austen is not unaware of financial pressures. He makes part of his living as a freelance music journalist, working for publications such as the Reader and Cleveland-based Belt Magazine, but finds, not surprisingly, that his time-intensive research process does not always receive ideal compensation. His three books—one on televised music programs, one collecting his interviews with obscure rock and soul stars, one on the history of minstrel figures in music—have not sold well, he says. He hopes to be able to sell his new book project, a chronicle of The Jackson 5’s time on the South Side, but has had trouble finding a publisher. Roctober has also had to cut its subscription services due to high shipping costs. Austen even worries that his now-famous friend Nardwuar—whose show is currently produced by Pharrell Williams’s I Am Other collective—“hasn’t really figured out how to make money from what he’s doing.”

But for Austen, Park, Stewart, and the rest of the “Chic-A-Go-Go” crew, the show is one thing in their lives that doesn’t revolve around money. “It’s rare in life that you just get to be completely who you are” says Park, “but on ‘Chic-A-Go-Go,’ you can.”

An inspiring and thoughtful article.